Did you ever get bounced around between departments when interacting with a company or service? This happened to me recently with my credit card: the card issuer and the bank backing it seemed to disagree who was responsible for my problem. Each blamed the other. I got caught in the middle.

My communication with them also crossed multiple channels. For some things I used their website, for others I had to call. There were emails, regular mail and even a fax involved as well. None of it seemed coordinated. Apparently it was my job to piece it together. Bad experience.

Why does this happen? All too often companies are focused on their own processes, wrapped up in a type of organizational navel gazing. They simply don’t know what customers actually go through.

What’s more, logical solutions can cross departmental lines. Ideal solutions may require crossing those boundaries. An organization’s rigid decision making makes that difficult.

Here’s where I believe IAs and UX designers can use our skills to make a difference. We have the ability to understand and to map out both business processes and the user experience. Visual representations can provide new insight into solutions that appeal to a range of stakeholders. Alignment diagrams are a key tool to do this.

Mapping The Experience

Alignment diagrams reveal the touchpoints between a customer and a business. Illustrating these helps a company shift its inward-focusing perspectives outward. Alignment diagrams make the value creation chain visible.

The phrase “alignment diagrams” describes a class of documents that reveal the touchpoints between a customer and a business. These touchpoints are organized and visually aligned in a single graphical overview. Illustrating these touchpoints helps a company shift its inherently inward-focusing perspectives outward. Alignment diagrams make the value creation chain visible from both sides of the fence.

Alignment diagrams are not new. In fact, you’ve already used them. Thus my definition of alignment diagrams does not introduce a new technique but rather recognizes how existing techniques can be seen in a new, constructive way.

Alignment diagrams have two major parts. On the one side, they illustrate various aspects of user behavior—actions, thoughts, and feelings, among other aspects of their experience. On the other side, alignment diagrams reflect a company’s offerings and business process in some way. The areas where the two halves meet gives rise to touchpoints, or the interactions between customers and an organization.

Below are examples of two diagrams that illustrate the alignment principle.

Example 1: Service Blueprint

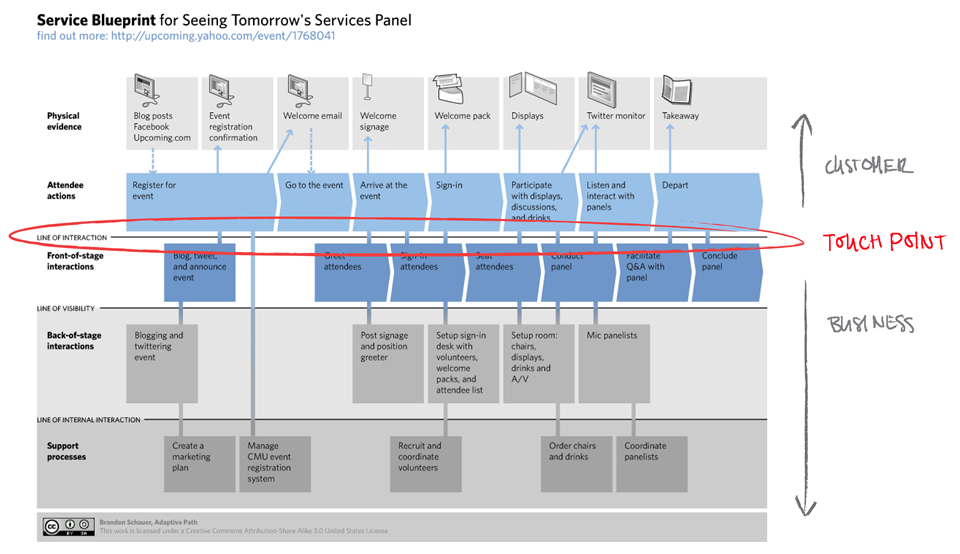

The first example is a service blueprint created by Brandon Schauer of Adaptive Path (Figure 1.). This shows the chronological flow of steps for attending a live event, in this case a panel on service design. (See the original details of the event from 2009 [1]).

The top two rows show the phases and physical devices a participant might use. We can call this the “front stage.” The bottom three rows show the activities of the organizer. These are “backstage” activities. These two parts are separated by the “line of interaction,” or touchpoints between participants and organizer of the event.

Figure 1: An example of a simple service blueprint by Brand Schauer, Adaptive Path

Example 2: Mental Model Diagram

The next example of an alignment diagram is a mental model. Indi Young developed this technique and detailed it in her book Mental Models (Rosenfeld Media, 2008) [2].

