The Above-the-Fold Myth

We are all well aware that web design is not an easy task. There are many variables to consider, some of them technical, some of them human. The technical considerations of designing for the web can (and do) change quite regularly, but the human variables change at a slower rate. Sometimes the human variables change at such a slow rate that we have a hard time believing that it happens.

This is happening right now in web design. There is an astonishing amount of disbelief that the users of web pages have learned to scroll and that they do so regularly. Holding on to this disbelief – this myth that users won’t scroll to see anything below the fold – is doing everyone a great disservice, most of all our users.

First, a definition: The word “fold” means a great many things, even within the discipline of design. The most common use of the term “fold” is perhaps used in reference to newspaper layout. Because of the physical dimensions of the printed page of a broadsheet newspaper, it is folded. The first page of a newspaper is where the “big” stories of the issue are because it is the best possible placement. Readers have to flip the paper over (or unfold it) to see what else is in the issue, therefore there is a chance that someone will miss it. In web design, the term “fold” means the line beyond which a user must scroll to see more contents of a page (if it exists) after the page displays within their browser. It is also referred to as a “scroll-line.”

Screen performance data and new research indicate that users will scroll to find information and items below the fold. There are established design best practices to ensure that users recognize when a fold exists and that content extends below it1. Yet during requirements gathering for design projects designers are inundated with requests to cram as much information above the fold as possible, which complicates the information design. Why does the myth continue, when we have documented evidence that the fold really doesn’t matter in certain contexts?

Once upon a time, page-level vertical scrolling was not permitted on AOL. Articles, lists and other content that would have to scroll were presented in scrolling text fields or list boxes, which our users easily used. Our pages, which used proprietary technology, were designed to fit inside a client application, and the strictest of guidelines ensured that the application desktop itself did not scroll. The content pages floated in the center of the application interface and were too far removed from the scrollbar location for users to notice if a scrollbar appeared. Even if the page appeared to be cut off, as current best practices dictate, it proved to be such an unusual experience to our users that they assumed that the application was “broken.” We had to instill incredible discipline in all areas of the organization that produced these pages – content creation, design and development – to make sure our content fit on these little pages.

As AOL moved away from our proprietary screen technology to an open web experience, we enjoyed the luxury of designing longer (and wider) pages. Remaining sensitive to the issues of scrolling from our history, we developed and employed practices for designing around folds:

- We chose as target screen resolutions those used by the majority of our users.

- We identified where the fold would fall in different browsers, and noted the range of pixels that would be in the fold “zone.”

- We made sure that images and text appeared “broken” or cut off at the fold for the majority of our users (based on common screen resolutions and browsers).

- We kept the overall page height to no more than 3 screens.

But even given our new larger page sizes, we were still presented with long lists of items to be placed above the fold – lists impossible to accommodate. There were just too many things for the limited amount of vertical space.

For example, for advertising to be considered valuable and saleable, a certain percentage of it must appear above the 1024×768 fold. Branding must be above the fold. Navigation must be above the fold – or at least the beginning of the list of navigational choices. (If the list is well organized and displayed appropriately, scanning the list should help bring users down the page.) Big content (the primary content of the site) should begin above the fold. Some marketing folks believe that the actual number of data points and links above the fold is a strategic differentiator critical to business success. Considering the limited vertical real estate available and the desire for multiple ad units and functionality described above, an open design becomes impossible.

And why? Because people think users don’t scroll. Jakob Nielsen wrote about the growing acceptance and understanding of scrolling in 19972, yet 10 years later we are still hearing that users don’t scroll.

Research debunking this myth is starting to pop up, and a great example of this is the report available on ClickTale.com3. In it, the researchers used their proprietary tracking software to measure the activity of 120,000 pages. Their research gives data on the vertical height of the page and the point to which a user scrolls. In the study, they found that 76% of users scrolled and that a good portion of them scrolled all the way to the bottom, despite the height of the screen. Even the longest of web pages were scrolled to the bottom. One thing the study does not capture is how much time is spent at the bottom of the page, so the argument can be made that users might just scan it and not pay much attention to any content placed there.

This is where things get interesting.

I took a look at performance data for some AOL sites and found that items at the bottom of pages are being widely used. Perhaps the best example of this is the popular celebrity gossip website TMZ.com. The most clicked on item on the TMZ homepage is the link at the very bottom of the page that takes users to the next page. Note that the TMZ homepage is often over 15000 pixels long – which supports the ClickTale research that scrolling behavior is independent of screen height. Users are so engaged in the content of this site that they are following it down the page until they get to the “next page” link.

Maybe it’s not fair to use a celebrity gossip site as an example. After all, we’re not all designing around such tantalizing guilty-pleasure content as the downfall of beautiful people. So, let’s look at some drier content.

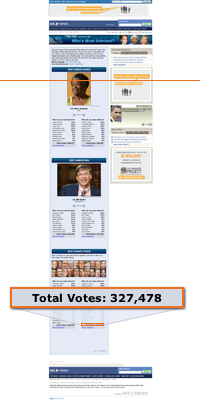

For example, take AOL News Daily Pulse. You’ll notice the poll at the bottom of the page – the vote counts are well over 300,000 each. This means that not only did folks scroll over 2000 pixels to the bottom of the page, they actually took the time to answer a poll while they were there. Hundreds of thousands of people taking a poll at the bottom of a page can easily be called a success.

