This is the third in a series that has become real-life examples of taxonomies found in my kitchen. Part 3 of “Taxonomy of Spices and Pantries” looks at where and how facets can be used as multiple categories for content.

- Building the business case for taxonomy

- Planning a taxonomy

- The many facets of taxonomy

- Card sorting a kitchen taxonomy

- Tree testing

- Taxonomy governance

- Best practices of enterprise taxonomies

Using my disorganized kitchen as an analogy, I outlined in part 1 the business reasons why a kitchen redesign needed to focus on taxonomy. I’ve moved often and content migration gets pretty ugly in the pantry. After a while, content creators are quick to stuff things into the nearest crammable crevice (until we move again and the IA is called upon to reorganize).

In part 2, I started planning and outlining the scope of this kitchen taxonomy project. Who are its users and core stakeholders? How do they move around the kitchen? What content in this domain would be covered in this taxonomy and where do we draw the line?

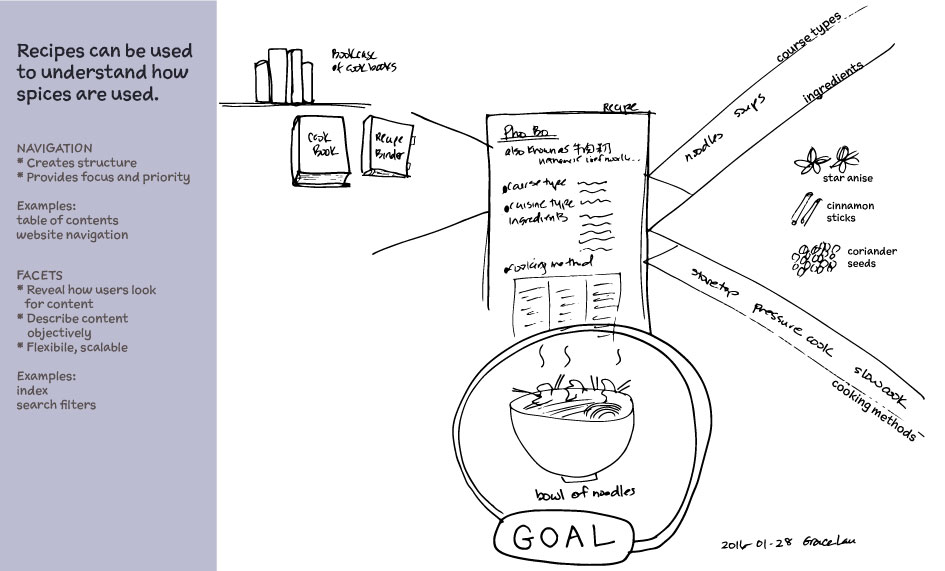

However, a simple list of pantry and spice categories is not enough to demonstrate the potential of taxonomies. A neatly organized spice drawer doesn’t represent a sound taxonomy unless there lies some underlying understanding of how the spices are used and in what context.

Moreover, taxonomies have many uses, and creating a retrieval scheme is just the beginning. For this, my kitchen pantry analogy expands to look at recipes as real-world use cases to understand the relationships of spices with one another and other facets as we explore how that content is used and referenced.

Bridging content across silos

With the holidays wrapped up, my son back in school, and packed school lunches back in the daily routine, I have to re-assess the existing kitchen taxonomies as I look through my recipes to figure out staples for lunch and dinner: Are we going paleo, or are rice and noodles back on the list? Am I cooking in the moment, or am I premeditating with slow-cooked meals?

I collect recipes in two main places: Evernote and a 3-ring binder. Recipes come from everywhere: recipes from cookbooks borrowed from the public library, recipes from cookbooks that I’ve purchased digitally or in print, recipes printed from notable food blogs and recipe databases, and even recipes from the plastic bag that holds the chocolate chips.

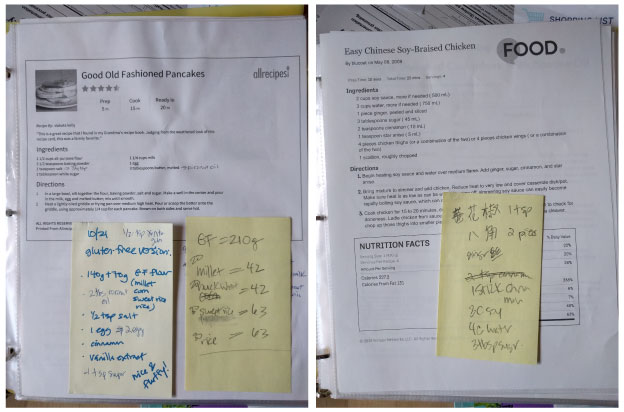

It usually starts off as someone else’s recipe printed from the web. I print out the ones I intend to try. Rather than simply saving them in Evernote (or in Pinterest for that matter), printing them out allows me to include it for sure during some meal and make adaptations. Trying to update Evernote in the middle of cooking makes for a rather grimy smartphone. Printed, the recipe is protected from kitchen splatters by sheet protectors. Sticky notes annotate what ingredients were substituted or should be tried instead next time, whether it had a favorable reception and merited an encore, or that the recipe had been attempted and should never appear again on the table (pig hock noodle soup, I remember you). This compilation of sticky notes documenting my trials turns the recipe into my own. Then I copy, add my notes in Evernote, and reprint the reworked recipe for the binder.

