This is part 2 of “Taxonomy of Spices and Pantries,” in which I will be exploring the what, why, and how of taxonomy planning, design, and implementation:

- Building the business case for taxonomy

- Planning a taxonomy

- The many facets of taxonomy

- Card sorting

- Tree testing

- Taxonomy governance

- Best practices of enterprise taxonomies

In part 1, I enumerated the business reasons for a taxonomy focus in a site redesign and gave a fun way to explain taxonomy. The kitchen isn’t going to organize itself, so the analogy continues.

I’ve moved every couple of years and it shows in the kitchen. Half-used containers of ground pepper. Scattered bags of star anise. Multiple bags of ground and whole cumin. After a while, people are quick to stuff things into the nearest crammable crevice (until we move again and the IA is called upon to organize the kitchen).

Planning a taxonomy covers the same questions as planning any UX project. Understanding the users and their tasks and needs is a foundation for all things UX. This article will go through the questions you should consider when planning a kitchen, er, um…, a taxonomy project.

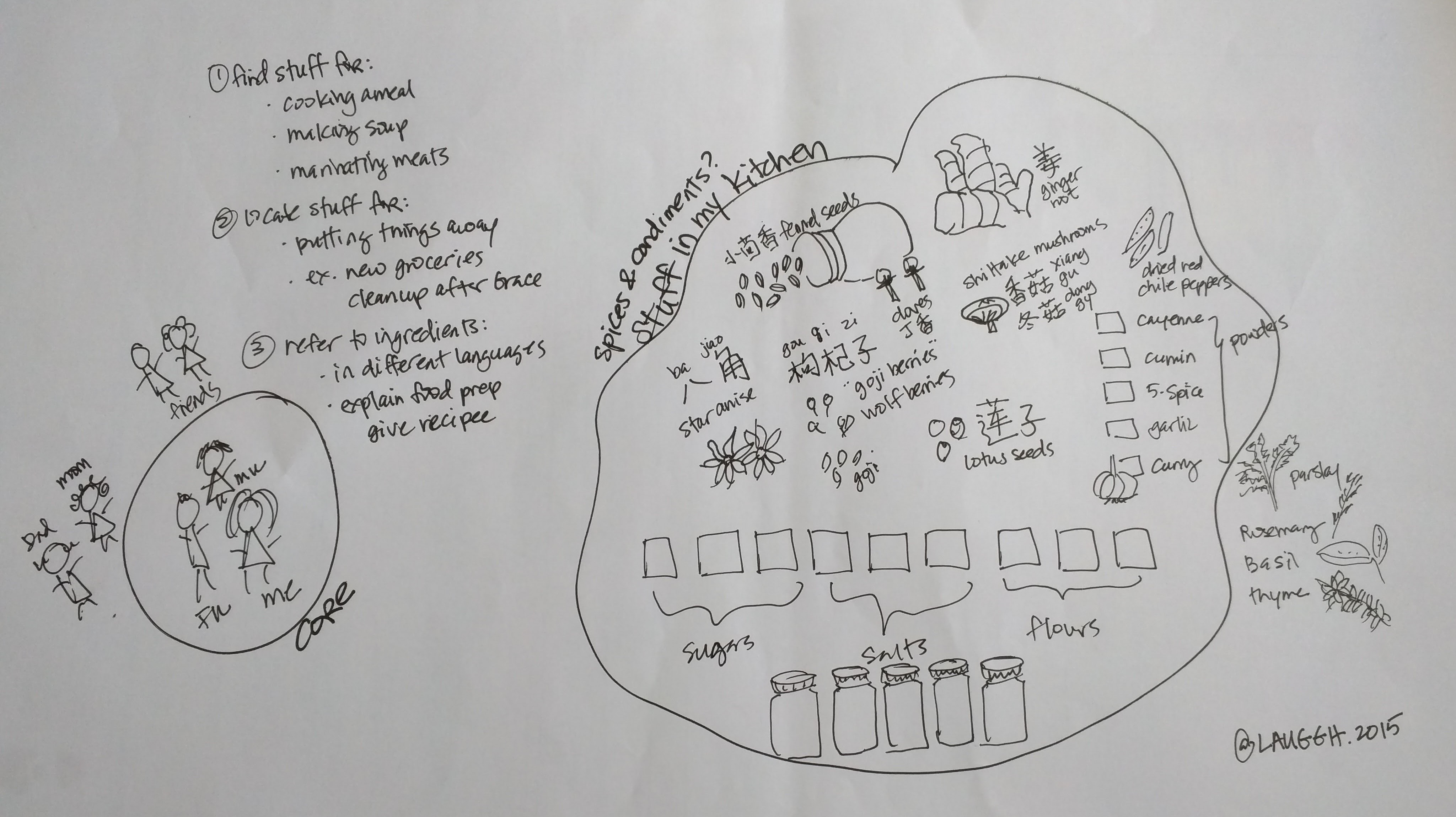

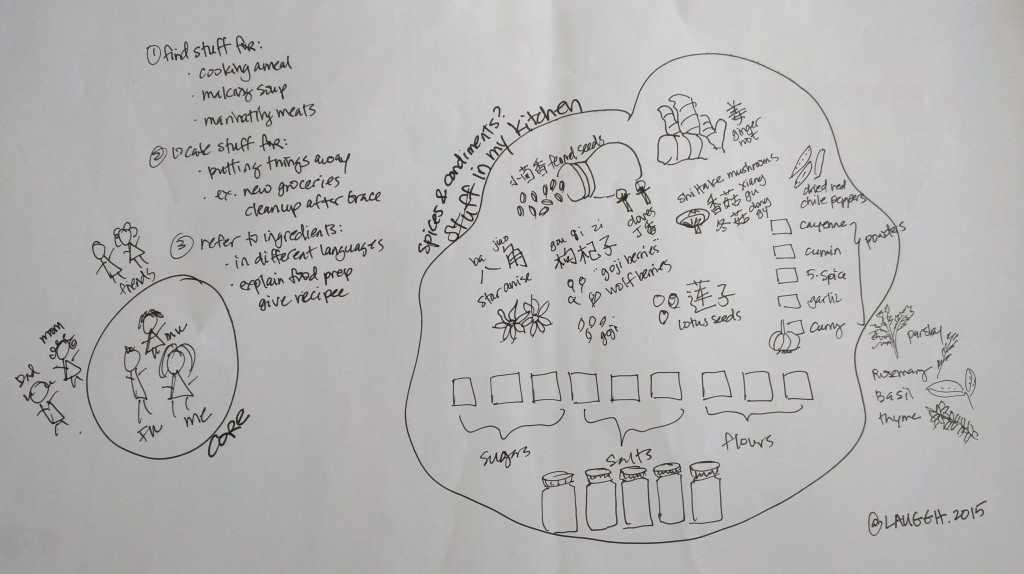

Same as a designing any software, application, or website, you’ll need to meet with the stakeholders and ask questions:

- Purpose: Why? What will the taxonomy be used for?

- Users: Who’s using this taxonomy? Who will it affect?

- Content: What will be covered by this taxonomy?

- Scope: What’s the topic area and limits?

- Resources: What are the project resources and constraints?

(Thanks to Heather Hedden, “The Accidental Taxonomist,” p.292)

What’s your primary purpose?

Why are you doing this?

Are you moving, or planning to move? Is your kitchen so disorganized that you can’t find the sugar you needed for soy braised chicken? Is your content misplaced and hard to search?

How often have you found just plain old salt in a different spot? How many kinds of salt do you have anyway–Kosher salt, sea salt, iodized salt, Hawaiian pink salt? (Why do you have so many different kinds anyway? One of my favorite recipe books recommended using red Hawaiian sea salt for kalua pig. Of course, I got it.)

You might be using the taxonomy for tagging or, in librarian terms, indexing or cataloging. Maybe it’s for information search and retrieval. Are you building a faceted search results page? Perhaps this taxonomy is being used for organizing the site content and guiding the end users through the site navigation.

Establishing a taxonomy as a common language also helps build consensus and creates smarter conversations. On making baozi (steamed buns), I overheard a conversation between fathers:

Father-in-law: We need 酵母 [Jiàomǔ] {noun}.