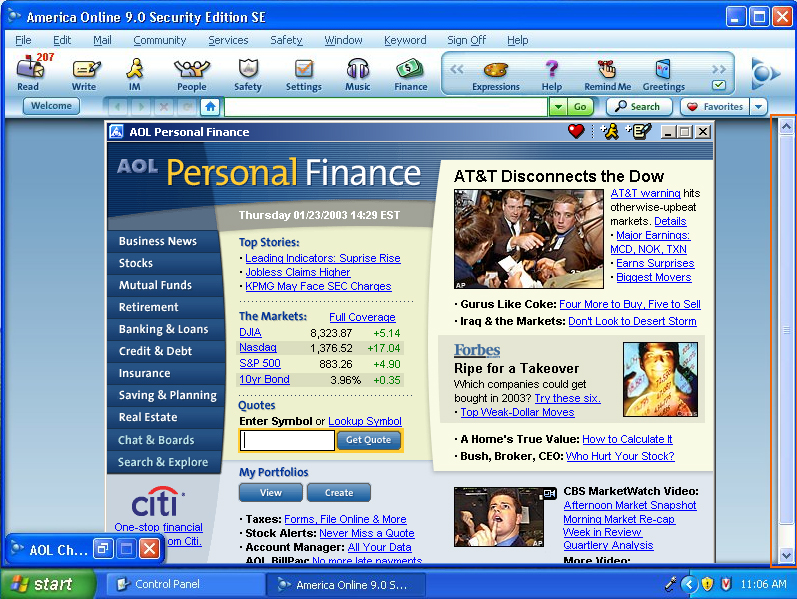

But, you may argue, these pages are both in blog format. Perhaps blogs encourage scrolling more than other types of pages. I’m not convinced, since blog format is of the “newest content on top” variety, but it may be true. However, looking at pages that are not in blog format, we see the same trend. On the AOL Money & Finance homepage, users find and use the modules for recent quotes and their personalized portfolios even when these modules are placed well beneath the 1024×768 fold.

Another example within AOL Money & Finance is a photo gallery entitled Top Tax Tips. Despite the fact that the gallery is almost 2500 pixels down the page, this gallery generates between 200,000 and 400,000 page views depending on promotion of the Taxes page.

It is clear that where a given item falls in relation to the fold is becoming less important. Users are scrolling to see what they want, and finding it. The key is the content – if it is compelling, users will follow where it leads.

When does the fold matter?

The most basic rule of thumb is that for every site the user should be able to understand what your site is about by the information presented to them above the fold. If they have to scroll to even discover what the site is, its success is unlikely.

Functionality that is essential to business strategy should remain (or at least begin) above the fold. For example, if your business success is dependent on users finding a particular thing (movie theaters, for example) then the widget to allow that action should certainly be above the fold.

Screen height and folds matter for applications, especially rapid-fire applications where users input variables and change the display of information. The input and output should be in very close proximity. Getting stock quotes is an example: a user may want to get four or five quotes in sequence, so it is imperative that the input field and the basic quote information display remain above the fold for each symbol entered. Imagine the frustration at having to scroll to find the input field for each quote you wanted.

Where IS the fold?

Here is perhaps the biggest problem of all. The design method of cutting-off images or text only works if you know where the fold is. There is a lot of information out there about how dispersed the location of fold line actually is. Again, a very clear picture of this problem is shown on ClickTale. In the same study of page scrolling, fold locations of viewed screens were captured, based on screen resolution and browser used.

It’s a sad, sad thing, but the single highest concentration of fold location (at around 600 pixels) for users accounted for less than 10% of the distribution. This pixel-height corresponds with a screen resolution of 1024×768. Browser applications take away varying amounts of vertical real estate for their interfaces (toolbars, address fields, etc). Each browser has a slightly different size, so not all visitors running a resolution of 1024×768 will have a fold that appears in the same spot.

In the ClickTale study, the three highest fold locations were 570, 590 and 600 pixels—apparently from different browsers running on 1024×768 screens. But the overall distribution of fold locations for the entire study was so varied that even these three sizes together only account for less than 26% of visits. What does all this mean? If you pick one pixel location on which to base the location of the fold when designing your screens, the best-case scenario is that you’ll get the fold line exactly right for only 10% of your visitors.

So what do we do now?

Stop worrying about the fold. Don’t throw your best practices out the window, but stop cramming stuff above a certain pixel point. You’re not helping anyone. Open up your designs and give your users some visual breathing room. If your content is compelling enough your users will read it to the end.

Advertisers currently want their ads above the fold, and it will be a while before that tide turns. But it’s very clear that the rest of the page can be just as valuable – perhaps more valuable – to contextual advertising. Personally, I’d want my ad to be right at the bottom of the TMZpage, forget the top.

