The rising popularity of the comic as an internal communication device for designers has increased our ability to engage our stakeholders as we build interfaces. Yet, social service agencies looking to provide services to hard-to-reach groups like immigrants, cultural minorities, and the poor have taken pride in innovative outreach methods. In situations where traditional printed matter is a barrier, graphical methods can be used very effectively to communicate with audiences.

From guerilla theatre to testimonials, posters to graphic instructions, users have benefited from alternative communication methods, particularly in situations where education or cultural barriers make it difficult for people to access services important to their well-being and safety. In some cases, the comic book format has been used as a way to help people get access to critical legal help. This case study from my time as a publication manager at the Legal Services Society (LSS) of British Columbia (BC) could inspire the use of comics outside the development process.

The situation

BC has over 253 First Nations tribes (known as “Native Americans” in the United States), which is about one-third of all First Nations in Canada. Seven of Canada’s eleven unique native language families are located exclusively in BC. When BC joined Confederation (Canada) in 1871, the provincial policy of the day did not recognize aboriginal title to the land, so no treaties were signed with the First Nations, unlike in other provinces.

Instead, the federal government made it a criminal offence for a First Nation to hire a lawyer to pursue land claims settlements and removed a generation of children to residential schools, where many were abused and traumatized. As a result, many tribes were left in an ongoing state of economical and social upheaval, with rampant unemployment, social problems, and poverty.

The Legal Services Society (LSS) in BC is the provincial agency that provides legal aid to poor and marginalized residents of the province. Prior to the crippling budget cuts the government imposed in the late 1990s, LSS also provided public legal education material to people who didn’t quite qualify for legal aid but certainly needed it. They may not have been quite poor enough, or they were poor enough, but legal aid didn’t cover their particular problem.

LSS knew that solving some of the smaller problems up front would keep them from escalating into larger problems—problems that would then qualify them for legal aid, but also would be devastating for their lives.

In 1995, the LSS asked its Publishing Program, where I was the manager, to collaborate with them on some self-help material for First Nations women. The Native Services Department wanted to help these women understand their rights in the area of family law, specifically around the issue of spousal violence. Based on the number of women who came to social service agencies for help, LSS recognized that there were a number of issues that were not well understood and, if caught early, could be addressed to prevent larger legal problems.

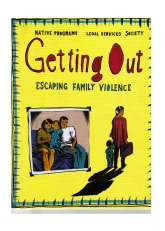

The agency decided that it was within its mandate to produce a publication for this population segment, and the two departments began the process of creating the publication that would eventually be called Getting Out: Escaping Family Violence.

Why the comics format?

LSS produced all publications collaboratively. In this case, the two departments explored different formats and ultimately chose the comic form. Comics’ graphical format could draw low-literacy women to pick up information off a publication rack. LSS had previously done one other publication in comic book format, which had worked for that audience.

The issue of family violence was a sensitive one, and the LSS had to be sure that the audience would not consider the graphical format of the publication condescending. To take the pulse of those who would use the publication, we conducted several focus groups in places where women would gather for learning (e.g. literacy, friendship, and women’s centers).

We used an approach that combined outreach, usability testing, literacy skills improvement, immigration intake, and legal education. We’d bring food and beverages, humbly ask questions, and be the learners instead of the teachers. Particularly with an all-women’s group, it was important to do something based around food. Participants would often bring their children, and they would ask us questions and giggle over our perspectives.

For this publication, a comic book format seemed to be a natural. The literacy levels in First Nations communities have been cited as being significantly lower than the general population, particularly in rural areas. Conveying the nuances of family law to a low-literacy population segment was one challenge; another was understanding specific cultural references that could be missed or become “localization” barriers.

Considerations similar to those for producing publications in different languages apply to those being translated from “majority culture English” to “minority culture English,” or same-language localization, so to speak. There may not be a language difference, strictly speaking, but significant dialectic differences apply, graphics are very culturally-specific, and emphasis differs between cultures. In this instance, we had to localize our content to make it relevant to our First Nations audience and not concern ourselves about whether the publication resonated with other people sitting in a legal aid waiting room.

Elements of development

The commitment of the LSS to create effective material for our users extended to all aspects of the publication process.

Authoring. The content creation was undertaken by seeking out a subject matter expert in the topic area, usually a lawyer or case worker in one of the field offices. The author gathered profiles, based on cases from offices around the province, and distilled the important legal information that went into the publication. For this publication, I hired a television screenwriter named Candis Callison, who was from the Tahltan band of First Nations, to provide an authentic voice for the comic book.

Editorial. The editorial process was done in-house. For this project, the process included editing the script to fit the comic book genre. I also worked with the artist to ensure that the number of panels would fit the booklet format, and the dialog would fit the panels. Once the substantial edit was done, in-house staff did the copy edit. Then the Native Services lawyer, also First Nations, reviewed the publication for legal accuracy.

Production. As positions opened in the department, I was able to hire more culturally and ethnically diverse employees so that, eventually, we were able to produce and proofread material for diverse cultures and languages. (We produced material for recent immigrants, as well, in Chinese, Farsi, Spanish, Punjabi, and Vietnamese.) The new staffed helped greatly during the back-translation, where a publication is translated back into English to ensure translation integrity. In this case, the back-translation was not for language, but to ensure that cultural references were effective.

Art, a critical element

An LSS employee was friends with a budding artist named Brian Jungen, who was of Dunne-za (a First Nations tribe) and Swiss background. His artwork provided authentic visuals for the initial book. His work now hangs in the Vancouver Art Gallery, amongst other places, and I like to think he looks back fondly on the project.

