In the world of user research, no idea is a bad idea.

If you have an idea for a great piece of research, act on it. In fact, your first epiphany is the seed from which all great things will grow. Your idea will eventually shape your hypothesis—your very best idea. This is your proposed explanation based on your current and limited evidence, paving the way from your starting point.

The investigation to follow is where your user research comes in.

For far too long, concepts such as Agile and Minimum Viable Product have been used by companies as a way of accelerating their strategy through design and development process. The problem with such concepts is that they allow a team to collect the maximum amount of validated customer research with the least amount of effort. Simply put, customer insight isn’t established until much later in the research piece, if it all. But, if you’re like me, you’ll fall into the camp that believe that at the heart of each and every methodology is learning. Learning should always involve your users.

Thankfully, the industry as a whole is now taking user research more seriously. Companies such as Amazon, which has had enormous success with its customer-first focus, can attribute their success to this newfound recognition.

Here at Space Between, our team dedicates a lot of time to researching how best to achieve truly unbiased results from our candidates. This was especially so when we first started out. Since then, we have run hundreds of groups and sometimes learned the hard way. Instead of making other potential researchers reinvent the wheel, we’re sharing what we have learned so that others can avoid the pitfalls that we experienced.

In this article, I focus on three areas: candidates, running the session, and post-session.

“The most important single thing is to focus obsessively on the customer. Our goal is to be earth’s most customer-centric company.”

Jeff Bezos, Chief Executive Officer of Amazon

Plan

Let’s start as we mean to go on. I want to outline the three main points of what your strategy should aim to cover before we get to the candidate stuff:

- Objective: What are you hoping to get out of running the user research piece?

- Hypotheses: What do you expect to happen?

- Method: How many people will you need, and what type of research will you run?

Once you have established what it is you hope to achieve from your user research interviews, your starting point and research focus becomes clear. It also helps you define what your measures and outcome applications from the research could be.

Candidates

Count your candidates

A common question for newbies in user research is “how many candidates should we use?” And the answer is, it depends.

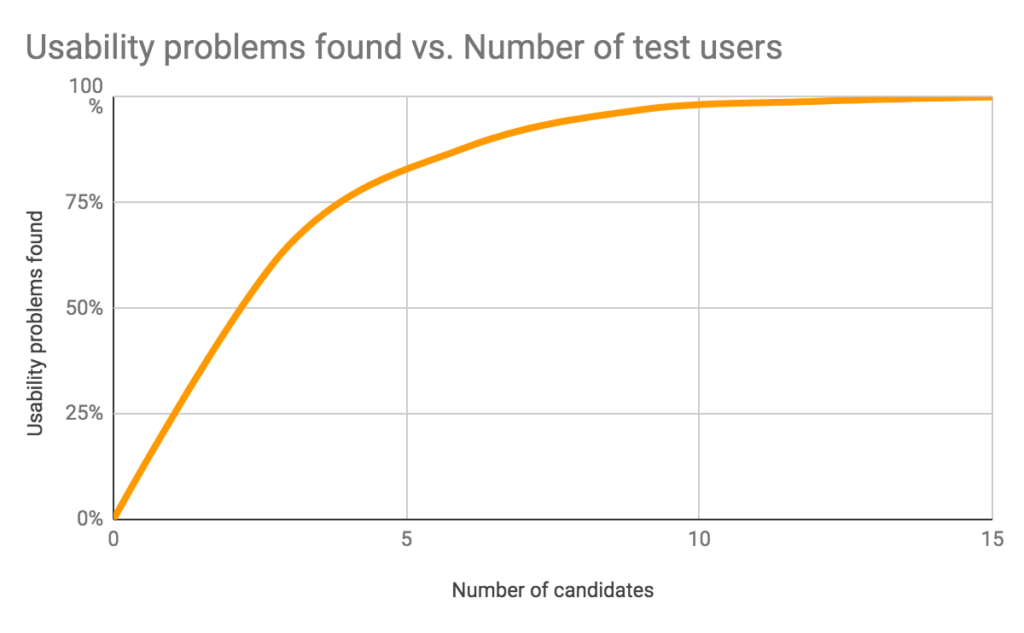

Jakob Nielsen argues that “the best results come from testing no more than five users and running as many small tests as you can afford.” Although this sample set sounds small, it’s based on finding the majority of issues with the least amount of waste. Nielsen points to the fact that after running five user sessions, you will find 85% of the issues experienced.