The biggest lesson to be learned here is that if you use visual cues (such as cut-off images and text) and compelling content, users will scroll to see all of it. The next great frontier in web page design has to be bottom of the page. You’ve done your job and the user scrolled all the way to the bottom of the page because they were so engaged with your content. Now what? Is a footer really all we can offer them? If we know we’ve got them there, why not give them something to do next? Something contextual, a natural next step in your site, or something with which to interact (such as a poll) would be welcome and, most importantly, used.

References

fn1. Jared Spool UIE Brain Sparks, August 2, 2006:”Utilizing the Cut-off Look to Encourage Users To Scroll”:http://www.uie.com/brainsparks/2006/08/02/utilizing-the-cut-off-look-to-encourage-users-to-scroll/

fn2. Jakob Nielsen’s Alertbox, December 1, 1997: “Changes in Web Usability Since 1994”:http://www.useit.com/alertbox/9712a.html

fn3. ClickTale’s Research Blog, December 23, 2006: “Unfolding the Fold”:http://blog.clicktale.com/2006/12/23/unfolding-the-fold/

Really like the article. In user testing, we still see some issues with visual cues that indicate the end of the page (like a horizontal line or too much white space).

On your question, “where is the fold”, there’s a new niche analytics application called FoldSpy (foldspy.com) which is worth looking into. They measure the exact fold size rather than screen resolution so you can see what percentage of your visitors can see what and use that to determine where you should be placing important content.

Lar

Very useful and elaborate article. I referenced to it from my latest blogpost (see http://www.almarvanderkrogt.nl/blog/archives/2007/07/plain_view_embr.html).

Very interesting research, but it would seem to me that it applies more to sites where users have already bought into the product (AOL, news/news aggregator sites, a favorite blog, etc). If users are still evaluating the product (a news site they are looking at for the first time or a site for a company they are consider purchasing something from), they may not be convinced to scroll down if the content above the fold isn’t useful to them.

I don’t think the issue is so much that users don’t know how to scroll anymore than readers not knowing how to flip over a newspaper. The issue is using the content above the fold to *convince* them to buy into and *flip* that newspaper.

This article is both inspiring and reassuring. The hardest part of web design and user interface design has been convincing people (clients, product owners) that users will flow through content if the design is compelling; just like someone working their way through a newspaper or analyzing a great painting or sculpture. Design is meant to stimulate and guide the user to the desired end result. The fold has always been considered a brick wall to many designers and this insightful study of how the users are really investigating the web helps to tear down the wall. I do hope everyone prints this out and mysteriously places it on the desk of any client or product owner 🙂

Great article.

Chris – you’ve got it right. The content is the key. If it’s good, users will follow it – and I think they will follow it even if they haven’t been to the site before. The design of the page is important of course, and great design can support that great content. But if the content isn’t good, well, then I certainly hope users aren’t scrolling to see more of it… 😉

This kind of information is priceless. Concepts and theory are great, but this kind of solid data helps in the real world that we spend most of our time dealing with.

Check out Apple’s latest Web design – they have dropped a section/site map at the bottom of each page. This kind of information has typically been at the top of the page, usually buried in dropdown or flyout menus. I suspect that it is working well in this spot. (I would be surprised if the breadcrumb is very well understood down there, though. To me, that still belongs at the top of the page. Just instinct – would be nice to know.)

I wouldn’t say that the fold is necessarily a “myth”. It is a real barrier albeit one that has been paved over to more of a speed bump because users have become accustomed over the years to using one of the more simple inherent functions of a browser, the scroll bar. Also, we, as in the UI designers, have no one to blame but ourselves for reinforcing the fold. If we have been responsible designers we are probably doing wireframes to scale (or close to scale) and our Visio templates are set to letter or legal in landscape orientation so that we can (and out clients can) print out our deliverables on regular paper. Our designs then tend to conform to this. We need to break away from this constraint.

As you suggest, keeping functionality away from the fold and to use visual cues to suggest that there is something worthwhile to scroll to, is the key. Again, as responsible designers, we can and should influence all of the folks that depend upon our deliverables – the business owners, visual designers and developers – to remember that the fold is real but not to be afraid of it.

Now, how about the right hand fold? Meaning, scrolling from left to right. Now that is a reality. Is that the next barrier to true freedom?

This aspect fascinates me as I observe my husband (boomer) and other non-tech casual users’ behavior. Every one of them, including those I introduced to using the web personally, grasped the scroll down function easily, almost intuitively, and use it regularly regardless of whether they are already involved in the content. Yet each of them backs right out from a visual overload without thinking to seek lower. When asked, they’ll say it didn’t occur to them at the time. It appears to me that the ‘too much’ above the fold has far more of an impact than the ‘what’.

Hi, this is all very valuable, I have been trying to convince my clients that people DO SCROLL, but I never had the figures and numbers, thanks a load for the effort….

One more thing to add, I have realized through out my experience with web interfaces, that I scroll down more often becuase of the Mouse Wheel, it is becoming much more convenient to scroll as soon as the page starts loading even before the content is totally ready, just to see if the page is active and there are things to see down there, then I switch away to some other window, and later come back with all determination to dance the page up and down before I settle on a point… I swear, sometimes, if the page does not scroll down, I get disappointed! or worse, feel the browser hanged, or the connection lost! 🙂

PS. someone mentioned scrolling left-to-right, I believe if we can break the text into columns of adequate width, and invent a mouse wheel that goes right ways, it is possible!

