Tree testing is an effective technique for evaluating navigation and taxonomy. In an environment devoid of visual design and cues, tree tests are useful for assessing existing site navigation and proposed site structure changes. Using my kitchen, I devised a plan to test the findability of my kitchen’s spices and pantries.

Card sorts versus tree tests

Card sorts are about organizing; they ask where would you put it? For example, in a card sort, a task would be to put things away after a trip to the grocery story or you cleaning up after I cook. Where would you store this bag of baking soda? (Aside: Misplaced baking soda is turning out to be a common theme across my posts.)

Tasks in a tree test are instead focused on findability and labels:

- Help me find <insert kitchen item here>.

- Where should I look based on these clues?

Also known as navigation testing, tree testing strips visual aids from a web site, condensing it to a collapsible, expandable folder tree. We don’t know the contents of the folder. The tree test asks where would you look for it?

Why tree testing?

In a card sort, you’re testing for the commonality of the cards. In a tree test, you’re testing the labels, not the cards.

In an open card sort, you’re asking for the user to help you generate labels for groups that they’re creating. In a closed card sort, the labels are predetermined and all the user is doing is group the cards under those labels.

Tree testing helps assess whether those labels make sense. In fact, I tend to use this as a way to benchmark an existing navigation or to test a proposed sitemap. In retrospect, if I’d thought about this six years ago, I should have conducted a tree test every time I moved to see if the kitchen was better organized over time.

Tree testing also helps validate nomenclature with your users and confirm whether you and your users have the same mental model.

