Looking through my parents’ storage boxes, I found letters that my mother and father sent one another prior to my existence. This unfathomable world was decades away from mobile phones, public internet connectivity, and social networking. Along with explanations of humorous or ordinary everyday episodes and proclamations of love, the letters included doodles, crossed out words, and long postscriptums. I don’t know if my mother or father ever dabbed some perfume on their letters hoping to evoke butterflies in the other’s stomach; it would not have been out of place.

My parents may not have thought about it, but their craftsmanship likely had an impact on the recipient. Perhaps my dad’s use of smiley faces (predating by 45 years when the word “emoji” was selected as Oxford Dictionary’s Word of the Year) made my mom smile. Maybe crooked handwriting or spelling mistakes hinted that one of them was anxious or hurried. The intuitive idea that the recipient of a letter responds not just to the dictionary meaning of the words within but also to the tone, paper, calligraphy, neatness, and presentation would be wrapped up by the behavioral science concept that “context matters.” When my parents customized their letters they were in control of said context. They manipulated the context to amplify their love or neutralize a piece of sad news.

Things done changed

Technology has created new ways for people to interact. Email and instant messaging, coupled with smartphones and a widely available Internet have created a different set of expectations in terms of expediency of messaging (now), allowed us to reach people in far away places and made it possible to reach people we wouldn’t have been able to reach a lifetime ago (e.g. Amazon’s boss: jeff@amazon.com).

Technology greatly expanded my range of possibilities: I can send audio snippets, hilarious gifs, and memes that serve as an allegory to what is being discussed. However, although it created new roads, technology also standardized the vehicles. When I use a messaging app on my phone, there is only so much I can customize. Writing my wife, I can include emojis and perhaps create my own emoji footprint through re-using particular chosen graphics ![]() . But the range of interactions is preplanned. My font choice doesn’t provide clues about my mental state. I can’t spray my cologne or slip an origami animal into my instant message. Does context still matter in modern social media communications? In other words, could my use of one social network over another signal something about me or cause a message I send to be understood through a different emotional filter?

. But the range of interactions is preplanned. My font choice doesn’t provide clues about my mental state. I can’t spray my cologne or slip an origami animal into my instant message. Does context still matter in modern social media communications? In other words, could my use of one social network over another signal something about me or cause a message I send to be understood through a different emotional filter?

Context still matters

Even though we typically use a set of comparable social network channels to communicate with others, my research hypothesis was that context still matters and that social media channels themselves do affect how our words are received. I anticipated that the same messages would not resonate in the same manner whether they were sent and received in Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, or WhatsApp. I wanted to prove that social network users were likely to implicitly judge content differently in the context of what a social network typically provides – whether it is professional services (e.g. LinkedIn) or more general interactions with friends and acquaintances (e.g. Facebook).

If proven true, the implications from this research would suggest that certain types of content are a better fit for some social media networks versus others. Marketers often use the same media campaigns across channels but maybe more thought should be given to ensure the content is not incongruous with the context. Perhaps, BeLinked, a dating app that suggests matches based on LinkedIn profiles, has a fundamental flaw in that the professional context elicits a negative reaction that is not present for other social networks.

Designing the research experiment

The study, conducted as part of my behavioral science masters at the London School of Economics aimed to quantify the impact of the “container” on the message through various typical social interactions. It was carried out through an online experiment. Participants were asked a series of demographic and social media usage questions and were then randomly allocated to four interactions within one social media channel: receiving a request to connect, receiving a text message, receiving a picture, and receiving a like.

The study also had a control condition that did not specify a social network or messaging app. Instead, it asked respondents to, e.g. “imagine they received a social network request to connect” or “imagine they received a ‘like’.” The fictional correspondence across all networks was with an androgynous individual, Sam, whose gender was not specified and whose picture was not distinctly male nor female. After seeing a visual mockup of each interaction, participants were asked to rate how connected they feel with Sam following the interaction. Once the four interactions were complete, respondents were asked how confident they are they will “remain in touch.”

The chosen social network tools (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and LinkedIn) all allow for building and maintaining social connections, albeit with slightly different target markets and providing for distinct functionalities. Whereas Facebook and WhatsApp are for general connectivity, Instagram specializes in sharing pictures and video, and LinkedIn is intended for the business community.

However, even with differing specialized features, all these platforms have a core suite of capabilities that are interchangeable such as accepting connection requests and sharing content. All of the selected social media tools have a mobile app offer which means that they can all be used for immediate communication on the go. Although social media networks nowadays allow for a much wider range of interactions (e.g. sending video content, applying a funny filter mask to one’s picture, sending stories that expire), the interactions studied are relatively standard and are present across all the social networks (the exception is “liking,” which is not present in WhatsApp).