Howdy from down under! One of my kiwi colleagues forwarded me your article this morning! Congrats on your international reputation : )

Great article. I am still conditioned from my AOL days to be compulsive about keeping things “above the fold”. But it is slowly fading away–leaving me much more space and freedom for designing!

Hope all is well at AOL.

I tend to have a issue with scrolling too much to find something on a page and tend to like sites that tastefully cram as much of the important content as high as possible on the page. Take this one for a quick example, after clicking on a link that says Rate, I then have to scroll all the way to the bottom of the page to find a comment box and it appears that I have the ability to Edit, Delete or Ban someone else’s comments…? Why does this have to be all the way at the bottom of the page? It would have been better in opinion to add the comment box at the same point on the page where I clicked Rate the article, so with that being said I think it’s always best practices to tastefully Cram in as much content as possible above the fold.

The Home page is what grabs a users attention and makes them read on further, just as a magazine, newspaper, etc. We here at http://www.fiswebdesign.com employ the best practices of tastefully cramming in as much content above the fold and will continue to do so.

WOW, this was awesome. That 10% number was good to know, and makes total sense. Does that factor in things like toolbars?

And yeah, for anyone who remembers HTML 1, scrolling was required! I mean, browsing using Archie and the gang required scrolling, Word docs on a 9″ Mac screen required scrolling (remember how screen refresh actually made a difference in a document?), and so on. Almost like saying people didn’t know to tab to a new field in Lotus or BIOS settings.

What’s funny is when someone has a 22″ monitor at max res and squishes their window down to less than 800×600.

Thanks for this info!

— a fellow AOL’er

Milissa! Hi! A coworker out here in San Diego just sent this article around the company here. Lo and behold, it’s you 🙂

Sadly, I don’t have anything to add beyond repeating the “great article” and “I deal with this all the time” and “thank you so much for culling together some actual data” callouts.

(and Quig – hey! Down under, huh?)

Pardon my friendly but useless response…

Hi ! Great article !

I wholeheartedly agree. And now that we have all understood that users scroll, can we also all agree that designing pages for screens at 1024×768 is bad ? I mean, I have an old (but faithful) laptop running at 1024×768 when I am in holidays, my home screen runs 1182×864, my office screen is 1600×1200 and my office laptop is something like 1440×900. With CSS everywhere, why is everybody designing columns with a fixed size ? Right now more than half my screen space is white ! STOP, please, STOP. Do create designs that scale well horizontally too !

Thanks for your attention !

It’s funny that I’ve found this article now…

I’ve just had to re-design the homepage of an online travel agency so that all the search functionality (navigation, destination input fields, calendar, return / one-way selection, total days, travellers and submit button(s)) fits above the fold for users with 800 x 600 monitor resolution, despite the fact that only 3.6% of the company’s customers have their monitors set to this resolution – the rest being higher.

interestingly, of all the major OTAs (online travel agencies), only kayak.com attempts to fit the search functionality above the fold for users with 800 x 600 resolution.

undertaking this exercise made me question whether users with lower resolutions would really be put off using a site if key functionality went below their fold and they had to scroll to complete a task (as long as it was obvious that the functionality continued below the fold), or if they would simply click away (as the CEO feared). in this instance, 800 x 600 users would only have kayak.com to go to if they really hadn’t mastered the scroll.

it also made me wonder what the impact of having a design compact enough to be viewed within such tight dimensions would be on the majority of users with higher resolutions. i wonder if there are any studies to show the user experience impact of small, fiddly or busy designs on users with large resolution monitors? if we’re talking from a design or branding point of view ‘small’, ‘busy’ and ‘cramped’ aren’t good adjectives.

i have always believed that people with lower resolution monitors must be used to scrolling by now – their experience of the web is by necessity a scrolly one.

Your article is a really nice combination of expert opinion and hard quantifiable data. Great, great stuff. Especially as web users get more savvy and video resolutions get more diverse, the fold becomes less and less relevant as a design obstacle. In the early days (which I also remember well), UI design was as very much a process of protecting the user from what they did not understand. The entire online paradigm was new to them, a little scary, and very easily frustrating. But that’s definitely not the case anymore (except in certain cases, or involving specific demographics), and we should have the courage as UI designers to intelligently dismiss some of these old restraints.

Nicely done – and made more powerful by the data you share – which is great that you are doing that as well. So much of what we do we quantify within our own walls but rarely do we share outward. Excellent!

I thought this was wonderfully insightful article, but sincerely hope Boxes and Arrows will consider changing the title. The fold is not a myth. It is very real, as you rightly point out (well below the fold) in the third-to-last subsection. And yes, readers scroll – which Amazon and eBay have known for ages. Nevertheless, the fold (on any page) remains critically important.

What we’ve discovered during user testing over the years is that anything that determines site behavior (changing language, text size, adjusting volume, etc.) should be above the fold. Any “you are here” information (page title, breadcrumbs, etc) should be above the fold, as well as any feature used to initiate the visitor’s journey (global navigation, search, sitemap) although these should probably also be repeated in the footer. And as you point out (also in the third-to-last subsection), business-critical links (contact info, key landing pages, etc.) are best placed above the fold.