Putting the tree test together

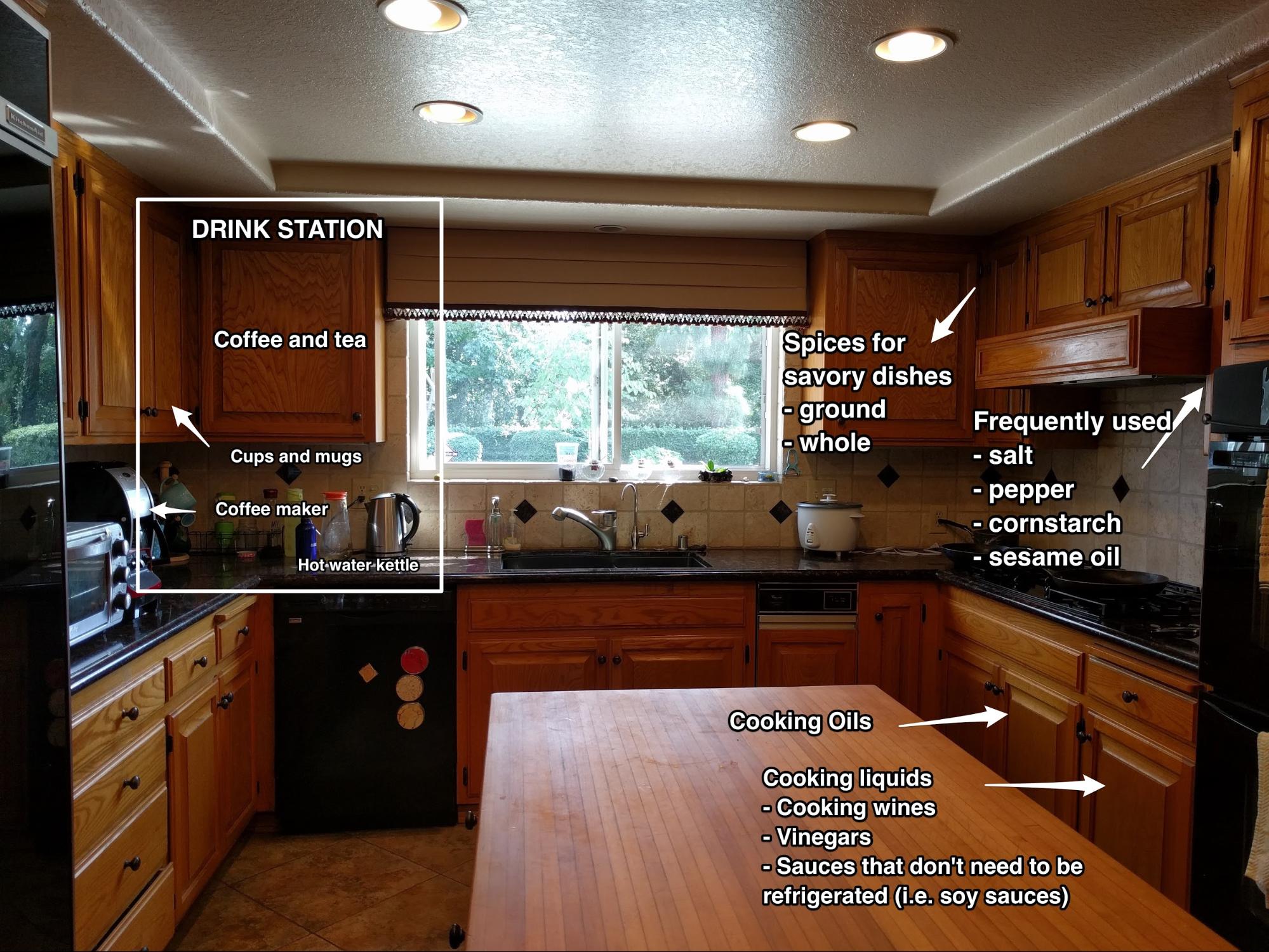

So far, I’ve conducted a content inventory and a card sort. My next mission was to take the labels generated from the card sort and apply it to areas in my kitchen. How did I want to label the areas in my kitchen to best reflect function and workflow?

The tree or sitemap

Tree testing focuses on using sitemaps (referred to as “trees” in Treejack, a popular software for this mission) to test navigation quickly. Once you have a sitemap and an idea of your users’ key tasks, you can start planning, executing a test, and iterating with revisions. There’s no dependency on the visual designer to make changes in Photoshop or on the interaction designer to create the prototype adjustments. This is all just making sitemap changes in a spreadsheet or a mind map.

This taxonomy had to consider the physical layout of my kitchen. At the same time, card sort findings indicated that some things should be stored in the refrigerator and frequent use items should be kept at the ready. If this were digital content, for instance, where I’m crafting a taxonomy for describing recipe content, physical space is less of a factor, never mind storage requirements.

Based in these deliberations, I used a mix of general location and descriptive purpose labels as the primary level labels in my sitemap. “Next to the stove,” “in the refrigerator,” and “in the pantry” are the three locations in the first tree.

For this kitchen taxonomy, I ran two rounds of tests. As the results of round one came in, I couldn’t stop myself from restructuring my kitchen along the way and subsequently creating a round two to test the new structure. It happens. Iteration is good. When you’re putting together your UX research plan, be sure to plan and budget for iterations.

In the first round, I focused on those three locations:

- Next to the stove

- In the refrigerator

- In the pantry

In the second round, I broadened the locations:

- On the countertop, next to the stove

- In the cabinet, next to the stove

- In the cabinets, below the stove

- In the refrigerator

- In the pantry

- Near the coffeemaker

The tasks

