At the time of this writing, a search for UX design jobs on job finder Glassdoor reveals almost 20,000 open positions in the United States alone. By another source, the number is 24,000, with a 22% projected growth rate in the next ten years.

At the time of this writing, a search for UX design jobs on job finder Glassdoor reveals almost 20,000 open positions in the United States alone. By another source, the number is 24,000, with a 22% projected growth rate in the next ten years.

Salaries vary between USD$60,000 to $127,000 annually, with the median salary for 2017 being $77,000. With a significant spike year-to-year, the median salary in 2018 is $93,000 in the States, with the coasts offering the highest paying positions.

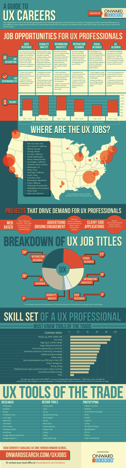

Onward Search provides a useful overview of the UX design job market in infographic format.

If we go by the stats, the market for UX designers could not be hotter. And, yet, those at the forefront of the field are rapidly calling 2018 the beginning of the end for the UX design job title.

Have we reached peak UX design already? Is it at the maturity stage in the life cycle?

And if it is, what’s next?

Looking at the future

From “webmaster” to “information architect” to “interaction designer” to “UX designer,” we have always been able to adapt what we do in response to changing needs. Where is the future-minded designer headed now? What will the new and improved designer shape-shift into for the future?

Most companies and start-ups today have dedicated UX roles and titles that struggle to keep up with a designer’s actual work. The reliable way, therefore, to see what designers do is to analyze what they are busy doing, not the titles they hold at slow-to-change enterprises.

According to a freshly released trends report by the UX Design Collective,

- “Some designers are adventuring in new fields and technologies, like virtual reality, conversational design, voice interfaces;

- Some are focusing on more specific areas of the design craft, like motion design, prototyping, and UX writing;

- Some are updating their titles to product designers, broadening their scope beyond interaction design to focus more on product strategy and business.”

The report goes on to make one of the most decisive statements about the distinction between art and design by flatly stating zero correlation:

“It’s about time we accept the fact we are not artists and embrace being part of a business. For the best.”

Well, there’s the end to that decades-long debate!

The role of the design school

Many UX designers are self-taught, never having studied the subject in school. Does this mean anyone can become a UX designer? Not so, says Rosie Allabarton at UX Mastery. She calls the accessibility of the profession a myth and continues by saying:

“Not everyone can work as a UX designer. Why? Because working in UX requires you to not only LOVE people, but to be endlessly curious about why they do the things they do. If you’re not a people-person, and you have no curiosity about human behaviour, then this simply isn’t the career choice for you. Sorry!”

A designer needs to be a people-person now? That is quite far away from the usual (and unfair) stereotype of the designer as the introverted creative type slaving away alone on a computer or in a studio.

Allabarton’s requirements for a UX designer—empathy, curiosity, and communication—don’t necessarily require a visual arts education. An anthropologist or anyone in the liberal arts could exercise these skills just as well as someone who studied graphic design. Although graduating from a design program makes the most sense for students pursuing a career in UX design, many also enter the profession from related fields that provide students with an understanding of areas relevant to design like psychology, (increasingly) writing, or computer technology. According to Maryville University, for instance, studying software development can be a solid foundation for a career as a UX designer.

However, if the UX Trends list in the previous section is an accurate representation of the professional activities of the designer today, one may argue that these are the very areas design schools should actively be providing instruction in. Instead of looking just at what has been, academia should be a place for looking forward and preparing the future generation for tomorrow’s challenges.

A look at educational institutions, however, represents a far less clear picture, with schools caught between the old and the new, frantically trying to update traditional design curricula in response to a rapidly changing market while still trying to foster a sense of design history, context, and skill-based foundation in their students.

Though there may be many different formal education tracks for a career in UX (including certifications and distance learning in related fields like graphic design and software development), thousands of students still go to design schools every year for a traditional undergraduate degree.

The QS Top Universities ranking lists Parsons School of Design, Rhode Island School of Design, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology as the top three art and design universities in the United States.

Of these, only the first two offer dedicated design programs that also provide instruction in UI/UX: Parsons through its Design and Technology and Communication Design programs and RISD via its quite traditionally titled Graphic Design offering.

Another school in the top ten, Carnegie Mellon, offers both a regular design program as well as a Human-Computer Interaction Masters that specializes in UI and UX.

What I learned in design school

I myself attended the MFA in Design and Technology program at Parsons, an open-ended design program in which my peers and I were free to work on any art and design project with, ideally, a technology component to it. This meant I was working on designing and creating a transmedia storyworld while my peers developed everything from fashion-tech to mobile apps and mixed reality projects.