The above graph estimates that if we then went on to test 15 users we should be able to uncover 100% of the problems in the design. So, why wouldn’t we just test with 15 candidates from the get-go and be done with it?

The theory behind user research is that we should run tests more frequently, with fewer candidates. We can run more sessions after implementing the improvements we found in all previous testing. It allows us to continually validate customers’ thinking and iterate our previous designs.

The caveat: Nielsen’s study is, unfortunately, outdated, and there hasn’t been much further research on the subject in recent years.

In marketing, we often categorize our customers into user types, known as user personas. Ensure that the candidates you recruit reflect and do not dilute your user personas. To test and compare five different personas, always have the same number of candidates for each character set to ensure equality in diversity.

Another consideration is the return on investment of the overall project. If it is a multi-million-pound rebuild of an existing, already successful product, you’ll have an easier time finding additional candidates that will enable you to get better, more complete data.

Get the correct candidates

We feel that pre-qualifying the quality of the candidates is more important to the study than getting the number of candidates right. Always look to get customers that suit your company brand and who have a genuine interest in the product (while also ensuring a diverse split across your group).

The ideal situation is to get a sample of candidates that represent each of the goals and behaviors being tested. If your personas don’t have a common link, best practice would dictate increasing your sample size to avoid diluting a specific user type.

Some additional considerations include:

- Where do your ideal candidates live, and how can you get to them?

- Do you want your current customers? Or would you have better results looking at people who you’ve not used you before?

- If your customers are high earners, or very specific personas, could you find them at a specific event?

Keep your client anonymous

Unless you’re doing user research on a specific brand, you should try and keep the conduct of your research anonymous. You don’t want your customers’ preconceptions to influence them.

I once ran a user research project for a large, luxury, holiday brand. When looking at the competitor products, candidates made assumptions based on their knowledge of the competitor. Although this outcome was still really interesting—we gained insight into a brand’s core customer set—we also want to build a product that works for people who have zero prior knowledge of the product in question. First-time users are not likely to make such assumptions.

Get a waiver

Law and ethics mandate that you collect a waiver from your candidates before the start of your user research sessions. As a starting point, the waiver needs to cover a few basics:

- Confirmation that you can collect personal data.

- If you’re filming the session, confirmation you’re allowed to film.

- An agreement that the data can be shared with people involved in the project.

- Explanation as to how you intend to protect their privacy.

In addition, you may have other areas to consider that are specific to your research. For example, if you’re comparing your own site to a competitor’s, let the candidates know that their data may be collected by a third party (because you have no control over this data). Allow the candidate to invent data if data is required.

Running the session

Relax your user

If you’ve ever been on the receiving end of user research, you will know that it can be a pretty daunting experience, especially your first time. Some people can feel that they’re the one being tested, not the product or solution. Others don’t want to hurt your feelings, assuming you may have a personal affiliation with the product.

We believe the most important requirement when you first meet a new candidate is to put them at ease as much as possible. Ask their name, what they do, what they’ve been doing in the day, any questions that may help them to relax and break the ice. Get to know them with questions. Ask about hobbies… sports? Do you dance? Do you enjoy music?

A little ice-breaker will allow the candidate to hopefully feel comfortable enough to be able to ignore your presence once the testing has started. Keep in mind that the candidates are in a room, likely with cameras, a two-way mirror, and with somebody they’ve never met. All of this small talk will aid in moving their minds away from that concern and to focus on the task at hand.

As well, inform the candidates that you’re not testing them—you’re testing the prototype. Make them aware that your job is to simply understand it better and to see the prototype through their eyes. Their valuable input helps us to understand how they feel about it and lead to potential improvements. It’s vital to stress again that they themselves are not being tested, and they can’t do anything wrong.

Set a clearly-defined task

The most commonly overlooked part of user research is having a clearly defined task that puts the user in the correct mindset. Simply asking the user to “do something” is not enough.

Let’s take a fast-fashion brand as an example. If the task you describe is to find and purchase a green shirt and jeans, then that is what the user will search for, regardless of their own taste. They’re likely to pick the first one they find, make their purchase, and the task will be completed.

You will achieve better results if the task is defined but not too defined. Keep the task simple, but highlight some key areas for your users. Let’s look at these step-by-step using some examples for you could adopt in this scenario and the effects that each can have.