On the other hand, surveys and polls tend to do much better at the bottom of a page, particularly if they deal directly with page content (in other words, people need to read the page before they can comment on it). And convenience features that refer directly to page content (print this page, tip a friend) generally do better at the bottom of the page, although visitors seem to like redundant links at both the top and bottom of the page even if they only use the ones at the bottom.

Your very last paragraph about the bottom of the page being “the next frontier” is perhaps the most valuable advice of all; when people are through reading, give them a logical place to continue their journey. Like a magician forcing a card on an unsuspecting audience member, good websites discreetly create linear flows through their site. Visitors choose to follow your contextual lead, even though they have the option to move about freely.

I hope you’ll write this article, too, someday. In the meantime, thanks for sharing your thoughts and experiences.

Some contextual statistics might help to bolster your case. For instance, 300,000 votes to a poll sounds impressive — unless the page is getting 60 millions page views. (Also, was the poll available only in this one location? Was there a link directly to the poll somewhere?)

Insightful article and I can’t tell you how great it is to see someone (and groups) finally providing at least SOME research into this.

I work for a print company that has had an internet presence for over a decade, yet can’t seem to let go of the idea that practically everything needs to appear above the fold. As a result, the sites look extremely poor and unintuitive. Their traffic over the last few years has been flat or declining. So, they’ve finally taken stock and have started to consider a new design.

The challenge has been to help them understand that the fold or scroll-line (depending on who you work for) doesn’t guarantee increased traffic. To me, increased traffic only arrives via a combination of viral marketing, SEO and engaging content. The point of the fold, and I agree to someone’s earlier comment, is to use that space wisely, placing your most important content towards the top and making sure that critically important UX functions are easily accessible in that space as well.

Nice work Milissa!

Good article. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard clients (external, internal or “the bosses”) repeat in strategy or review meetings “must be above the fold” as one of the dozen things they “know” as absolute gospel truth for all kinds of web projects and engagements.

This would be a great series… maybe not “blasting the myths” but at least challenging them.

Great article! As you state, quality content is the key. With my scroll wheel mouse I don’t even notice moving down the page when I’m compelled to do so. The only time I become frustrated with scrolling is when key functionality is at the bottom of a long page, and fortunately that is happening less and less.

I confess: I was one of those who harped, “Above the fold, above the fold!” But after becoming a beta user for http://www.clicktales.com (which records users activities and let’s you actually watch them using your site), I observed that every single user scrolled when interacting with my site.

Yes, it’s intuitive that more important items should be above the fold–or at least closer to the top–but the myth that has been busted from me is that of usability guru, Jakob Nielsen, who stated at some point that “50% of users don’t scroll.” That is a myth that, if it ever was, no longer holds true.

Great article. Thanks for affirming what I thought the case already was about “the fold of the screen.”

I’ve had to push my team members to keep things above the fold, because we are developing a social networking site where the on screen layout and interactive elements are not ‘familiar’. We’ve found in user tests that people were misunderstanding things because some of the key interaction elements were below the fold – which, as you say, is one of the times that its important to keep things above the fold.

We found that people were trying to asses the page by what was visible above the fold – and coming to some grief as a result.

Very important topic for us web designers! The one thing I would add is that if you design a long webpage, make damn sure you don’t have a strip of white space where all the content seems to end, and it also happens to be at a place where statistically the bottom of the browser window happens to be for a given monitor size. This can fool users into thinking there is nothing more below this point and they may not scroll further.

This is similar to the point made by folks about giving clues that content is worth scrolling to below the fold. Make sure you don’t inadvertantly design this apparent end to the page just to line things up in a nice way…

Nice article Milissa. I completely agree that people are scrolling more, although I’d say that we should pay close attention to the goal of the page in question when talking about the fold. In Jakob’s most recent book “Prioritizing Web Usability” he mentions that on homepages (those that mandate a scroll), only 23% of users do so. On internal pages, the scrolling % jumps to 42%.

Also, I know we’re talking about web sites as a whole here, but for any company that is serious about SEO, we also have to talk about landing pages. According to the recent MarketingSherpa Landing Page Handbook, fewer than 50% of their testers scrolled the page. The biggest culprit for killing the scroll for them was actually text size. They said that the smaller the text size, no matter where the fold was, users almost never scrolled.

Anyway … my two cents. Thanks Milissa. I, too, think you should write a post about utilizing the bottom of the page. You know what they say about lists (especially SERPs). People read the top and the bottom, but not the middle!

Alan,

The problem with writing rules and publishing them in books as Nielson is so prone to do, it that behavior and the market dynamics change. It is great bait for those looking for a simplistic solution, but things do change. We still have to think and grow.

Could you put the “three clicks” myth to bed next, or has somebody taken care of that one already?

