Something that I feel is overlooked by a lot of product designers is the second-hand experience of their product. That is to say, above and beyond the target user, who is affected by the product—and most importantly—what is their experience?

If the UX team has satisfied all the needs and desires of the target user, minimized their pain-points, and maximized their ability to enjoy the most common process flows, that is truly awesome—but how does the experience they design affect that person’s social circle? Do product designers currently see that as a question worth spending additional time and resources to answer?

The classical method of product design is for design considerations to be dictated by our insights regarding the target user, as well as the goals (often monetary goals) of internal stakeholders. But as tech continually permeates our lives in an increasingly personal fashion, I believe the need for second-hand experience analysis will begin to shine through.

The power of shared experiences

The experience of the target user is not isolated from the experience of the indirect user. Whether it happens immediately or eventually, the two experiences affect and influence each other.

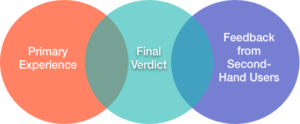

The target user, as entranced as they may be by their own experience, will continually receive feedback from others who were witness to this experience and will begin to judge the primary experience not only from their own frame of view but also from feedback received from constituents of their social ecosystem. The final verdict on an experience is often a group effort.

The need for second-hand UX

The need for greater focus on second-hand user experience is real. Many existing products already demonstrate a gap in the experience that affects indirect users.

One easy example of this might be the prevalence of texting and how it affects secondary users. What started as a flicker of excitement with the invention of smartphones (even if they were flip phones, sliders, or some other sort of archaic paperweight) has grown into something that has become a contentious social (and sometimes physical) habit.

Whether texting is positive or negative as a whole is a subjective judgement which requires a certain scope to even make a judgement feasible. For example, in a very surface-level, everyday efficiency scope, is texting positive? Probably so, at least for the direct user. But within a different scope, one that perhaps takes a look at the sociological/psychological effects of texting, would you come to the same judgement? Maybe, maybe not, but you’d certainly give it more thought.

Common responses to these deeper-level scopes consider issues such as how mobile phone usage creates a social distance between the primary user and secondary users. The dynamic, generally speaking, encourages less frequent and more shallow interaction between the person using the mobile device and the other people that may be around them. How often do you see people over-indulge in their electronic devices at the expense of paying attention to those around them?

Think back on personal situations where you might have been the secondary user. How did your feelings change towards the primary user? How about toward the product itself?

The smartphone—something that was intended to be a design solution for pain-points of communication efficiency, frequency, and accessibility—brings a complicated dynamic. It has raised questions with philosophical, psychological, and sociological underpinnings that should lead us to question the pros and cons of what I call short-term experience solutions, ones that satisfy the immediate user but don’t necessarily take into consideration the long-term effect these decisions have on the social ecosystem that encompasses the user.

That being said, I’m not here to rag on texting. On the contrary, I am totally addicted to texting and general mobile phone usage, despite the fact that its negative impacts are so apparent to me that I have recently started doing several exercises to try to correct my text neck.

Rather, I’d like to draw attention to the social dynamic that is created by tangible tech, be it a wearable, a mobile phone, a laptop, earbuds, or even a virtual reality headset. Each device, as well as the context it is used in, bears with it a social dynamic. These social dynamics are a much more important part of the experience of a product than the field of UX / product design would demonstrate historically.

I do think that designing for the primary user should be of utmost importance—but I also think product designers need to start valuing how the primary user’s interaction with the product affects their relationship with their social environment.

There is precedent to support an increased focus on second-hand user experience. We’ve read about the social implications of addictive smart-phone usage, the unintended negative interpretations of checking your Apple Watch, and of course the privacy concerns of wearables like Google Glass.

If you somehow think we’ve seen the peak of socially-permeating tech, think again. Technology is only going to continue to penetrate our lives as time passes, further warranting the need for considering second-hand UX.

The big question

This raises the question: When will second-hand UX become an integrated concern within the practice of UX?

Undoubtedly, product designers are concerned to some extent about how their products may affect second-hand users, but how often do we actually involve indirect users in the discovery and validation portions of our design process? To what extent are second-hand users a driving force behind how we generate requirements? (How many times will I say “second-hand”?)

Making this concept of valuing the experience of indirect users a top of mind concern could drastically alter the way UX practitioners do their work.

Just imagine the potential shift in focus for user research. Direct observations of people near someone using their virtual reality / augmented reality headset. Surveys, interviews, and focus groups inquiring about the experience that people had when their friends were using their new smart-watch. The possibilities are vast.

One way to utilize second-hand user research would be to engage existing UX assets, but with a new twist. Instead of traditional personas, we could have second-hand personas that examine the demographics, behaviors, likes and dislikes, proficiencies and deficiencies, and other attributes of the indirect user of a given product / experience. Who is our typical second-hand user? How might we describe them?

Similarly, UX practitioners could start developing second-hand journey maps that divulge the way an indirect user is thinking, feeling, and acting for each action that the primary user takes in their experience with the product. How did you feel as your friend watched a video on their virtual reality headset? What action did you take when your coworker started working next to you with their earbuds in? What were you thinking when your roommate used a voice command on Amazon Echo to lower the song you were listening to?

This shift in focus could open up a whole new realm of UX research and design that could lead to interesting new experiences.

Collaborative mode for VR headsets where multiple people share the same vision? More functionality built into health informatics for sharing data from person-to-person? Socially-contextual settings to limit notifications and keep users engaged in the real people that surround them? Maybe, maybe not. One thing is for certain: The ability to definitively and accurately decide how and when to implement design patterns like these will be dependent on empathizing with indirect users.

Next steps

So why is this important? Why should we care what indirect/second-hand users think or feel?

From a monetary perspective, the answer is simple: Purchase and usage considerations do not end at how the product/service will affect the buyer. Considerations extend into how it will affect the things they care about (which transitively affect them)—most often being their relationship with other people.

From a philosophical perspective, a lack of care about the psychological and sociological toll our products may take on users could drastically alter the concept of a traditional society altogether. It’s better to recognize and reverse potentially harmful design patterns now before habits and cultural beliefs lose sight of social concerns that were once fundamental. Despite popular belief, money and societal good do not have to be mutually exclusive. Let’s start taking second-hand experience into consideration and make it a core part of the way we practice UX.

I’ve been keeping these second-hand users in mind for a while, but mostly in terms of how they relate to the direct personas in Enterprise Software design. I tend to refer to them as “shadow personas” or “indirect personas”.

They don’t directly interact with the product I work on, but their lives will be affected by the work done by the people who do. The lives of the people who do work with my product will, therefore, be affected by them in return. If I’m providing a means by which Alice can do something and put the result on Bob’s desk (or in his inbox), the persona who’ll do the work is Alice, but the person who gets the direct payoff is Bob.

I can’t make Alice happy with my product unless Bob is happy… so I have to design as much for Bob as for Alice, even if Bob will never touch what I design.

I hadn’t considered this in the sense of “person sat next to somebody using an app on their phone” before, but now that you’ve mentioned it, it’s just as true there. Can a user truly be happy using your progressive web app on their phone if their loved ones are staring at them with daggers in their eyes the whole time they’re using it?

This article tells me it might be a good idea to dust off my old blog post on the topic (http://www.eggbox.org.uk/article/the-rise-of-the-shadow-persona/) and refresh it with some updated thinking. Thanks!

From a monetary perspective, the answer is simple: Purchase and usage considerations do not end at how the product/service will affect the buyer. Considerations extend into how it will affect the things they care about (which transitively affect them)—most often being their relationship with other people.