Task 1. “You’re going on a night out with friends, and you’re looking for a new outfit.”

This phrasing allows customers to get into the mindset of the story. It helps conjure questions: Who they might go out with? What they might do? What will their friends be wearing? But all the time they’re focusing on their own opinion, and they’re not being influenced.

Task 2. “Find something for the evening, say, next Friday.”

This is an important nudge for our user. In this example, you may be curious to understand what the customer thinks about the delivery options available, so you give them something to work toward but without specifically telling them to look into a type of delivery.

Task 3. “Research and purchase something that would be appropriate for you on that night.”

This phrasing reiterates that the decision is down to the candidate’s own taste and gives them the freedom to make their own choice. It also leads them to the final goal of making a purchase.

Task 4. “As you progress through the purchase, speak aloud.”

You want your users to tell you their thoughts as they move through the website, and you want this to be as natural as possible.

Task 5. “If you have any questions, please ask your chaperone.”

You don’t want the user to feel unsure at this point, you want to give them time to feel completely comfortable with the task. Inviting them to ask any additional questions of the team member in the room—and not limiting their questions—will make the candidate feel relaxed in their task.

Speak aloud

Asking your users to speak aloud is not only a cost-effective way to get incredibly valuable insights from your users, but it’s also very powerful when taking these insights back to key stakeholders. Stakeholders can be very quick to dismiss an internal idea, but dismissing ideas is much harder to do when they are watching one of your customers come up with an issue or problem.

The adaptive nature of speak aloud prototyping means that it is also useful to use at any part of the development lifecycle (from very high-level design to very complex prototypes). It is also important to understand some of the downsides that come with the ‘speak aloud’ tool.

Speaking aloud is not a natural environment for your users. Articulating every thought that enters your mind is challenging, especially when learning a new product or user interface at the same time. Even interrupting the candidate’s train of thought (to ask them a question) and allowing them to open up to you in that moment with their thoughts can drastically change the way the user might perform a specific task.

This leads us to the more critical issue with ‘speak aloud’—the ability to add bias to the study. As I mentioned previously, asking questions is often required to encourage a candidate to speak their thoughts. However, asking them the wrong question can influence their performance.

Make sure that your chaperone is aware and capable of managing this issue—‘opening’ conversational doors when required but not influencing the study by doing so. Most critically, if any influence has been given, the data set for that particular contamination should be disregarded.

Avoid influencing the candidate

There is a scientific theory called the observer effect, which introduces the idea that observing a phenomenon can change that phenomenon. This is very true in the case of user research. Not only are we changing the state of play by taking notes, conducting research in an unknown location for the user, using a product your users probably aren’t familiar with, but we’re also in the room with them, observing. All have the potential to influence a candidate.

The observer effect is hard to remove, but it can be mitigated by helping to relax the user prior to testing. Reducing researcher influence, though, is critical for your research. Some of the common pitfalls that even the most experienced user researchers should look out for are:

The observer effect is hard to remove, but it can be mitigated by helping to relax the user prior to testing. Reducing researcher influence, though, is critical for your research. Some of the common pitfalls that even the most experienced user researchers should look out for are:

- Asking leading questions. “I like this. What do you think?”

- Asking a question that changes the user’s behavior. “Let’s go back to that. What do you think?” Try and save these questions until the end of all the required tasks to minimize the potential for observer effects.

- Incorrect task wording (if your task is too linear and doesn’t allow the candidate to think as a real user would).

- Body language (not paying attention or looking frustrated/happy).

- Environmental variables (background noise, temperature, lack of a drink, etc).

One common influencer is feeling the need to fill a pause. Dr. Salma Patel

(user researcher in the Civil Service and associate lecturer at The Open University) says: “Don’t be afraid of pauses. Don’t try to fill them in when the participant goes quiet. Give the participant time to think and hesitate if need be (that may end up being a finding in itself).”

Take notes

Taking notes during the session is incredibly important and will drastically influence your analysis time, but note-taking is only as effective as you make it.

If at all possible, the person who’s sitting with the candidate should not be taking notes. An ideal situation would be that the session is streamed and recorded into a separate room where the note-taker sits. The candidate will feel less anxious about the situation, and observers can talk about the session more freely as it is happening.