Dad: Yi-see? (Cantonese transliteration of yeast)

Father-in-law: (confused look)

Dad: Baking pow-daa? (Cantonese transliteration of baking powder)

Meanwhile, I look up the Chinese translation of “yeast” in Google Translate while mother-in-law opens her go-to Chinese dictionary tool. I discover that the dictionary word for “yeast” is 发酵粉 [fājiàofěn] {noun}.

Father-in-law: Ah, so it rises flour: 发面的 [fāmiànde] {verb}

This discovery ensues more discussion about what it does and how it is used. There was at least 15 more minutes of discussing yeast in five different ways before the fathers agreed that they were talking about the same ingredient and its purpose. Eventually, we have this result in our bellies.

Who are the users?

Are they internal? Content creators or editors, working in the CMS?

Are they external users? What’s their range of experience in the domain? Are we speaking with homemakers and amateur cooks or seasoned cooks with many years at various Chinese restaurants?

Looking at the users of my kitchen, I identified the following stakeholders:

- Content creators: the people who do the shopping and have to put away the stuff

- People who are always in the kitchen: my in-laws

- People who are sometimes in the kitchen: me

- Visiting users: my parents and friends who often come over for a BBQ/grill party

- The cleanup crew: my husband who can’t stand the mess we all make

How do I create a taxonomy for them? First, I attempt to understand their mental models by watching them work in their natural environment and observing their everyday hacks as they complete their tasks. Having empathy for users’ end game—making food for the people they care for—makes a difference in developing the style, consistency, and breadth and depth of the taxonomy.

What content will be covered by the taxonomy?

In my kitchen, we’ll be covering sugars, salts, spices, and staples used for cooking, baking, braising, grilling, smoking, steaming, simmering, and frying.

How did I determine that?

- Terminology from existing content. I opened up every cabinet and door in my kitchen and made an inventory.

- Search logs. How were users accessing my kitchen? Why? How were users referring to things? What were they looking for?

- Storytelling with users. How did you make this? People like to share recipes and I like to watch friends cook. Doing user interviews has never been more fun!

What’s the scope?

Scope can easily get out of hand. Notice that I have not included in my discussion any cookbooks, kitchen hardware and appliances, pots and pans, or anything that’s in the refrigerator or freezer.

You may need a scope document early on to plan releases (if you need them). Perhaps for the first release, I’ll just deal with the frequent use items. Then I’ll move on to occasional use items (soups and desserts).

If the taxonomy you’re developing is faceted—for example, allowing your users to browse your cupboards by particular attributes such as taste, canned vs dried, or weight—your scope should include only those attributes relevant to the search process. For instance, no one really searches for canned goods in my kitchen, so that’s out of scope.

What resources do you have available?

My kitchen taxonomy will be limited. Stakeholders are multilingual so items will need labelling in English, Simplified Chinese, and pinyin romanization. I had considered building a Drupal site to manage an inventory, but I have neither the funding or time to implement such a complex site.

At the same time, what are users’ expectations for the taxonomy? Considering the context in the taxonomy’s usage is important. How will (or should) a taxonomy empower its users? It needs to be invisible; as an indication of a good taxonomy, it shouldn’t affect their current workflow but make it more efficient. Both fathers and my mom are unlikely to stop and use any digital technology to find and look things up.

Most importantly, the completed taxonomy and actual content migration should not conflict with the preparation of the next meal. My baby needs a packed lunch for school, and it’s 6 a.m. when I’m preparing it. There’s no time to rush around looking for things. Time is limited and a complete displacement of spices and condiments would disrupt the high-traffic flow in any household. Meanwhile, we’re out of soy sauce again and I’d rather it not be stashed in yet a new home and forgotten. That’s why we ended up with three open bottles of soy sauce from different brands.

What else should you consider for the taxonomy?

Understanding the scope of the taxonomy you’re building can help prevent scope creep in a taxonomy project. In time, you’ll realize that the 80% of your time and effort is devoted to research while 20% of the time and effort is actually developing the taxonomy. So, making time for iterations and validation through card sorting and other testing is important in your planning.

In my next article, I will explore the many uses of taxonomy outside of tagging.