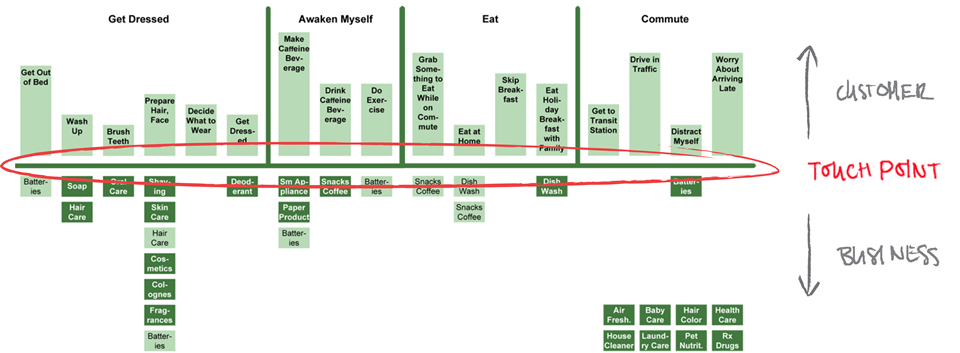

Figure 2 is a slightly simplified version of a mental model diagram, but it shows the alignment principle well. This example shows a mental model for activities related to “getting up in the morning.” The top half hierarchically arranges user actions, thoughts and feelings gleaned from primary research. These are clustered together into broader “goal spaces” (e.g., “Get Dressed”).

Below the center horizontal line are products and services that support people in these activities. With this alignment, providers of goods and services can see where they address user needs and where there are gaps.

Figure 2: An example of a mental model diagram by Indi Young, reflecting the alignment principle.

There are other visual styles and approaches to alignment diagrams beyond the above figures. (See the list of Alignment Diagram resources at the end of this article.) Customer journey maps and workflow diagrams are also examples. So there is no single approach to the alignment technique. Instead, you choose the form, the information included, and the way you present them to shape your overall message. It depends on your situation. The important thing to remember is that an alignment diagram shows user behavior aligned to business activity to reveal touchpoints.

Locating Value

An analysis of the touchpoints between users and the business lets us see value creation from both sides of the equation at the same time. This is at the core of the alignment technique.

Businesses ultimately need to earn money. But to do so they also have to provide some value to customers. An analysis of the touchpoints between users and the business lets us see value creation from both sides of the equation at the same time. This is at the core of the alignment technique.

In a previous Boxes and Arrows article entitled “Searching for the Center of Design,” Jess McMullin proposes what he calls “value-centered design.” [3] Instead of focusing solely on the business or solely on users, Jess advocates focusing on how value is created for both. “Value-centered design” is the approach he prefers. He writes:

The basic premise of value-centered design is that shared value is the center of design. This value comes from the intersection of: business goals and context, individual goals and context, and the offering…and delivery.

Value-centered design starts a story about an ideal interaction between an individual and an organization and the benefits each realizes from that interaction.

Jess McMullin, “Searching for the center of design”, Boxes and Arrows, 2003.

Alignment diagrams let us tell the story of value creation.

Once completed, alignment diagrams serve as diagnostic tools. With them we can spot and prioritize areas for improvement. They also point to opportunities for innovation and growth. Ultimately, alignment diagrams let designers capture and reflect how value is created in a holistic way. When communicated to decision makers, this can have real business impact by changing the focus from how products are made to the experience customers have.

Who Creates Alignment Diagrams?

Modern business challenges are wicked problems. Organizations unknowingly pass this complexity on to customers, resulting in negative user experiences. Alignment diagrams can reduce complexity for both customers and for organizations. They are an antidote to the challenges our business partners face.

The good news is you probably already have the skills needed to create alignment diagrams. These include:

1. Conducting Research

Alignment diagrams are not made up. They are based on real data. Face-to-face interviews and observation work best. This includes contacting people on the business side: stakeholder research is part of the alignment technique.

2. Synthesizing Findings

Designers are good at describing abstract concepts, such as an intended experience. We’re able to empathize with users and summarize their perspective well. And we can communicate this back to our business partners in a way they can understand.

3. Visualizing Information

Alignment diagrams are visual stories. Designers are good at representing ideas in graphic form. The visual nature of alignment diagrams makes them compact and immediately understandable.

4. Brainstorming

Alignment diagrams serve as an excellent stimulus for a workshop or brainstorming session. Designers have the skills to creatively brainstorm and lead such sessions.

5. Prototyping Solutions

Exploring different directions is a key aspect of “design thinking.” Designers are well-versed in trying out different options—from sketching to wireframing to prototyping.

Keep in mind that the lines between design-related disciplines are blurring. Service designers increasingly use online services and digital kiosks in their concepts. UX designers must be able to integrate offline support and services into their solutions. IAs need to be able to structure information across channels, including physical spaces. Interaction designers must conceive of workflows and actions across media types and devices.

In the end, alignment diagrams aren’t the domain of one field or the other: they can inform any field. The skills needed to create them, listed above, cross these lines as well.

Getting Started

Alignment diagrams start a conversation towards coherence, bringing actions, thoughts, and people together to foster consensus. More importantly, they focus on creating value—for both the customer and the business.

Understanding the mechanics of alignment diagrams is fairly straight forward. The hard part is getting your foot in the door. Often designers aren’t called in until after a project is already set up. Alignment diagrams, however, really need to impact decisions much earlier in the process—before a project even starts. This means you need to “swim upstream” and reach out to a potentially new set of stakeholders.

For designers in internal teams, you may have access to managers, product owners and other executives who could benefit from alignment diagrams at a strategic level. For external consultants, pitching a case for an alignment diagram effort may be harder: reaching high-level decision makers is difficult. Either way, you’ll need to effectively evangelize alignment diagrams in order to get the time and money to complete one.

