This past year we became acutely aware of how interconnected we all are. The toilet paper shortage gave the world a glimpse at supply chains, and the pandemic as a whole was a crash course in how our healthcare system can handle crises. It can be difficult to envision how we can make a difference even if we know the systems we live in don’t function well for everyone.

But what does this have to do with design?

Designers make choices that other people have to live with. It’s up to us, as designers, to make those choices count. Even though it may not feel like we have the agency to make these decisions in a way that benefits all, we do have the ability to think critically about the impact of the products and services we design for society. We won’t always have all the answers or always get it right. For systems thinking in design to work, there have to be strong partnerships to overcome complexity and make a difference.

Systems thinking is one way to think about how we can make more ethical and holistic choices as designers. It helps us “push beyond the immediate problems to see the underlying patterns, the ways we may leverage the system, and how we can learn and adapt as the system continues to change. It doesn’t make these challenges any less complex, but it gives us a way to embrace that complexity and work toward a healthier system” (Omidyar Group). Before we get into some practical ways to apply systems thinking to your practice, let’s define what systems thinking is.

To understand systems thinking, we must first understand what a system is. A system is the interaction or relationship of essential parts that are organized in a way that achieves something. A system must have parts that are somehow related to each other and there must be a purpose or function. The relationship of elements is integral to a system. And the outcome of all the interconnected parts is the function or purpose of the system. Furthermore, systems exist within systems. Where most of us rely on clocks throughout the day to wake up or get to a Zoom meeting on time, accurate time is essential for the internet or GPS to work.

Let’s take for example, an old-school wrist watch — the kind with an hour and minute hand. A wrist watch is typically made up of many small parts that work together to keep and display time anywhere you go. If we were to take a watch apart and lay the pieces all out on a table, we’d find springs, wheels, gears, gaskets, seals, rotors, etc. Once taken apart, the watch pieces are no longer a system because they are not working together for the purpose of telling time. Without the relationships, it is merely a collection of parts.

Replacing parts within a broken watch may not be as simple as it sounds. If the battery was dead, you wouldn’t grab a triple A. Even if you were able to connect the watch to a larger battery, it wouldn’t be as portable as it was before and now we’d be dealing with a slightly different system.

“Very often, this is the way we humans try to solve problems — by fixing the parts without accounting for how they work together and hoping that it improves the whole.”

Dr. Leyla Acaroglu

This is where systems thinking comes in.

Systems thinking is an approach which includes mindsets, processes, and tools that allow us to design more holistically.