How the book came about

The structure of the book took shape as the artist and I divided the script into chunks to fit the drawings, and then the drawings as necessary. As the publishing program manager, I took on the role of substantive editor for the writing and graphics. I also worked with the artist to figure out how to get exactly enough panels to fit the amount of print space allotted.

The structure of the book needed to be in multiples of four pages—minus both covers, the copyright page, and the title pages—and couldn’t exceed 8 pages of actual panels, to control costs. The story had to stay coherent within these constraints and couldn’t focus on the local color at the expense of delivering the legal message. All of that took quite a bit of balancing to keep the interest, use the right level of language, and keep the key legal phrases that would be important for someone to know. In the end, it worked.

Much like any other localized material, we had the material checked by a lawyer to ensure that no legal concepts were compromised during the “translation,” and then the material was tested with audiences to determine effectiveness. The Native Services Department fieldworker took copies of the storyboards out on a road trip to band offices and friendship centers.

We held our breath until word came back through the “moccasin grapevine” that the results were well received. This feedback loop was critical because it provided the opportunity to incorporate any changes that came up from the test.

In the end…

The publication story line opens with a guy in a plaid shirt (it has to be a plaid shirt) having an altercation with his wife. Then they’re at a pow-wow in a truck (it has to be a pick-up truck) where she warmly greets an old (male) friend. Then they’re at a party where he’s being abusive to his wife. By the end of the publication, the wife has identified that his verbal and physical violence is not acceptable, gotten a restraining order by following a few simple steps, and taken some basic legal steps without incurring huge legal costs.

One of the dialog bubbles states “… If he tries to do any of these things, we will arrest him again for breach of bail,” and then explains what the term “breach of bail” means. Another panel explains that, “If you live in a rural community far from the cities, Crown counsel [a prosecuting attorney] travels from community to community. You may have a different lawyer at the trial.”

The “insider” cultural perspectives made me feel a bit of a voyeur, but that very characteristic was what made it so effective. The 8.5” x 11” saddle-stitched booklet was immediately identifiable on the publication rack by its distinctive graphics. Also, the title, Getting Out, reflected the vernacular used by women in the community caught in situations of domestic violence, so it was an instantly recognizable phrase.

The agency ran a modest print run of the publication, partly to contain printing costs in case of waste, and partly to gauge reaction to the publication. The booklets were distributed to legal aid offices, band offices, and other social service agencies where women were likely to go when they found themselves in marital distress. Offices and agencies were notified of its availability, and I mentioned it in passing during a radio interview.

The demand for the publication soon depleted the initial print run, and another was requested. The frontline workers liked the format, and handed it out to the women who didn’t quite qualify for legal aid but who clearly wouldn’t be able to afford a lawyer. Gathering post-production metrics was not a strong point at LSS, but by the measure of popular opinion, it was a winner, and the exercise was repeated with a companion publication entitled The Ministry Took My Kids, about parental rights when children are apprehended by social services.

I think my last comment got lost in the ether. If so, this one can be deleted.

Nice job on the article! As a comic artist and an interaction designer I’m always interested to see project like this. Comics are often seen as a second class medium, something that Scott McCloud argues against quite well in Understanding Comics. Did you encounter any resistance to using them along the lines of comics being “kids stuff”?

I’m also curious as to whether you and the artist went through a thumbnail/storyboard process to work out the pacing, panel placement, and story elements before beginning on the final artwork. It’s a process that serves the same purpose as paper-prototyping in UI design or playtesting in game design. Finally, are the complete comics available online in any form?

We – the artist, the writer, and I – did go through a thumbnail/storyboard process to work out the various aspects of the publication. I glossed over this part in the first paragraph under “How This Book Came About” but can describe it a bit more here. We had a field worker and in-house lawyer describe to the artist and script writer what a typical case and legal process would be. The artist went away and did some rough storyboards, providing some options for drawings. A few of them were just for comic relief (no pun intended) – we knew that they might reflect reality but we wouldn’t be able to use them. The writer wrote the dialogue, but because she was used to writing for television, sometimes she would write in actions which, of course, wouldn’t work in a static medium like paper. So I edited down the script in the first pass, and then worked with the artist to fit the script to his drawings. We calculated the right number of drawings, chose from the ones he’d drawn, added in a few more to be drawn, adjusted the script to fit, and so on, until it all worked.

Then, we had to run the final product by the legal team again to make sure that the fiddling we did hadn’t changed any of the legal context. I don’t think the publication is available online, but I could ask the agency if they could put it online or for permission to put it online. If they don’t want it online, it would be because laws have changed, and they wouldn’t want legal info to be out there that’s past its due date, so to speak.

One of the then project sponsors of these publications in the Native Services Department contacted me to clarify some points, which I’d like to state here: “As part of of Native Programs for LSS at the time I [Bernee Boulton] would like to point out that it was I, who along with Penny Desjarlais who came up with the initial idea for this project. I invited Candis Callison to the project. It was she who suggested the most talented Brian for the project.” By omission of the details, I did not intend to diminish the most important role of Bernee and Penny in sponsoring and directing these publications, and my memory failed me in remembering who had referred whom for the project. Without Penny, and certainly without Bernee, this project could not have happened, and certainly wouldn’t have been as successful as it was!

Rahel – thanks for the great case study. I liked the detail in how you managed the publication and appreciated how the article was down-to-earth, practical, and educational.

Why did the shirt have to be plaid, btw?