In both rounds of tree testing, the tasks I gave respondents had similar themes. The tasks were commonly-occurring scenarios in my kitchen whenever we have guests or are preparing for a yummy get-together.

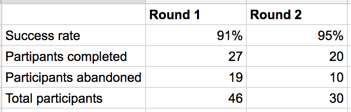

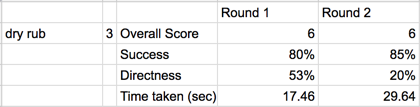

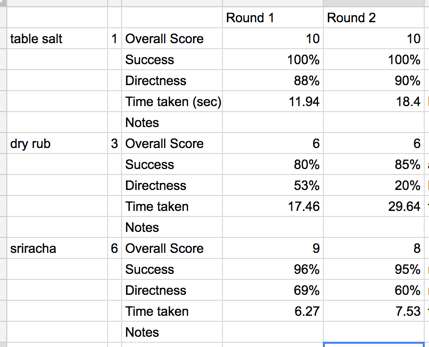

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

| Common-use/Training | My sister is visiting from out-of-state and is making fried eggs for breakfast. Where should she look to find salt? | My sister is visiting from out-of-state and is making fried eggs for breakfast. Where should she look to find salt? |

| Wildcard | It’s breakfast smoothie time! I want chia seeds added in mine. Where would you look to find them? | It’s late and I’m craving noodles after watching Korean dramas. Where can I find ramen noodles? |

| Spice item | For dinner this Saturday, we’re making BBQ ribs. Help me find the dry rub. | For dinner this Saturday, we’re making BBQ ribs. Help me find the dry rub to season the ribs. |

| Pantry/Baking | I’m trying to perfect a recipe for a childhood favorite snack, Hong Kong-style egg waffles. For this, I’ll need custard powder. Where would you look to find this? | We’re in a Thai mood for dinner tonight so I’m making coconut rice. Where would you look to find coconut milk? Either canned or boxed is fine. |

| Coffee and tea | It’s time for a coffee break! Or, if you prefer, time for that afternoon caffeine boost. I’m ready for some fresh brewed coffee. Where would you look to find the coffee beans? I’ll get the water ready. | It’s time for that afternoon caffeine boost. Could you get the Chinese tea out? Any one is fine. I’ll get the water ready. |

| Ingredient with questionable storage | We’re eating chicken stir-fry for dinner tonight. Do you need hot sauce? Where would you look to find Sriracha sauce? | We’re eating chicken stir-fry for dinner tonight. Do you like to eat spicy? Where would you look to find Sriracha sauce? |

The follow-up questions

After each task, I asked some follow-up questions to assess the ease of the task:

- Overall, how difficult or easy did you find this task?