Here are some things you can do to get started:

1. Learn about alignment diagrams.

Start by reading books like Indi Young’s Mental Models. Or, check out things like my resources on customer journey mapping on the web [4]. I also have a presentation [5] and an article [6] coauthored with Paul Kahn specifically on alignment diagrams.

2. Sketch draft diagrams for your current project.

What story could you tell on your current project to show where customer value and business value is located? How would best visualize that story in a diagram? Even without any official project scope or user research, you can sketch out a rough map showing the facets of information you’d include, where alignment occurs, and how you would visually convey your message. This is practice in understanding the alignment technique.

3. Complete an alignment diagram “under the wire.”

A formal alignment diagram must be based on real evidence. But this evidence could come from a variety of sources. A high-level customer journey map, for instance, could be created with data from existing research. Or, try adding a few simple questions your next usability test to understand users’ interaction with a service. Create a draft diagram from this data as you do other types of analysis. Present this to stakeholders. It’s likely they’ll find it interesting and ask for more.

4. Find a champion in management.

Seek out business partners who might “get” alignment diagrams. Discuss the possibility of a pilot project with them. For the cost of a normal usability test, for instance, you could create a simple alignment diagram. Unlike outcomes from other types of research, such as marketing studies or usability tests, alignment diagrams do not change very quickly. Be sure to highlight the longevity of an alignment diagram effort to sponsors, and remind them they’ll be able to refer to the information years later.

Conclusion

If you’re interested in learning more about alignment diagrams, James Kalbach has scheduled workshops in Prague and London:

- A half-day pre-conference workshop at Euro IA in Prague on Sep, 22

- A full-day workshop at UX Fest in London on Nov, 3

Keep an eye on the Boxes and Arrows Events Calendar for more.

Truth is, the business world is becoming increasingly complex. Studies in business complexity show that leaders are unable to cope: they are pulled in different directions and unable to focus [7, 8]. Modern business challenges are wicked problems. All too often, organizations unknowingly pass this complexity on to customers, resulting in negative user experiences.

While they do not guarantee success, alignment diagrams can reduce complexity for both customers and for organizations. They are an antidote to the challenges our business partners face. At a minimum, alignment diagrams start a conversation towards coherence, bringing actions, thoughts, and people together to foster consensus. More importantly, they focus on creating value—for both the customer and the business.

Designers can use their skills to map out value creation and help solve business problems. Empathizing with users and illustrating out their experiences plays a big role. Visualizing touchpoints provides an immediate “big picture” often lacking in many organizations. This can provide a much-needed shift of attention from inside-out to outside-in. Alignment diagrams are a class of documents that seek to address the causes of poor experiences at their roots and ultimately help designers have a real business impact.

[1] Brandon Schauer, Service Blueprint, http://adaptivepath.com/ideas/this-thursday-in-sf-service-design-panel-kicker-kickoff

[2] Indi Young, Mental Models (Rosenfeld Media, 2008). http://rosenfeldmedia.com/books/mental-models/

[3] Jess McMullin, “Searching for the Center of Design,” Boxes and Arrows (Sept 2003). http://www.boxesandarrows.com/view/searching_for_the_center_of_design

[4] James Kalbach, “Customer Journey Mapping Resources on the Web.” http://experiencinginformation.wordpress.com/2010/05/10/customer-journey-mapping-resources-on-the-web/

[5] James Kalbach, “Alignment Diagrams: Strategic UX Deliverables,” Euro IA Conference (Paris, 2010). http://www.slideshare.net/Kalbach/james-kalbach-alignment-diagrams-euro-ia-2010

[6] James Kalbach and Paul Kahn, “Locating Value with Alignment Diagrams,” Parsons Journal of Information Mapping (April 2010). http://piim.newschool.edu/journal/issues/2011/02/pdfs/ParsonsJournalForInformationMapping_Kalbach-James+Kahn-Paul.pdf

[7] IBM, “Capitalizing on Complexity,” (2010). http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/ceo/ceostudy2010/

[8] Booz & Co, “Executives Say They’re Pulled in Too Many Directions and That Their Company’s Capabilities Don’t Support Their Strategy,” (Feb 2011). http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/global/home/press/article/49007867

Thanks for this article, James – excellent article !

I am working with such alignment documents over the past couple of years. And I develop these documents most often together with a business analyst. But I call them interdependency models, – diagrams and or flows, because I often merge these things together with swim lanes.

In addition to features and functionality, I’ve also mapped things like business issues, goals and other information and business interdependencies.

I think a great way to communicate the relationship between user’s needs and business needs and to get and keep a holistic view on the project and various parts.

Let’s have more of the same! (btw. this is my 2nd approach to post a comment)

Great article, Jim. I have been asked in several companies to present new approaches to UX-and I always explain to them to take the mental landscape of the user into account, but never mapped them (I always wrote them out). I think though it is much more powerful visually. And it simple enough to do to potential convince upper management or challenging clients of the importance of it.