Don’t forget the role of hardware. In our usablity tests the mouse in the testing room has a scroll ball. 100% of the people scroll very naturally down our pages. Is this because of the mouse or the design. I’m not sure. It would be interesting to know how many users have mouses with scroll balls. I think we should require it of all users:)

I want to join in with the praise, here. I work for a company designing for several news organizations, and it was hard for me to not forward this to all of our site managers. I don’t want to repeat all of the good points that have already been made (certain content belongs above the fold etc.) but there is definitely a problem, especially with news sites, of cramming all of the “good stuff” above the fold, making the lower section of the page a boring wasteland of text links. It’s like reading sales fliers with several hundred pixels of fine print at the bottom.

It’s hard for a lot of people to realize that scrolling isn’t comparable to the more physical act of reading a newspaper — it’s quite easy to scroll and people enjoy finding good stuff lower in the page — even the laziest of news/information hounds can be coaxed into reading more because of the simplicity.

I have passed your article on to several co-workers — let’s see what kind of great sites we can build if we can convince the traditionalists to take full advantage of their sites.

Thanks for the article, I found it insightful. Interestingly, I do believe (anecdotally speaking) that one of the reasons why we scroll more comfortably is because of the popularity of blogs. We’ve gotten used to scrolling down for more. Also, practically every Facebook, Google and My Space page forces you to scroll and that’s where more and more users are spending time. So in my view the “myth of the fold” deserved to be blasted!

Great article & thanks for sharing your research!

I’ve forwarded the article to a bunch of marketers and old school print/newspaper people who are stuck in the old school media world. I’m hoping that they’re finally look at web pages differently then a magazine or newspaper, which are restricted by their fixed width and height 😉

I agree with your premise, but this article does leave me somewhat frustrated.

In the blog style examples (TMZ and News Daily Pulse) and the non-blog example of Top Tax Tips, the items that you are measuring are part of the main flow of content. This is what is taking the user down the page and I would expect that, given strong content, these items would do reasonable well.

I’m disappointed that the one non-main content flow example that is used, AOL Money & Finance, is the one that doesn’t provide any form of quantitative measurement.

“Users find and use the modules for recent quotes and their personalized portfolios even when these modules are placed well beneath the 1024×768 fold.”

Does this mean 2 users or 99% of visitors?

Even where numbers are used, they are provided as raw numbers without context or any basis for comparison or evaluation.

The Top Tax Tips example states 200,000 to 400,000 page views. Is this good? Is this 5% of the visitors or 95%? What would these numbers be if the content were presented without the need for scrolling?

I’m not disagreeing with the principles, only the lack of sophistication in the analysis. When people start throwing around specific measurements as statistical evidence, that evidence needs to be sound and fully disclosed. Otherwise it’s just as bad or worse than using words like “lots” or “many” or “most”. They could be worse because people will look at the numbers and accept them as unquestionable truths without real or complete research.

Good article. I haven’t done any researches as it is not my expertise but I am convinced that scrolling has been so widely adopted by users that it has had an impact on the mouse. Microsoft has added a scrolling wheel and Apple has added a scrolling ball to the mouse in order to make scrolling easier. This modification made on the mouse surely did not come out of the blue.

Kenneth – I completely understand what you are saying. I used the examples chosen from AOL because I could use them without having to get into the corporate murkiness of what numbers I am not “allowed” to share. It’s a tricky space and I make it a rule to avoid the lawyers at all costs. 😉 That is the main reason I reference the ClickTale study so often in the article. They can freely share *all* their numbers and do a much better job at statistical analysis.

I use the AOL examples to demonstrate the trends we are seeing. Those trends are echoed by the analysis in the ClickTale study.Getting people to click on certain things is our bread and butter, and the fact that so many page views and traffic is coming from items below the fold has been a boon. We’ve embraced it fully into our design strategy at AOL, so much so that we’ve redesigned entire sites based on this new information. Check out the new AOL news site for example. (http://news.aol.com/)

Everyone – Thank you all for the overwhelming response to the article. I wanted to add a little firepower to your everyday battles. I know we’re going to hear more and more good news about this topic.

FINALLY I found an article that puts the whole fold thing into perspective. My two biggest pet peeves are clients who only talk about the fold and how many “clicks” are involved in an interaction design.

There has been in my experience, with a wide variety of clients, way too much time spent in meetings talking about what’s above the fold or how many clicks there are. I think you’re right that this is a detriment to our users because we end up spending less time actually talking about how to solve an interaction problem, which involves a whole host of factors least of which is what content should go above the fold.

Thanks for this great article.

A critical variable missing from this dialog is the “bounce rate”, or the number of people who leave the site on the same page as they enter it. This number can range as high as 50% for sites that get visitors from natural search or PPC.

The fold is a pivotal point in this scenario, as the content above the fold has to convince the user that the page has value for the current information need.

On the other hand, I fully endorse the conclusion that splitting articles into multiple pages has no basis in usability and is in fact a user negative, while alas, a revenue positive design choice.

Great article. I have found many times in my experience that business people always talk about the fold, but hardly understand what it is. This is a great reference.