- Any thoughts on how this experience could be improved?

I use a 7-point rating scale with 1 being very difficult to 7 being very easy. An open-ended question helps capture feedback right away while the task is still fresh in the user’s mind.

The recruit

Hopefully, you have a pool of participants you can send your test out to. You may want to check out Demetrius Madrigal’s Research Logistics, where he outlines how you might want to recruit participants similar to your target audience. Or you may send it around the office to whomever has 5-10 minutes to spare from watching cat videos. For my test, I had embedded it with my card sorting article and posted it across LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

The wait, the cringe, and the iteration

Once a tree test is running, the fun starts. The results start rolling in and you can start making adjustments for a second round if you want, which I did. You start seeing patterns after three people have gone through your test. Once the test reached the magic number of five participants, I made the first level of the tree broader. I expanded the top level branches to include the cabinet area next to the stove, under the stove, and the counter space next to the stove. I also designated an area for tea and coffee based the location of the coffeemaker/electric water kettle.

The satisfaction that comes with people-watching is doubly-true for monitoring test results. How are people reacting to this navigation? What made sense to them? What didn’t? And then, how many more people should I test this with to know if this is a universal concern?

How many people should I test with?

Clients often ask how many people should take the tree test. It depends on how comfortable you are with a higher margin of error. For more on statistics, you should check out Jeff Sauro’s Using Tree-Testing to Test Information Architecture.

At this point, you could potentially go into basic statistics and talk about confidence rates, sample sizes, and margins of error. How many participants would you have tested to be 95% confident that your users can find your content?

Say, there are about 100 people who would traverse through my kitchen in its lifetime (population size). Round 1 had 27 complete responses (sample size) and a success rate of 91%. Using the margin of error calculator with a confidence level of 95% (meaning there’s a 95% likelihood that the sample accurately reflects the attitudes of your potential taxonomy users), I determined that the margin of error is 17%. That means that there’s a 95% likelihood that between 74% (91-17) and 108% (91+17) of all the people in my kitchen would actually be able to find stuff in my kitchen.

Round 2 had a sample size of 20 people, of which 95% were able to find stuff in my kitchen successfully. Using the same formula, the margin of error is determined to be 20%. Note that the margin of error here has changed because the sample size is smaller. I can be certain that between 75% (95-20) and 115% (95+20) of people would be able to find stuff in my kitchen. Apparently, it’s a Very Organized Kitchen.

However, the difference between the two wasn’t very substantial. Ideally, I’d test with more people so that the margin of error is smaller.

Factors to consider when determining the size of the margin of error:

- Sample size: Use the number of participants who completed the test.

- Percentage: Use the worst case scenario (50%) if you want to determine a general level of accuracy. In my example, I used the overall success rate for each round.

- Population size: Use the number of people that the group your sample represents.

What KPIs should I look at?

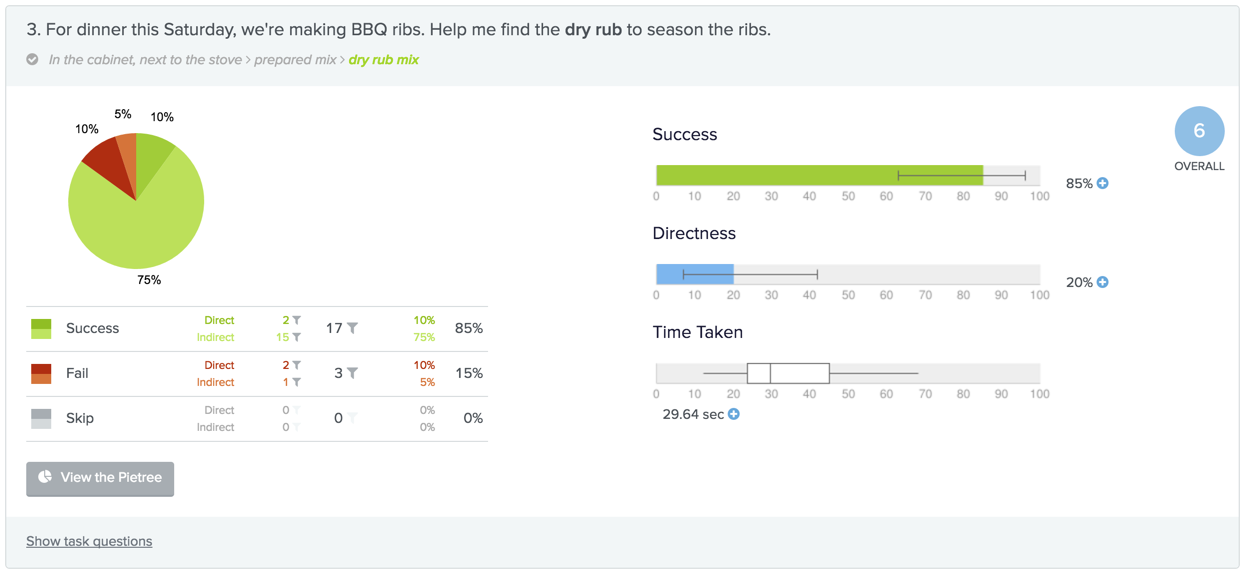

Tree testing generates a few key performance indicators to keep in mind:

- Overall score

- Task success rate

- Task directness rate

- Time taken per task

Overall score

The overall score is a weighted average of task success and directness. TreeJack founder Dave O’Brien says that an aggregate score of 8 or above for a task means that no changes need to be made (source). Lower scores indicate that it is an area that requires attention. When you start analyzing your tree test results, be sure to focus on the lower scores.