When you start thinking about your taxonomy, you should keep in mind that this is an opportunity to build a consensus across your content silos. See where content is being created and how it is being used. A kitchen example of a department silo is everyone buying their own container of baking soda and storing it on their personal shelf. Apparently, baking soda has at least six different acceptable names in Chinese. When my father-in-law couldn’t find “the one,” he went and bought another—when we already had a 5 lb. bag of baking soda from Costco.

Organizing in hierarchies

The thing about print is that there is only one way to organize content. Hierarchies dictate that content is categorized into fixed groups and mutually-exclusive sub-groups based on a single facet.

Imagine that I organize my recipes instead as breakfast, lunch, dinner, and dessert. Does that mean I can only have noodles for lunch and not dinner? With a hierarchy structured by meal time, I am limited.

Cookbooks perpetuate this way of thinking. Take a look at how Paleo Comfort Foods chefs Julie and Charles Mayfield organize their recipes in the table of contents:

- Starters and snacks

- Sauces and staples

- Soups and salads

- On the side

- Main dishes

- Desserts

Although one-dimensional, hierarchical taxonomies exist to create structure and provide focus.

As the binder grows to include more recipes, these groupings help provide organization and avoid a massive dump of recipes at the back of the binder:

- Soups

- Noodles

- Entrées

- Appetizers

- Sweets

At the same time, when compiling a meal plan for the week, …er, day, flipping through a section of entrées wouldn’t divert me to bake madeleines for a whole afternoon.

Organizing using facets

In print, facets are the the alphabetical index at the back of the binder. For a hardcopy cookbook, it’s definitive: Page numbers won’t change, recipes won’t be added until a second edition, and the ways you can understand the recipes are limited. The table of contents and the index of facets at the end of the book are set. Imagine the time and effort to maintain an index for a constantly changing recipe binder.

Organizing recipes by facets instead of a singular hierarchy is an opportunity to discover many dimensions of understanding recipes and the uses thereof. Identifying the various facets allows us to use more than one taxonomy at a time in the system.

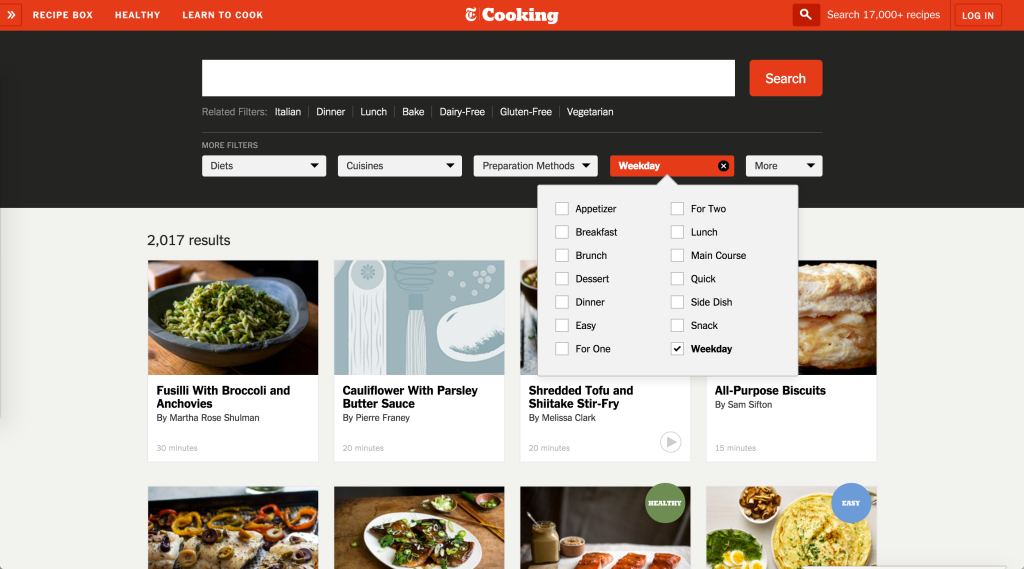

Thus, a faceted taxonomy for content saved digitally has a better chance of survival. It is scalable, flexible, and changeable at a moment’s notice. Facets used to classify content are not just used for navigation (in a table of contents) or a curated list of key terms (in an index). Facets can be used as search filters, as an interactive label, or as metadata embedded in the content.