In usability tests, I’ve seen users naturally scroll. I’ve also seen them not scroll due to a “cul de sac” in the design that made them think they were at the end of the page. In general, my gut tells me that people like to scroll up and down a page to get a sense of what’s on it, just like I think people like to scrape the mouse across the screen to see what happens. Of course, both of those behaviors can be foiled when pages are too heavy / are built in such a way that they don’t render quickly and you can’t scroll soon enough. I have a hunch that people’s willingness to explore the full content of a page (instead of just eyeballing what’s above the fold) might have more to do with how fast the page renders and how fast they can engage with it – instead of the mere notion that content might be hidden below the fold. Hmmm… research idea?

Thanks for this article, Milissa. I couldn’t agree more. Users don’t like to scroll left to right, so obviously steer clear of that, but most users I’ve come across are quite used to scrolling vertically. In fact, often times once you’ve found an article that’s useful, you’ll find related articles at the bottom of the page. I’m sure I’m not the only people to browse that list and make a selection.

I also agree with Thomas Bouton’s comment about fixed column designs. All those sites that are still 800×600 cause unnecessary scrolling, yet leave much of my screen unused.

Just this week, a client asked us to modify their home page to move a few links above the fold.

We first asked if they would tell us, using their tracking tools, if those below-the-fold links were getting fewer hits than their sibling links above the fold.

Turns out those below-the-fold links are doing as well as the above-the-fold links. The client is saved several thousand dollars, we get to focus on what really matters, and site visitors don’t have to deal with an overwhelmingly packed user interface.

The lesson: first test to see if you need to move things above the fold or not.

As you say, content is key. Readers will scroll if they find useful and relevant content in the portion of the page that is first revealed to them. That’s all. No magical formulas needed. This is basic human nature.

To extend the analogy with print media, though, the first-visible segment of the opening screen of any page should be where you place the strongest emphasis and put your best stuff (and establish or re-confirm corporate identity). Navigation and search elements (if used) should be present there and easily interpreted. It’s not that people WILL not scroll, but they MAY not if you haven’t prepared a suitably intuitive path for them.

Tracking data may be useful in aggregate, but we should be careful how we interpret it. On a site that doesn’t get much traffic, you may not have enough data to draw any reasonable conclusions. Some people move on simply because they’ve hit a page or a site that was irrelevant to their needs. That’s no fault of the design.

Finally, we’re not just designers. We’re also users or consumers of this communications medium. I think we’d all be better off if we’d set aside a lot of the “conventional wisdom” and honor our own direct experience of functional and dysfunctional design. As Milissa wisely suggests, some conventional thinking doesn’t translate that well to this medium.

I know that many people scroll down to read my pages, but people who actually click on ads rarely click unless those ads are near the top of the page. I have tried just about every ad placement you could ever think of within the last year, but ads near the top always get the most clicks. From the middle of the page to the bottom, most people just don’t seem to want to click that far down. It’s true that people of the late 1990s and beyond have been willing to scroll, but it will take more skill than I have to get them to click on ads once they get down there.

As a informationarchitect of an interactive agency I have to say that the research and the considerations you made makes sense for the type of site you based the study on. Users’ behavior may vary depending on the type of content they’re browsing. And how deep the user in the website or content, how well-versed or involved the user is with the topic or website.

If you visit a website several times or a blog I totally agree with your study, but, entertainment sites, campaign sites, ecommerce destinations or, fundamentally, online services sites won’t have the “privilege” of risking conversion on a scrolling action. Do you have any research on that?

Great and useful article!

I do, however, agree with the last commenter. As stated in your article, IA, content, and design are integral to grabbing a users’ attention and enticing them to scroll down for more. However, I believe that user familiarity with the brand/content also impacts user behavior. I would venture to guess that most of the users coming to the sites mentioned above were familiar with the AOL brand and the content being delivered. I’m curious to know if there is similar research where the users are not familiar with the type of content, the subject matter, or even the brand.

On a separate note, I’m also curious to find out how the iPhone and similar portable devices are impacting acceptance of the scroll.

Thanks again for your article!

Nice article! I do totally agree with the comments saying that the familiarity with the site [also] affects the behavior. When reading my favorite newspaper (www.faz.de) I always scroll down because I know that *there* is what I am interested in (Auto, Travel, Computer). On the other hand I totally ignore the complete left column because I know I am not going to find something interesting to me (Politics).

Milissa, thanks for sharing this story!

Great article and a nice summary of the challenges that we sometimes face when dealing with Marketing, etc. requirements, where “everything” is almost equally important and must be above the fold. In my experience (both usability testing and log analysis, e.g., Site overlay in Google Analytics), people do tend to utilize the areas above the “fold” more, but this also greatly depends on the *type of content* and *task* that they are trying to achieve. If a page has an appropriate hierarchy that accommodates the user’s task, then the users will be willing to read (and scroll).

Hi Everybody,

Milissa, thanks for referencing our research in your article.

We just released a follow up research story “ClickTale Scrolling Report V2.0 – Part 1: Visibility and Scroll Reach” (http://blog.clicktale.com/2007/10/05/clicktale-scrolling-research-report-v20-part-1-visibility-and-scroll-reach/) .

This brand new research about scrolling behavior sheds new light about the way users browse the web. For example, we found that visitors scroll relative to page height. This means that about the same percentage of page views will reach the middle of a web page regardless of the actual page height in pixels.