Both rounds of testing tell me that I need to focus on where to put the dry rub spices, custard powder, and that bag of chia seeds. You’ll read about that later.

Success

The success score refers to the percentage of participants who selected a correct answer, regardless of whether or not they had to jump around the tree a few times before doing so. A success score of around 80% or more is considered a good score for a task, says Optimal Workshop.

There is an overall success score across all the tasks in each round as well as for each task. Round 1 scored 91% overall and Round 2 fared a bit better (95%). Good job, Grace, good job. But the Asian in me asks why it’s not 100%. How can we make it 100%?

Directness

The directness score is the percentage of participants who did not backtrack at all when selecting an answer, whether their answer was correct or incorrect. It attempts to measure how confident participants were in selecting their answer, though it’s important to not assume too much about what participants were thinking.

Between round 1 and round 2, it appears that fewer participants (58%) backtracked in Round 2 before reaching the correct answer as compared to round 1 (54%).

Time taken

Time taken is a box plot showing the time taken for participants to complete the entire survey (in minutes) as well as per task (in seconds). In the kitchen, time is of essence when you have stuff on the stove. My mom doesn’t measure out ingredients ahead of time; she measures by eye, something I’ve also noticed my father, in-laws, and friends do.

I set the first task about finding salt to be the training question, an easy one so participants would be able to see how the test is run and know what to expect for the other questions.

Analyzing the results: focusing on the problem areas

Overall, both tree tests showed that people are in fact able to navigate my kitchen pretty well. Sure, there were a few hiccups *ahem, chia seeds, dry rub, custard powder, coconut milk*, but almost everyone was able to come their tasks successfully.

Based on the overall score, I know that I should focus on any task that scored lower than 8, so that leaves us with chia seeds, dry rub, custard powder, and coconut milk. I know that directness is lacking, so how can I improve on that?

Looking for chia seeds

Finding chia seeds for my breakfast smoothie was probably not the best task to use.

- Not many people know what chia seeds are used for.

- There are many things that chia seeds can be used in (baked goods and beverages, to name two).

- How would I manage user expectations for chia seeds as a food or nut item, not associated with drinks and beverages?

In fact, more than half of the participants (53%) indicated that finding chia seeds was a fairly difficult to very difficult task.

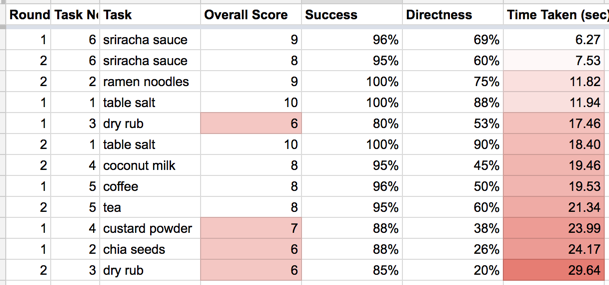

If you look at the pietree, you’ll see that people eventually looked everywhere they could. The green lines indicate the expected paths. The thicker lines indicate the popularity of that path. More than three-quarters searched the pantry first; 19% peeked in the refrigerator. Eventually I decided to place this in the pantry with flaxmeal, seeds, and nuts, which I also mix into breads and muffins.

