Editors’ note: This “Book in Brief” feature here on Boxes and Arrows is from

Orchestrating Experiences: Collaborative Design for Complexity by Chris Risdon and Patrick Quattlebaum.

We’ll publish an excerpt, up to 500 words, of your book. The catch is that we’ll only publicize one book a month; first come, first serve. Other rules will certainly occur to us over time. Hit us up at idea at boxesandarrows.com.

Defining experience principles

If you embrace the recommended collaborative approaches in your sense-making activities, you and your colleagues should build good momentum toward creating better and valuable end-to-end experiences. In fact, the urge to jump into solution mode will be tempting. Take a deep breath: you have a little more work to do. To ensure that your new insights translate into the right actions, you must collectively define what is good and hold one another accountable for aligning with it.

If you embrace the recommended collaborative approaches in your sense-making activities, you and your colleagues should build good momentum toward creating better and valuable end-to-end experiences. In fact, the urge to jump into solution mode will be tempting. Take a deep breath: you have a little more work to do. To ensure that your new insights translate into the right actions, you must collectively define what is good and hold one another accountable for aligning with it.

Good, in this context, means the ideas and solutions that you commit to reflect your customers’ needs and context while achieving organizational objectives. It also means that each touchpoint harmonizes with others as part of an orchestrated system. Defining good, in this way, provides common constraints to reduce arbitrary decisions and nudge everyone in the same direction.

How do you align an organization to work collectively toward the same good? Start with some common guidelines called experience principles.

A common DNA

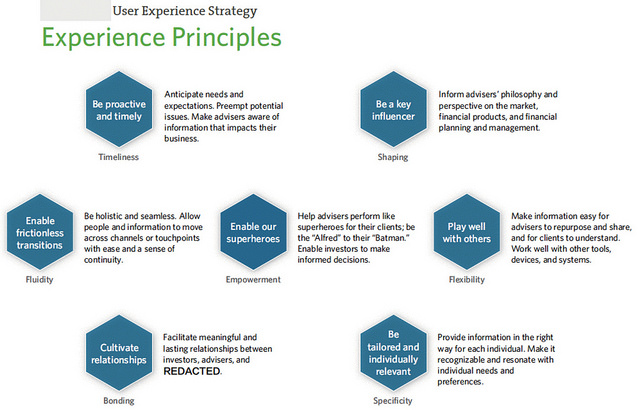

Experience principles are a set of guidelines that an organization commits to and follows from strategy through delivery to produce mutually beneficial and differentiated customer experiences. Experience principles represent the alignment of brand aspirations and customer needs, and they are derived from understanding your customers. In action, they help teams own their part (e.g., a product, touchpoint, or channel) while supporting consistency and continuity in the end-to-end experience. Figure 6.1 presents an example of a set of experience principles.

Experience principles are not detailed standards that everyone must obey to the letter. Standards tend to produce a rigid system, which curbs innovation and creativity. In contrast, experience principles inform the many decisions required to define what experiences your product or service should create and how to design for individual, yet connected, moments. They communicate in a few memorable phrases the organizational wisdom for how to meet customers’ needs consistently and effectively. For example, look at the following:

- Paint me a picture.

- Have my back.

- Set my expectations.

- Be one step ahead of me.

- Respect my time.

Experience principles are grounded in customer needs, and they keep collaborators focused on the why, what, and how of engaging people through products and services. They keep critical insights and intentions top of mind, such as the following:

- Mental Models: How part of an experience can help people have a better understanding, or how it should conform to their mental model.

- Emotions: How part of an experience should support the customer emotionally, or directly address their motivations.

- Behaviors: How part of an experience should enable someone to do something they set out to do better.

- Target: The characteristics to which an experience should adhere.

- Impact: The outcomes and qualities an experience should engender in the user or customer.

Playing together

Earlier, we compared channels and touchpoints to instruments and notes played by an orchestra, but in the case of experience principles, it’s more like jazz. While each member of a jazz ensemble is given plenty of room to improvise, all players understand the common context in which they are performing and carefully listen and respond to one another (see Figure 6.2). They know the standards of the genre backward and forward, and this knowledge allows them to be creative individually while collectively playing the same tune.

Photo by Roland Godefroy. License.

Experience principles provide structure and guidelines that connect collaborators while giving them room to be innovative. As with a time signature, they ensure alignment. Similar to a melody, they provide a foundation that encourages supportive harmony. Like musical style, experience principles provide boundaries for what fits and what doesn’t.

Experience principles challenge a common issue in organizations: isolated soloists playing their own tune to the detriment of the whole ensemble. While still leaving plenty of room for individual improvisation, they ask a bunch of solo acts to be part of the band. This structure provides a foundation for continuity in the resulting customer journey, but doesn’t overengineer consistency and predictability, which might prevent delight and differentiation. Stressing this balance of designing the whole while distributing effort and ownership is a critical stance to take to engender cross-functional buy-in.

To get broad acceptance of your experience principles, you must help your colleagues and your leadership see their value. You will need to craft value propositions for your different stakeholders, educate the stakeholders on how to use experience principles, and pilot the experience principles to show how they are used in action. This typically requires crafting specific value propositions and education materials for different stakeholders to gain broad support and adoption. Piloting your experience principals on a project can also help others understand their tactical use. When approaching each stakeholder, consider these common values:

Defining good: While different channels and media have their specific best practices, experience principles provide a common set of criteria that can be applied across an entire end-to-end experience.