Study image bank

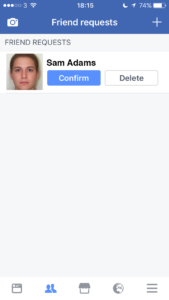

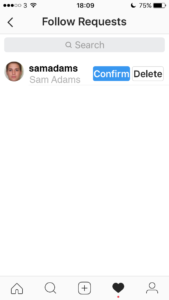

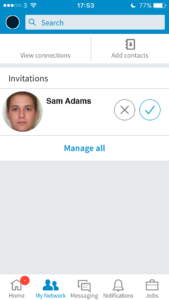

Condition: Friend request

Control: Imagine you received a social network request to connect from an acquaintance (“Sam Adams”). Assuming you accept the request, would you feel more connected with Sam following this interaction?

|

|

|

|

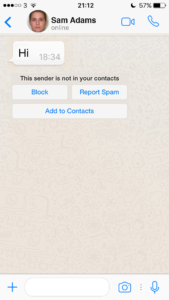

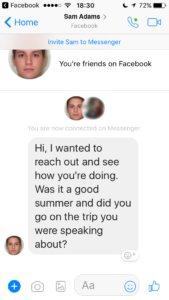

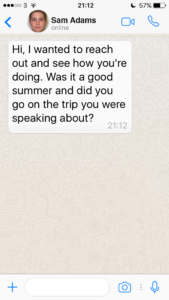

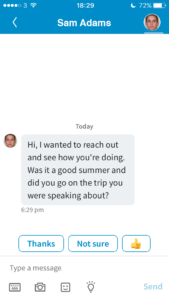

Condition: Text message

Control: Imagine you received the following message from Sam over social media: “Hi, I wanted to reach out and see how you’re doing. Was it a good summer and did you go on the trip you were speaking about?”. (…)

|

|

|

|

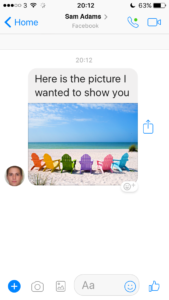

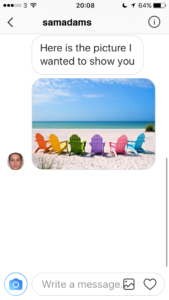

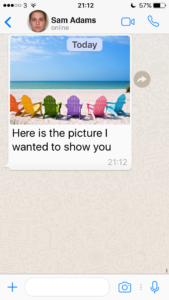

Condition: Picture message

Control: Imagine Sam sent you a picture of the beach over social media. Would you feel more connected with Sam following this interaction?

|

|

|

|

Condition: Like

Control: Imagine Sam “liked” one of your posts on social media. Would you feel more connected with Sam following this interaction?

|

|

NA – WhatsApp does not have a like notification |  |

Making sense of the data

When it came to the data analysis, I narrowed the analysis to the 570 respondents who self-reported themselves as having experience across all the social media channels I was investigating. I controlled for demographic data and used techniques appropriate for ordered and categorical dependent variables. I ran a model for each interaction and found that all of the models had valid explanatory power (95% confidence interval).

This results showed that the communication “wrapper” had an impact on the message being transmitted. The same content and online interactions yielded statistically significant different reactions from study participants across networks. LinkedIn consistently resulted in lower feelings of connectedness when subjects were asked to score receiving a friend request, text messages, and a “like”, i.e. on three of the four interactions I measured. LinkedIn was also rated statistically lower in terms of the likelihood to remain in touch. These results could be due to generally lower feelings towards LinkedIn or a mismatch between LinkedIn and the more casual, not work related, interactions carried out in this research.

On the other hand, Facebook and Instagram revealed higher ratings of connectedness following receiving a message with a picture, even when the image was relatively generic and impersonal. It is easy to hypothesize that Instagram, being a visual medium-focused network, is especially conducive to pictures eliciting feelings of connectedness. Even though Facebook is less reliant on just visual content, picture images are evidently congruent in this channel.

A summary of my findings is as follows:

| Model | Findings |

| Friend request | A friend request on LinkedIn and WhatsApp was linked with lower ratings of connectedness |

| Text message | A text message on LinkedIn resulted in lower ratings of connectedness |

| Picture message | A picture message on Facebook and Instagram resulted in higher ratings of connectedness |

| Like | A like on LinkedIn resulted in lower ratings of connectedness |

| Likelihood to remain in touch | LinkedIn had a statistically significant lower likelihood to remain in touch |

This research makes the case that each social media network has a persona, and the interactions carried out in the network should fit its persona.

Incongruent content to channel pairings (e.g. posting one’s CV to Facebook) are likely to be noticed as such. We should observe some channel etiquette! If we meet someone in the professional sphere and have them as a LinkedIn contact, we probably shouldn’t send them lasagna recipes through LinkedIn (unless we are OK with being perceived as a monster). If we eventually would like to discuss more personal matters with them online it would be beneficial to do through another network: once a work colleague graduates from being a LinkedIn work contact to a “friend,” the research indicates they should be added as a friend on something like Facebook, where the type of communication we would like to have with them will better fit the context it is in. Using LinkedIn in the same way as Facebook—such as sharing personal life anecdotes or entertaining links—is likely to result in that content being viewed less favorably than had it been shared on a social network channel more oriented to everyday life.

There are also some implications for the social networks themselves. Aside from trying to be the Swiss army knife of social networks, another social network ambition is to become an ecosystem, a base layer through which all other online behavior is carried out. Without leaving the app, some social networks let us play games, book appointments, check into flights, reserve taxis, and the like.

However, some functionalities may be a more cohesive fit than others, which may not fit with the “personality” of the social media channel. It will be interesting to monitor these trends over time. Perhaps, as the lines between professional and private lives become more blurred, the effects we are currently seeing will cease to be and LinkedIn will become the place where singles find dates.

Perhaps not.