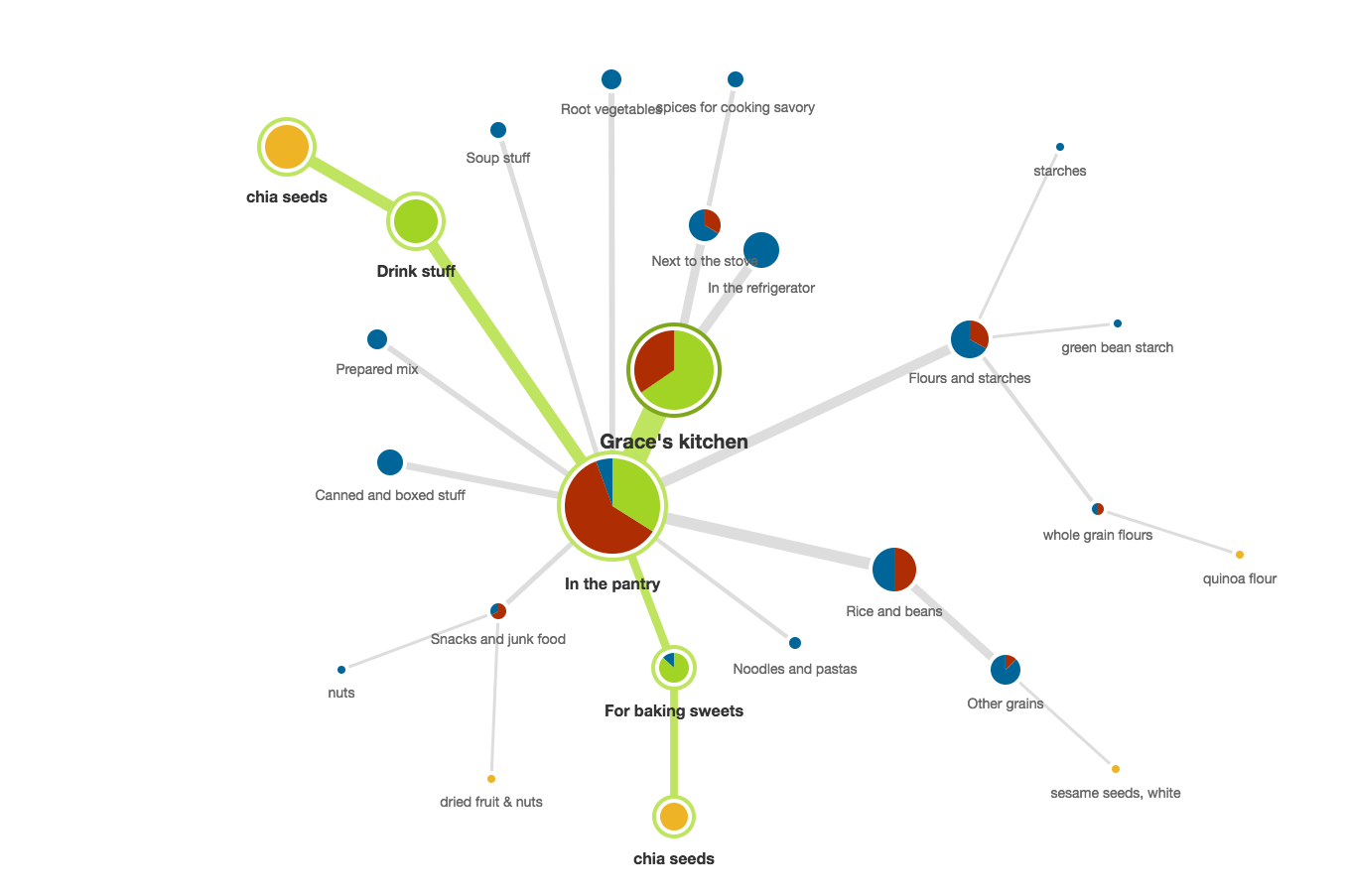

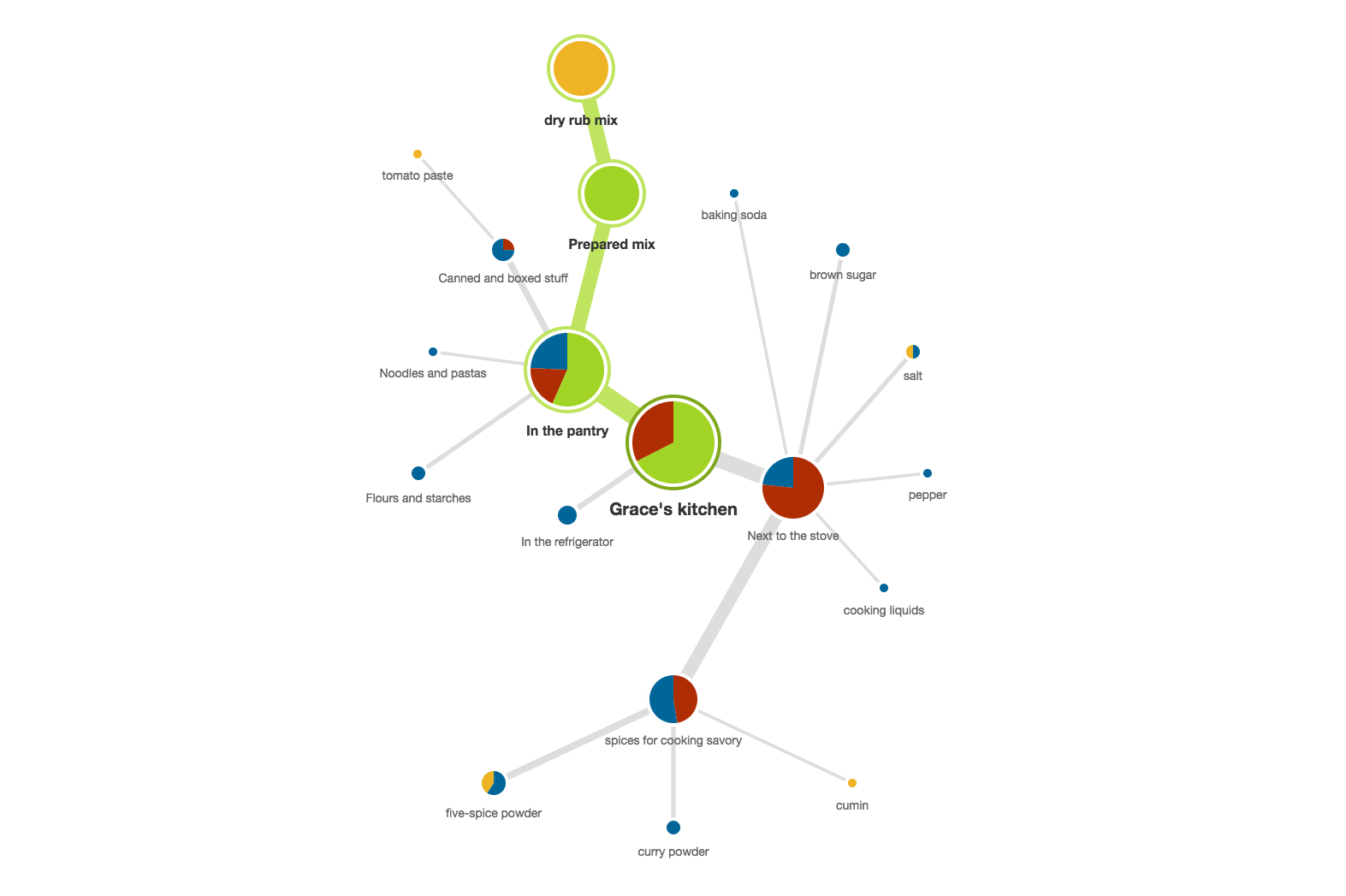

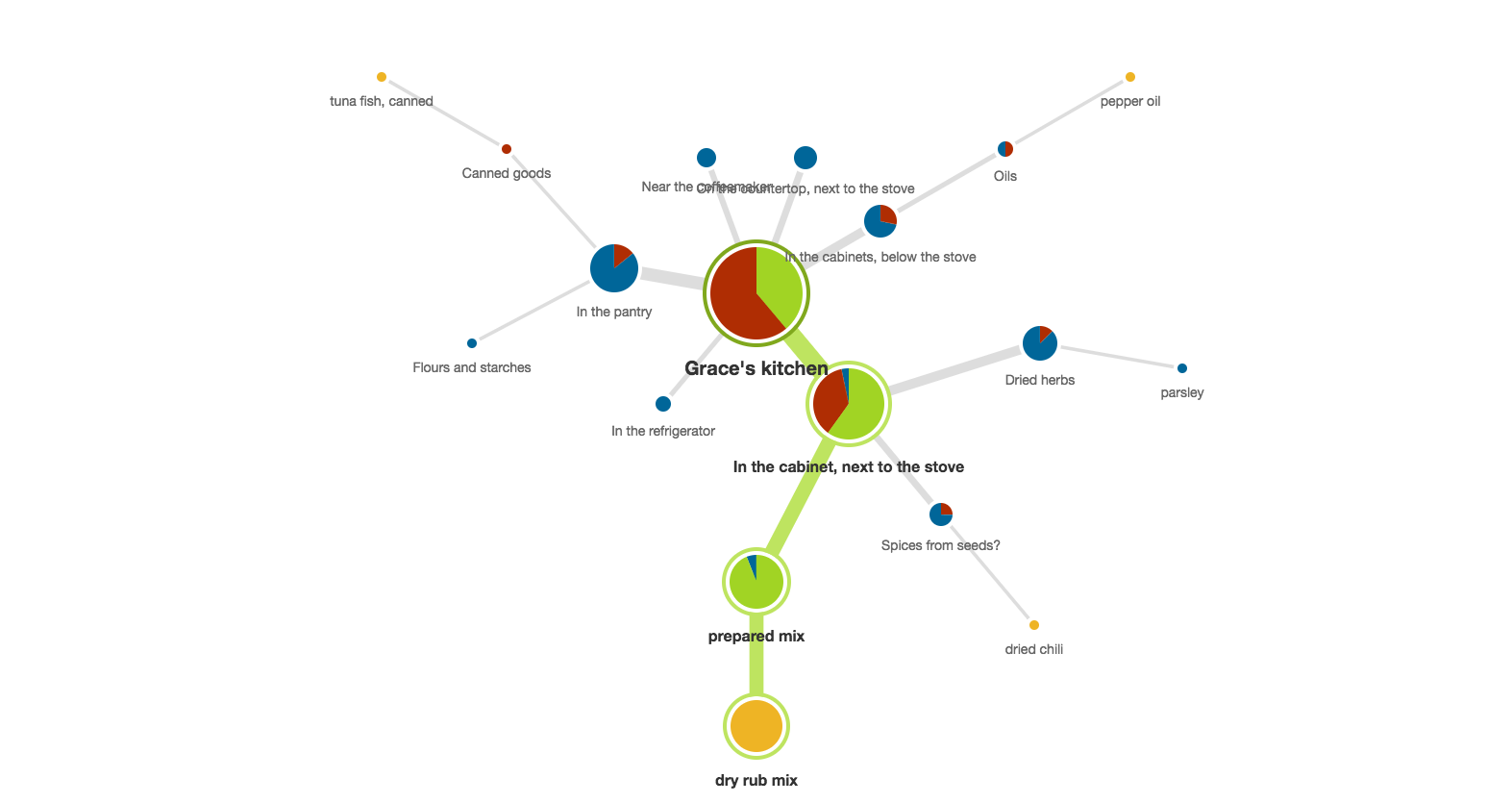

Getting the dry rub for the ribs

What’s a summer without a BBQ? Dry rub was a task that I kept in both rounds. Could you tell that I was having trouble trying to figure out where this belonged?

Refer to the pietree below. The assumed correct path is the one highlighted in green. About 88% of participants went to the pantry first, before looking around the stove.

In round two, I designated more areas around the stove for spices (for cooking savory dishes). While not the first place they went to (55% went to the pantry first), almost everyone (90%) looked in the cabinet next to the stove during the task. Even though more participants were able to find where it was stored, it took them 70% more time to find it.

In the end, I’ve opted to keep all savory spices next to the stove. Additional contextual inquiry will help inform how that decision will hold up. Cue observing in-laws putting groceries away in the kitchen.