One course that stands out as an example of bridging the academic divide between design and business is the Luxury Design and Strategy course in collaboration with Columbia Business School. Design students from Parsons were teamed up with business students at Columbia to work on actual projects from heavyweight companies in the luxury industry such as Hermes, Van Cleef and Arpels, and Ferragamo. The course provides ample opportunity for cross-disciplinary collaboration and project work that reflects real business challenges.

While some of my peers would have preferred at least one intensive course on UX design and a more skill-based one like “mobile app design,” there were always opportunities to explore the subject in a variety of different courses (whether they were titled “Building Worlds” or “Interactive Design for Museums”). A graduate program is more about developing an understanding of critical issues and creating original work and less about doubling as a trade school workshop.

Evaluating my Parsons experience in terms of the three-pronged design activity cited above, I would say it scored highly on the first (new fields and technologies) with signs of progress in the third (product design and business strategy) while somewhat lacking in the second (specialized areas of the design craft), at least at the graduate level. It was the student’s responsibility altogether to take the initiative to register in certain electives and workshops that could provide skill training.

Elective coursework works well for the self-directed student or one who has studied or worked in design earlier. However, for many who enter from outside the field, it can lead to a gap between their academic training and the needs of the market they will be entering upon graduation. As is the case for most designers, their actual training in UX still comes from learning on the job and/or through freelance client work.

Where does UX design go from here?

The future of design beyond 2018 is, perhaps, best predicted by looking at what young students are doing while they’re still in school, and freely thinking, exploring, experimenting and creating.

A review of a recent thesis show provides a good look at the result of design engagement over the course of two years by the graduating class. The categories include:

- VR/MR/AR

- Installation

- Playful experiences

- Storytelling/Film

- Culture/Issues

- Speculative/Critical

- Product design

- Education

- Wearable

UX design is not a category in itself, but it plays a role in all of the above. For designers today, UX design is a given—merely a means to a bigger end, whether its a product or any manner of creative exploration.

What do you envision for the future of a UX design education and career? Let us know in the comments below.

Hi. Could you fix the external links, please? Thank you.

Thank you, Manu. The links are fixed now.

Link to “Onward search” = ?

Thx 🙂

It’s back in the article but here’s a direct link: http://www.onwardsearch.com/career-center/ux-careers-guide/

Thank you. Link under the graphic still wrong for me.

(And replying here is _very_ light grey text on white background).

Thanks for catching that. That link is fixed too now.

Thank you 🙂

Thank you for sharing this infographic. However, I was a little surprised to see the whole bunch of outdated tools under UX Tools of the Trade, but nothing like Sketch, Adobe XD for UX design and prototyping, not to mention InVision. Maybe, it’s not for 2018? got to be 2015 then.

Thank you for your comment, Alla. Onward Research does have a report for 2018 (https://www.onwardsearch.com/digital-creative-salary-guide-2018/) but you have to sign up to view it. It apparently includes new salary figures but doesn’t mention any tools so thank you for listing Sketch, Adobe XD and InVision.

I came to know about the field of UX design through my degree in Information Studies (formerly Library and Information Science), but I am not sure that many people make the transition from library and information science programs to UX design, since some of the pieces — information architecture, usability, etc. — are there but at least at my institution the design component is completely absent.

Thanks For Sharing This Article, Your Good obatkuatbatam.com

There are many of us experienced (aka, “old”) designers who have a ton of hard-won people skills, understand business, and have backgrounds in the social sciences, in addition to design and UX design experience. What we apparently lack is the right decade on our birth certificate. Employers want all the soft skills that come with experience but in a 30-something package.

Thank you for sharing, Anne. Ageism is definitely a problem and we appreciate you highlighting it.

Thank you for the great article and insights! I’m curious as to how other top design schools around the world are doing in educating student designers in terms of UX education.

Thank you, Evangeline. And yes, I would also be very interested in analyses of design schools worldwide. Hopefully some readers will be able to share their relevant experiences.

I have a psychology degree and while I’ve enjoyed almost a decade in UX career, I’ve noticed that it’s very difficult for students to prepare themselves via most psychology programs. For me, I had a side gig of making websites throughout college, and a creative director in my first job who helped me transition into UX from a front-end job. Most psych programs are just too focused on getting their students into academic research or mental healthcare jobs. It’s hard to make the connections between psych research and design on your own if your own professors can’t. If design programs are struggling to keep their curricula relevant, I can’t expect the social sciences to even try.

Thank you for sharing that insight, Dez. The educational challenges you highlighted are definitely significant. Would you say that your psychology background helps you in implicit and explicit ways in your UX work, and to what extent? Would you have preferred to have a traditional design education instead? I’m sure our readers (and I) would appreciate knowing about your experience, if you feel comfortable with sharing. Thank you!

Really loved your writing as always, very insightful and inspiring! Looking forward for more!

Thank you, Zeqing. I appreciate it. 🙂

La création de sites internet, c’est notre métier.