The key to good note taking is standardization among everybody involved. We would actively encourage you to supply your team with a template to follow, but more importantly, make sure you’re taking note of facts and not opinions. You want your focus to be on what people are actually doing. What steps are they taking? Do they encounter any issues or likewise? Do they find anything incredibly simple? What emotions are they feeling? Do they mention any frustration, elation, or anything in between?

What goals are they looking to achieve? Do they feel content about the intended goal? At the end of the session, give yourself time to review your notes. If possible, review with the team and candidates. At the very least, have confirmed contact details with which to get in touch after the fact if clarification is required from a candidate after departure.

As hard as it can be to do, restrain yourself and your team from problem solving at this point. It’s easy to move into a mindset of fixing—rather than learning—and this has the potential to bias your future thinking.

Teena Singha, HCM Experience Design Professional, when we asked her for her tips on note-taking, said: “If you have the time, spend 10-15 minutes and jot down or elaborate on the key things you learned immediately after the session. You will be surprised at the accuracy of top-of-mind insights, noted right after the interview. If you wrote a couple of notes in ‘chicken scratch,’ immediately after the session is the best time to elaborate on these ideas, so they are not forgotten. You will find that your high-level notes or a summary of the session can be formulated in that short time frame.”

After the session

Translate your notes

The very first thing you should do after you’ve said farewell to your final candidate is take another look through your notes and work on translating them. You’ll have lots of chicken scratch style notes from the day, some of which you may not have even written yourself if you are conducting your research as part of a team.

Take this from somebody who’s made this mistake: The note you jot down in a flash of “the candidate really liked the first product” will not seem so obvious once you’ve sat through 15 more candidate tests and had two nights sleep! So, this moment is the best time to look through these; you’ll have the best memory of what you meant.

Protect the data

There are two areas to focus on here: keeping hold of your data and candidate privacy.

In keeping hold of your data, back up all assets created from the day… any candidate waivers, videos, audio, notes. Put everything in a secure space online so you don’t lose any data due to corruption, misplacement, or anything else.

Secondly, privacy. The data we collect will more often than not be personal data for your users, which they’ve approved in your waiver. Back up all notes and remove them from personal devices. The proper protection of your data is not only a legal requirement from a data handling point of view, but it will also help you with your upcoming analyses.

Report and distribute

Your job when researching is to help pass as much information and knowledge as possible on to the next stages. As we know, this is often overlooked and under-appreciated.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask, for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.”

Albert Einstein

With the right information, we’re able to solve more challenging problems and are able to be more confident in our choices.

So, you want to make sure that the results are seen and accessible going forward? An easy way to make them seen is to run a ‘wash-up session’ to deliver the results of your research. Include facts about your findings that will allow the team to make better decisions going forward. There is likely to be a lot of energy in this session, and the team should go away feeling incredibly excited to make changes.

But, as with anything, people will start to forget this information. Make sure the results are easily accessible; if the results are where your team can find them, decisions can be made based on the research completed rather than gut feeling. Better decisions will come.

Prove the value

Attributing value back to your research is incredibly important; many people within your company might not understand the work you’ve undertaken or the impact it’s made on the project.

Where possible, try to make sense and define the value you’ve added. If your work is ongoing and a change is made on a live product because of your research, it’s an easier method to measure because you’ll see the difference after the change or after it was tested.

However, prototype researching (and other areas where you’ll impact the final product) can be harder.

“If you think good design is expensive, you should look at the cost of bad design.”

Dr. Ralph Speth, Land Rover

A great way to explain the value of the work you’ve completed is to highlight the number of areas that are different due to your research. Was the product redesigned? Did the goals change? Do the designers and developers keep referring to the research piece you’ve put together? All of these can be seen as a value and a positive impact on the project. Never building something wrong is considerably cheaper than finding something wrong and then correcting it.

Summary

This article isn’t an exhaustive list of tips. It’s my way of sharing some of the more common factors that have come up during my time as a researcher.

If I had to pinpoint the most important takeaway, I’d say it is to watch your own sessions afterwards and look for your own pitfalls. Much like public speaking, we’re looking for the habits that we ultimately want to iron out.

User research isn’t as hard as people may presume it to be, but it can be easy to get wrong. My aim in this article is to help direct you toward better, more fool-proofed research going forward based on my own experience.

Nice work Luke!