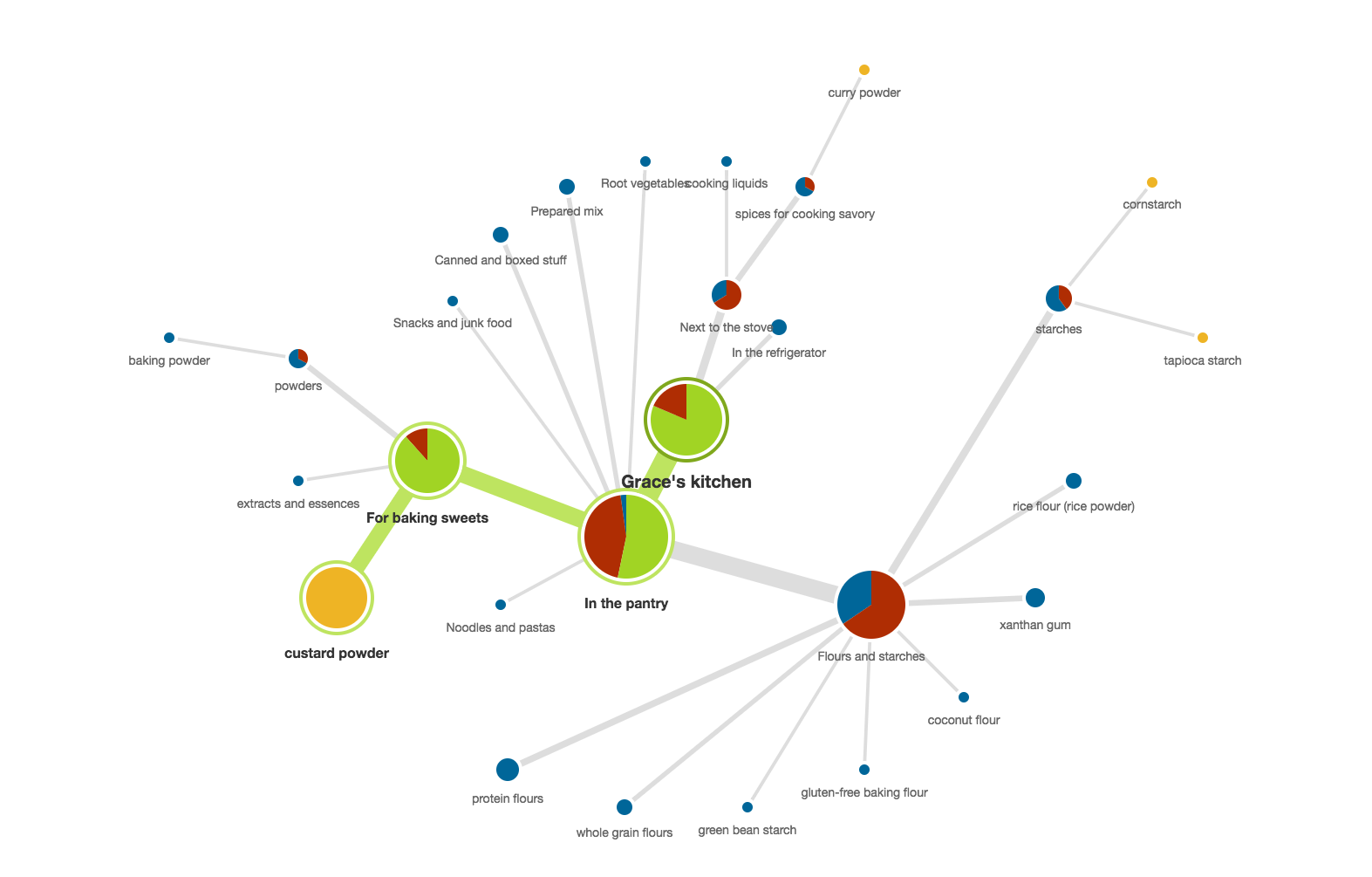

Is it a flour? Is it a starch? No, it’s custard powder!

Let’s talk about custard powder! Lots of participants commented that they had no idea what custard powder is (note that all the test participants are from the United States). According to Wikipedia, it is popular in the United Kingdom for making custards—also known as pudding—without eggs.

Some indicated that they’d consider it a flour and looked for it near the flour section. Some thought that it would be classified with other “powders.” To be honest, I wasn’t sure either and left this for you to best tell me where to store it. Eventually, I kept it with the rest of the baking powders and I haven’t had an issue with finding it yet.

So what’s the verdict?

Every taxonomy is subject to stakeholder drama and idiosyncrasies. In a kitchen, this is dictated by the physical layout and its workflows and even colloquial nuances in understanding terminology. What evolves as a stable enough navigation for my kitchen won’t necessarily work for yours.

Here’s what you can get out of this tree test:

- Assess the existing navigation. Be sure to start first by tree testing your navigation. You’ll find out where your trouble areas are and how it compares against your proposed sitemaps.

- Oh, and when deciding on the tasks, be sure to focus on common tasks and not so much on the outliers and special cases.

- Opt for more overlapping tasks if possible and especially if you’re planning on iterations. Having the same tasks that appear in both iterations helps set benchmarks. In the end, I only had three overlapping tasks: salt, dry rub, and sriracha sauce.

No one had trouble at all with finding salt, sriracha sauce, and coffee, so it’s not worth the time to fix what’s not broken.

- At the the same time, it’s important to identify the problem areas. Dry rub, coconut milk, and custard powder were definitely outliers and worth digging deeply into.

- Minimize variables between iterations. Try not to change the wording too much. You want to be sure that you can pinpoint how much effect the change in the navigation structure has and not worry about how the wording has affected the task. Dry rub was one I introduced more than one variable. I changed the wording in the task. I changed where it lived in the taxonomy. How would I know which variable attributed to the higher success?

Epilogue

I took some time after the tree test ended and implemented some of the changes that folks recommended. I created a “drink and beverage” station with cups and coffeemaker and hot water kettle nearby on the kitchen counter. I rearranged where we kept plates and rice bowls. My husband and son had a quick introduction to the new arrangement before the in-laws came back.

Then the in-laws returned from their six-month sabbatical, and I’ve had a fair amount of time (about five months since I conducted this tree test) to observe their interactions in the kitchen. My parents have also been over to conjure up more meals since I’ve executed the new taxonomy.

The good news?

- Spices next to the stove are easier to spot.

- Sriracha, XO sauce, and hoisin sauce now have a dedicated spot in the refrigerator door.

- New dedicated section was added in the pantry for nuts, including chia seeds.

- The “flours and starches” area now has separate sections for wheat flour, gluten free flours, starches, yeast, and powders (including custard powder)

The bad news?

- Sugar moves back and forth between the small jar next to the stove to the pantry where there’s a whole section devoted to “sugar and honey.”

- Sesame seeds are hard to find. It’s a topping really, not cooked as a grain or nut.

- Because they’re used for the same purpose (thickening), sweet potato starch, cornstarch, and tapioca starch could be combined in one container. I shook my head so hard on this one.

Now that this taxonomy is working for most of my users, it’s time to turn my attention to governance—maintaining the integrity of this taxonomy and creating rules for adding new taxonomy concepts and removing obsolete or outdated ones.

This series started out as a justification of why taxonomy should be an essential part of a website redesign, and for this instance, of a kitchen reorganization. If you’re wondering how we got here, check out what I’ve been doing in my kitchen.

- Building the business case for taxonomy

- Planning a taxonomy

- The many facets of taxonomy

- Card sorting

- Tree testing

- Taxonomy governance

- Best practices of enterprise taxonomies

References

- Dave O’Brien “Tree Testing“

- Dave O’Brien “Tree testing in the design process — Part 1: The research phase”

- Dave O’Brien “Tree testing for websites” – a comprehensive guide

- Jeff Sauro “Using Tree-Testing to Test Information Architecture“

- Kirbie’s Cravings. Hong Kong Egg Waffles

One comment

Comments are closed.