Deciding on facets

But how will I determine which facets to use? By taking content and breaking it down into its smaller components, I would be able to describe the recipe enough to find it again.

Take a recipe for Phở Bò (Vietnamese beef noodle soup). Pho can be classified as a noodle dish and a soup. It has a cultural origin. It can be cooked stovetop for ten hours, slow-cooked for eight hours, or pressure-cooked for one hour. It has a core mix of spices to create that unique flavor.

A quick web search pulls up multiple variations of the basic pho recipe. One version from Jaden Hair’s Steamy Kitchen has a somewhat different mix of spices from another version listed in Michelle Tam and Henry Fong’s Nom Nom Paleo: Food for Humans.

With so many duplicate recipes of the same dish, how do I determine the one definitive, reliable pho recipe that I can adapt to my family’s taste? I’ll have to try them all.

Meanwhile, would pho turn out differently if I use a different cooking method? Does it make sense that I have separate pho recipes written for the slow cooker, pressure cooker, and stovetop? I’d have to have strict content governance rules in place to keep this binder well-maintained.

Moving on, is the hardware used an important characteristic to describe the recipe? Yes, definitely. The equipment being used has a direct impact on how much time is spent cooking. For instance, I would search for slow-cooker recipes so that I can come home to a hot dinner in a pot.

Choosing the correct term to use in my faceted taxonomy is another consideration. Do I use the brand name as the preferred term or the generic reference? For instance, the recipe could be classified using the brand name “Crock Pot” or the generic term “slow cooker.” Which term would I most likely use or search for?

Determining the facets used in a taxonomy is all about understanding the content and the user’s needs and workflow.

Do I have banh pho noodles? I’m not an expert in Vietnamese cuisine; I just like to eat pho. How could I learn more about these noodles and how to cook them? Those are the noodles that you specifically use for pho. If it’s the fresh ones, they should be stored in the fridge and used sooner than later. If they’re the dried ones, they should be in the pantry with the other dried noodle types, including somen, ramen, vermicelli, and Italian pasta. Expanding this taxonomy to include pictures and a description of general uses and nutritional benefits turns this taxonomy into a learning tool.

A Chinese household usually has oxtails and chicken feet around for making soups and broth. Sometimes I could end up with an overflow of oxtails sitting in my freezer due to nice deals at the supermarket. How can I find all the relevant recipes that use oxtails? Including ingredient as a facet also helps focus a general recipe search.

What about time spent in preparing and cooking? I often need to retrieve recipes that take 30 minutes or less. Depending on which cooking method is used, the time spent can vary from 2 to 10 hours. It’s 3 hours to expected dinner time, and I need a recipe. This is an important enough characteristic for recipes that you often see “Quick” or “Easy” as popular facets used across cookbooks and recipe repositories.

When you start developing your taxonomy, you’ll want to start by brainstorming facets based on your content. See which ones are more inclusive and which are too exclusive. “Brand” may seem like a good facet… but for a product taxonomy. Consider the need of capturing all your Lee Kum Kee sauces in one place. For the average household kitchen, “brand” may be unnecessary.

Once you have your preliminary set of facets, evaluate them against your users: Will all of your users use all of the facets, or are there natural subsets?

My in-laws often bring tea boxes back as gifts, and we supplement our tea selection with other tea types, including green, black, and herbal teas like chamomile and chrysanthemum. My mother-in-law knows which teas are more well-known and satisfying to bring out for gongfu tea when we have company. For my users, the origin of a tea is a natural start of the conversation.

Dinner’s ready!

In this part of the series, I’ve shown the beginnings of a taxonomy that could unify both the recipe content as well as the spices and pantry content. It would streamline and optimize the daily task of meal planning and preparation by enabling different ways to search and retrieve recipes.

A taxonomy isn’t simply a controlled list of spices and pantry items. A taxonomy may be extended to the organization of a recipe binder (navigation), the recipe format in Evernote (metadata), and the cookbook library. Making use of taxonomy in these various ways, I’m able to optimize the search and retrieval language being used and bridge those content silos.

In preparation for my next post on card-sorting, I have put together a card sorting exercise that shouldn’t take more than 15 minutes, unless you enjoy exploring ways to organize chaos like I do. I walk through the entire process of getting a card sort from planning to analysis and show how a card-sorting exercise can be used to gather user research and inform your taxonomy. Your responses will inform the analysis for the next post on using card sorting to gather user research.

The study is open until February 7, 2016, and I’m offering 1 lb. of assorted chocolates from See’s Candies to two lucky people.

Thoroughly enjoyed this analogy. Made it a breeze to wrap my head around facets, thank you! Looking forward to the next post.

If you haven’t already, you should check out “The Discipline of Organizing” by Robert Glushko. It’s not only great content relevant to your field of interest, it’s changing the way eBooks are made and used.

http://disciplineoforganizing.org

Scott