We invite you to take a look at our research and stay tuned for part 2 in this series for even more useful information about scrolling habits.

Enjoy Reading,

The ClickTale Team

Jakob Nielsen, at User Experience 2005 presented a simple rule, that is simply to be logical: Users will scroll if they feel that something relevant is there. So if you have a list of items (like a full listing of articles on a blog, or a list of products), that overflows the fold you (as a designer) usually have nothing to worry about. Worst cases are the boxed layouts, that are trying to have a decorative graphics around each block, especially when a vertical spacing between boxes is on the fold line.

Great work! I’d wager that some of our most common design documents and presentation techniques make a noticeable contribution to the Myth of the fold, by asking people to imagine some of the most basic aspects of the user experience such as scrolling, zooming, movement, etc.

When asking reviewers to translate from paper to interface, or from concept to finished product, simple visual cues like the boundary of a common wire-frame in a design spec, or the need to turn a paper page to see the full contents of an interface in detail during a review session, serve to reinforce the Myth by creating a perceived barrier and separation.

It’s an old story, but one that I’ve seen play out time and again. There are quite a few ways to improve our design artifacts by explicitly indicating continuity that we all use (or should). But beyond researching the differences between actual user behavior on screens vs. the behavior expected based on review and launching an education campaign to redress the gap (who would pay for that?), I suspect the Myth will persist as long as our design artifacts and methods have discontinuities ‘built in’.

the only issue I have with “de-mythifying” the scroll pronouncements, is not stating when it does matter. What will happen is that deigners that suck at optimizing layout will point to your article as proof that it just never matters.

If I own a business and I have primary call to action driving my profits and it is buried below the fold because some designer put a billboard sized photo in the header, I don’t care that 76% of people in some study happened to scroll. I care that a 100% of my site visitors see the call to action. That other 24% means I lost a lot of leads.

And that 76% does not account for the bounce rate people who did not see the call to action.

Or if an action in one part of the interface changes the state in another but I don’t see it, that is also a problem.

Whenever I see people bust fold myths, they tend to point to content pages. Not landing or home pages. And I have never seen anyone point to a study indicating a benefit to a metrics goal benefitting by being below the fold. Metrics are improved by improved clarity and visibility for obvious reasons.

Unfortunately these reasons are not so obvious to many designers who are frustrated by fold and other optimization issues and point to articles like this as coclusive proof that the fold does not matter anymore.

It is true that there are cases where fold hysteria is overblown and I think that is the general point of the article. But I do wish these articles would reiterate scenarios where the fold does matter. It would help in dealing with lazy designers.

Just to be pedantic: The term “below the fold” originates from broadsheet newspapers, and refers to material on the lower half of the front page, not to material inside the paper. On news-stands, broadsheet papers are folded, and only the top half of the page shows.

TRiG.

I’d just like to add (and I haven’t really read all the comments here) that there are two important things about the fold. I’ll define the fold line as whatever the user sees on entry without scrolling. The first communication a visitor has with the site, intranet, application, etc., is going to be what they see on entry without scrolling. This sets the first impression of the company, organization, whatever, and must be treated that way (so the real question is how important are first impressions? VERY). The second issue is that all navigation and truly important information should appear on entry (as alluded to in the article). An analysis should be made in design as to what information is really important to users and what is secondary. Usually this is not a huge or difficult task and of course will come out in usability testing to some degree.

Another comment is that the whole issue of the fold relates mainly to news-type sites or pages, where the entry view is of content that is very important and may act as a contents list. Not all sites really have a direct correlation.

In FF3 at 1024×768, viewable window-height = 640px

In IE 7 at 1024×768, the viewable window-height = 595px

Milissa,

Let me add my thanks to you for your excellent article and others for useful comments here.

I know I use the mouse scroll wheel all the time – and more often the laptop touchpad scroll areas on the right-side and bottom.

This will help me focus my coaching of clients as these issues arise. Even though usability is a great concern and focus for me, it’s a secondary level for my Agile/Scrum PM consulting.

Thanks also, because this is another KITA I need to reorganize my website.

Jay

I like the article, and most of it is still true today. Of course it is important that your message is smack in the face, and thus visible above the pagefold.

Wheather users want to scroll or not, depends from situation to situation. Visitors will not always scroll.

It depends on the type of page and the type of website.

An nice article illustrating when users ant to scroll and when ot can be found at http://webusability-blog.com/page-fold-fact-or-fiction/. It also gives some good examples of how to use the area above the page fold.

This article has become a classic. I was forwarded this today and immediately thought back to when I first read this article-

http://www.thereisnopagefold.com/

You cite ClickTale.com research for your article, but it doesn’t really seem like your conclusions jive with Clicktale’s research:

“Most readers never scroll down, and when they do the drop-off rate follows a distinct pattern (see graph below). In fact, page areas near the top of the page get about 17 times more exposure than the areas near the bottom of the page, according to a research report by ClickTale. This means that everything important or newsworthy, or any call to action, needs to be above the page fold.”

(item #3 at: http://blog.clicktale.com/2009/06/04/8-brilliant-tips-that-boost-conversions/)