- Decision-making filter: Throughout the process of determining what to do strategically and how to do it tactically, experience principles ensure that customers’ needs and desires are represented in the decision-making process.

- Boundary constraints: Because these constraints represent the alignment of brand aspiration and customer desire, experience principles can filter out ideas or solutions that don’t reinforce this alignment.

- Efficiency: Used consistently, experience principles reduce ambiguity and the resultant churn when determining what concepts should move forward and how to design them well.

- Creativity inspiration: Experience principles are very effective in sparking new ideas with greater confidence that will map back to customer needs. (See Chapter 8, “Generating and Evaluating Ideas.”)

- Quality control: Through the execution lifecycle, experience principles can be used to critique touchpoint designs (i.e., the parts) to ensure that they align to the greater experience (i.e., the whole).

Pitching and educating aside, your best bet for creating good experience principles that get adopted is to avoid creating them in a black box. You don’t want to spring your experience principles on your colleagues as if they were commandments from above to follow blindly. Instead, work together to craft a set of principles that everyone can follow energetically.

Identifying draft principles

Your research into the lives and journeys of customers will produce a large number of insights. These insights are reflective. They capture people’s current experiences—such as, their met and unmet needs, how they frame the world, and their desired outcomes. To craft useful and appropriate experience principles, you must turn these insights inside out to project what future experiences should be.

From the bottom up

The leap from insights to experience principles will take several iterations. While you may be able to rattle off a few candidates based on your research, it’s well worth the time to follow a more rigorous approach in which you work from the bottom (individual insights) to the top (a handful of well-crafted principles). Here’s how to get started:

- Reassemble your facilitators and experience mappers, as they are closest to what you learned in your research.

- Go back to the key insights that emerged from your discovery and research. These likely have been packaged in maps, models, research reports, or other artifacts. You can also go back to your raw data if needed.

- Write each key insight on a sticky note. These will be used to spark a first pass at potential principles.

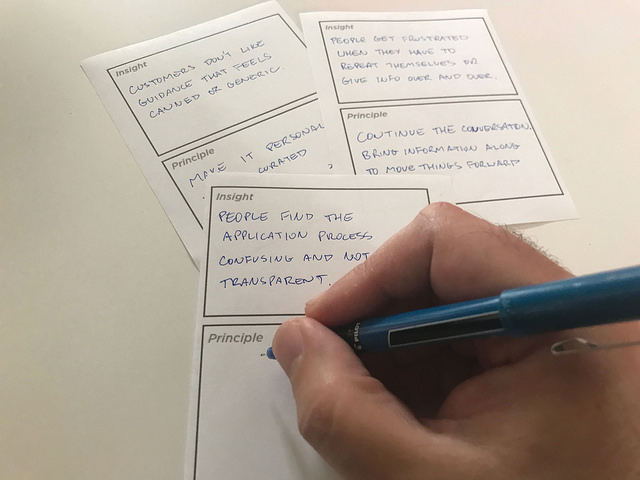

- For each insight, have everyone take a pass individually at articulating a principle derived from just that insight. You can use sticky notes again or a quarter sheet of 8.5″’’x 11″’ (A6) template to give people a little more structure (see Figure 6.3).

- At this stage, you should coach participants to avoid finding the perfect words or a pithy way to communicate a potential principle. Instead, focus on getting the core lesson learned from the insight and what advice you would give others to guide product or service decisions in the future. Table 6.1 shows a couple of examples of what a good first pass looks like.

- At this stage, don’t be a wordsmith. Work quickly to reframe your insights from something you know (“Most people don’t want to…”) to what should be done to stay true to this insight (“Make it easy for people…”).

- Work your way through all the insights until everyone has a principle for each one.

Table 6.1 From insights to draft principles

| Insight | Principle |

| Most people don’t want to do their homework first. They want to get started and learn what they need to know when they need to know it. | Make it easy for people to dive in and collect knowledge when it’s most relevant. |

| Everyone believes their situation (financial, home, health) is unique and reflects their specific circumstances, even if it’s not true. | Approach people as they see themselves: unique people in unique situations. |

Finding patterns

You now have a superset of individual principles from which a handful of experience principles will emerge. Your next step is to find the patterns within them. You can use affinity mapping to identify principles that speak to a similar theme or intent. As with any clustering activity, this may take a few iterations until you feel that you have mutually exclusive categories. You can do this in just a few steps:

- Select someone to be a workshop participant to present the principles one by one, explaining the intent behind each one.

- Cycle through the rest of the group, combining like principles and noting where principles conflict with one another. As you cluster, the dialogue the group has is as important as where the principles end up.

- Once things settle down, you and your colleagues can take a first pass at articulating a principle for each cluster. A simple half sheet (8.5” x 4.25” or A5) template can give some structure to this step. Again, don’t get too precious with every word yet. (see Figure 6.4). Get the essence down so that you and others can understand and further refine it with the other principles.

- You should end up with several mutually exclusive categories with a draft principle for each.

Designing principles as a system

No experience principle is an island. Each should be understandable and useful on its own, but together your principles should form a system. Your principles should be complementary and reinforcing. They should be able to be applied across channels and throughout your product or service development process.

Well-thought out and beautifully written. I’ll buy one!