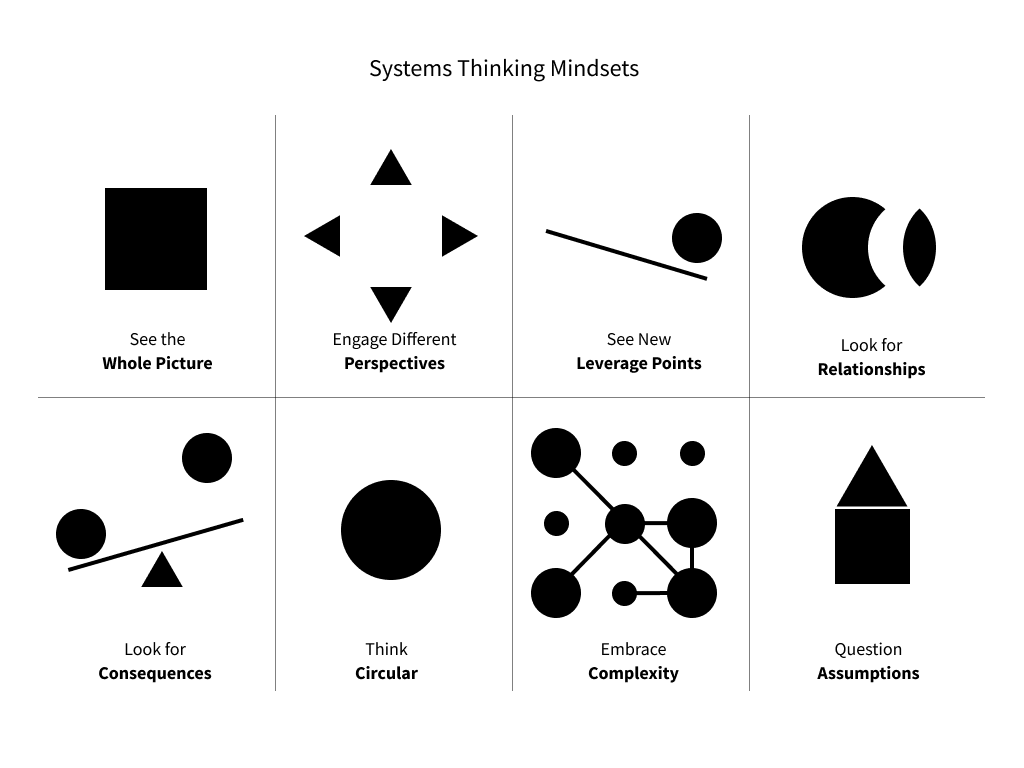

Mindsets

Have you found that you learn best by taking things apart or do you learn by building? For many centuries, scientists learned by taking things apart. In fact, this reductionist way of thinking is what led to the different specialties of science. It wasn’t until modern times that researchers began to pay more attention to patterns themselves and sometime around the 1920s, general systems theory was born (Kaufman).

Someone who engages in a systems thinking approach:

- Sees the whole picture

- Engages different perspectives to see new leverage points in complex systems

- Looks for relationships and how parts interact

- Looks for unintended consequences

- Thinks circularly; not linearly

- Embraces complexity

- Questions assumptions

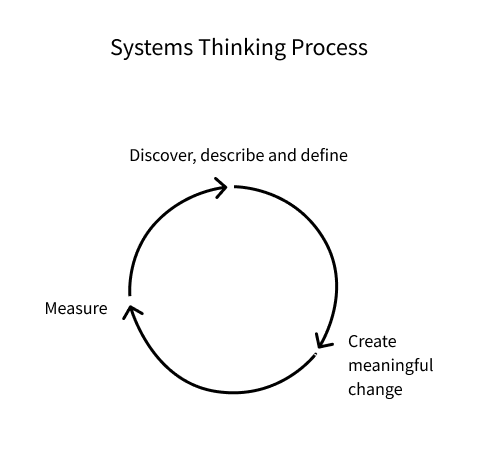

Process

There is no one way to do systems thinking. We like to use a process similar to Design Thinking.

- Discover, describe and define

In order to create effective solutions, we need to have a deep understanding of what is going on. - Create meaningful change

In systems thinking lingo, you might call this an intervention. - Measure

Continually learn from and adapt the system

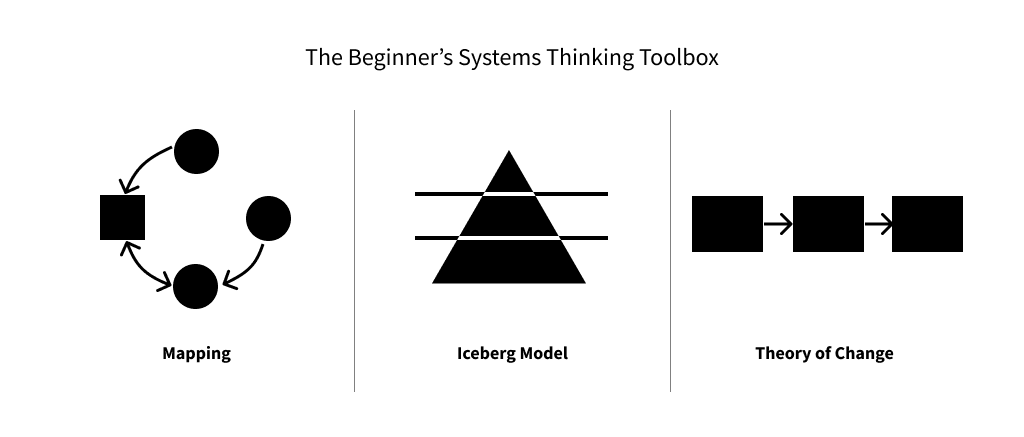

Tools

Look in a systems thinker’s toolbox and you’ll find many different tools. This is a great opportunity to integrate both systems and design thinking tools. For example:

- Mapping

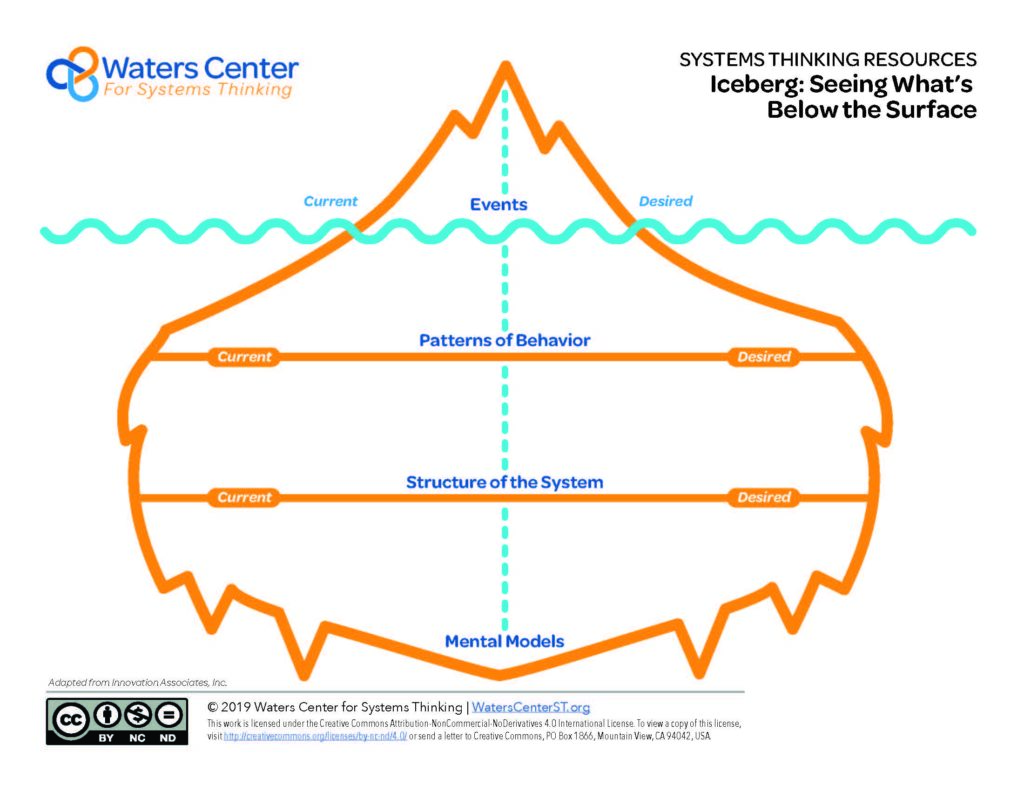

- Iceberg model

- Theory of change

“At its best, the practice of systems thinking helps us to stop operating from crisis to crisis, and to think in a less fragmented, more integrated way.”

Sweeny, Meadows

If you are a designer who is looking to make more positive, holistic change through your craft, keep reading for practical ways to begin practicing systems thinking.

How to Use Systems Thinking

One: Understand the Big Picture

Mapping

We like to use mapping to understand the complexity within which our problem or project lives.

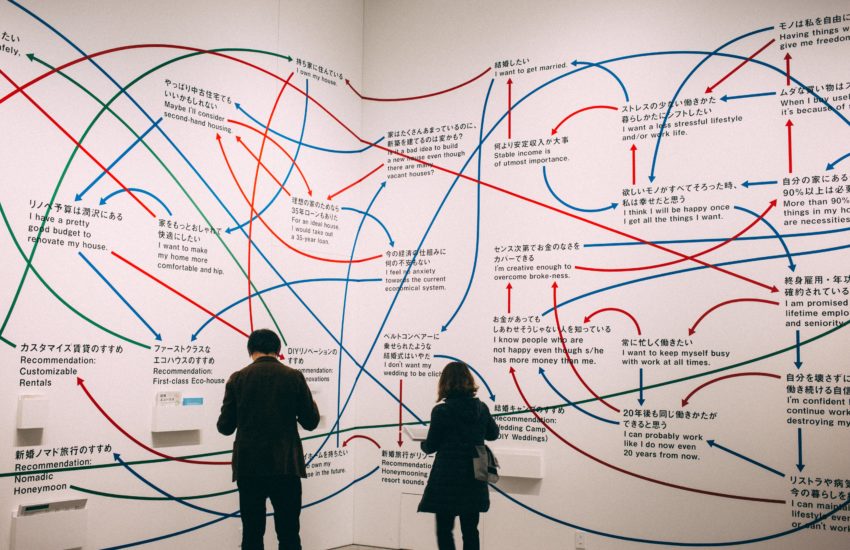

Mapping level-sets the playing field because it’s visual and offers all stakeholders involved the chance to understand it. Maps can be a living document used to understand the current state, to find solutions, and plan for the future. We recommend it as a collaborative effort. Create your maps with stakeholders. Share them early and often to ensure you have captured everything.

There are different ways to map — whichever flavor you use, it’s important to get down everything you and your stakeholders know. Maps can exist in any fidelity and importance should be placed on defining the relationships between elements because it’s the relationships that make a system.

Mapping types to try:

Once you understand the lay of the land, it becomes easier to know where you are going and how you are going to get there.

Two: Create Meaningful Change

Identify Points of Leverage

Even the most simple and straightforward solutions have downstream impacts. American systems scientist Peter Senge remarked many of the problems we face today are yesterday’s solutions. Solving a problem in a microcosm will feel like playing whack-a-mole, where we solve one only to have three more appear. Finding leverage points can help us with this risk by zooming in to find opportunities that make sense for the whole once we see the big picture and how it all fits together.

In order to identify these leverage points or areas for most opportunity or the best places to make impactful interventions, we need to analyze the patterns, structures, and beliefs that are all working to influence the problem area. In other words, we need to go below the surface. We’ll get more meaningful change if we go deeper into our systems maps and understand root causes.

Analysis

Mapping can be used to understand a clearly defined problem, and it can also be used to articulate or uncover problems. While mapping may help to clarify the problem(s), further analysis is needed to understand why it is happening.

Frameworks for analysis to get you started:

When making decisions about which problem areas to pursue, an understanding of behavioural insights can be useful. It is also helpful to agree on measures that will allow you to test your design hypotheses and provide evidence that the system improves. Once you identify the areas or leverage points where the system can benefit most, you can design interventions focused on them, hopefully avoiding negative consequences elsewhere.

Theory of Change

After zooming in and out in order to understand the system and identify leverage points, you are in a position to design the changes you wish to see. A number of tools can be used to assist in imagining what change might look like. A theory of change can be helpful in this process. Like an if/then exercise, a Theory of Change provides a framework for thinking about change interventions. There’s no set way to construct a theory of change, which can be either simple and small or very complex and large. The key is to start with outcomes, then work backwards to solutions.

This theory of change canvas outlines a thoughtful framework.

Three: Learn and Adapt

Systems thinking recognizes that all elements of a system are intertwined, creating constant flows. System structures contain feedback that inform the system’s behavior. “Everything we do as individuals, as an industry, or as a society is done in the context of an information-feedback system” (Forrester). Our daily interactions with systems involve a variety of feedback loops.

If you are driving a car, for example, you can tell how fast you’re going, if you’ve got enough fuel, and how much you’ve used the car by checking the dashboard. Feedback loops are vital to finding out where to make changes because they offer clues for what is happening within the system.

“At every stage of the design process we need to both zoom in on the user needs and zoom out to consider the systemic implications, oscillating continuously between these two equally critical perspectives.”

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (archives)

In A World of Systems, developed by the Donella Meadows Project, we learn how we engage in many systems everyday. One example in the video zooms in on a fish prepared for dinner from a local market which comes from a school of fish. Schools of fish are typically a self-balancing system, where the number of new fish (babies) help keep the population balanced as other fish die as a result of natural causes or predators. In the case of fisheries, there are often rules in place that help to balance the economic systems surrounding the stocks of fish, but with overfishing, the natural balance of the school of fish is thrown off. “The people who made those rules only had imperfect information on how many fish were left … and the system has been set up to deplete itself.” At the local market, the price of the fish surges as it becomes more difficult to source demand. This is one example of a feedback loop.

How might the price of the fish, types of fish available, or health of the fish change had the system been designed to respond to imbalances?

As you begin designing for change, consider how you might include ways to measure and respond to outcomes and include it as part of your solution.

Activating Change

The news is filled with stories about “broken systems” and it can often feel like the systems we interact with as designers are too broken and we have too little power to actually make positive change. But since it is the elements and relationships that make a system, there is no such thing as a broken system. The function of elements and relationships working together is the system. This is why we need to design with more intention and more attention to the out-of-bounds implications and impacts. We need to focus on the human element of a system and how it connects people, rather than solely designing for or fixing the ‘things’ we deem as broken.

Regardless of how big or small it may seem, everyone has the power to make a positive impact on the world with their “sphere of influence,” or the space they can reach at any given moment. As Donella Meadows has said, “a small shift in one thing can produce big changes.” We have an opportunity to drive positive change because we influence the outcomes of the products and services we design that influence the behavior of people who use them.

We can activate change by using systems thinking. In a world with really messy and complex systems, staying curious is the most hopeful thing we can do. In the middle of the frustration, it means encouraging each other to keep thinking intentionally about complex problems, courageously believing that with open minds we can actually make a difference and make these systems a little better for everyone.

Sources

- “Systems Practice Workbook.” Omidyar Group.

- Kauffman, Draper L. Systems One: An Introduction to Systems Thinking. Second ed., Future Systems, 1980.

- Sweeney, Linda Booth; Meadows, Dennis. The Systems Thinking Playbook: Exercises to Stretch and Build Learning and Systems Thinking Capabilities. Kindle Edition.

- Jay W. Forrester, Industrial Dynamics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1961), as cited in Meadows, Donella H., and Diana Wright. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015.

- A Visual Approach to Leverage Points, The Donella Meadows Project

Featured image by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash