Would you rather take a photo using your phone, a point-and-shoot camera, or a digital SLR? How you answer this question is probably a good indicator of your photographic expertise. If you snap casual shots, your phone or a point-and-shoot camera will probably suffice. If you’re a professional photographer, on the other hand, you probably prefer using an SLR that gives you control over the focus, aperture, and exposure.

Expertise significantly impacts how we seek information online. Just as novice and expert photographers prefer different tools, so novices and experts behave differently when searching for information. Understanding these differences will help us design better search interfaces for both groups of users.

There are experts, and then there are experts

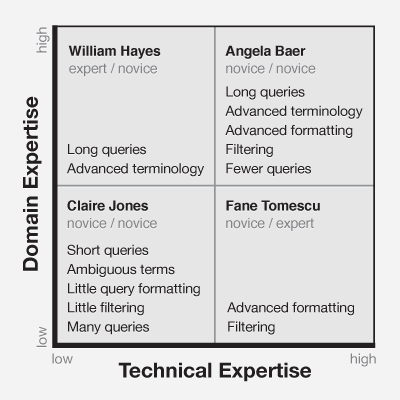

User expertise exists on two levels. If you’re an avid photographer, your domain expertise in photography will be quite high: that is, you’ll be familiar with the terms and techniques of the trade. Each of us is likely a domain expert in a few areas, and a complete novice in others. A second aspect is technical expertise. Familiarity with how computers, the internet, and search engines work significantly impacts how users seek information. Consider these personifications of each quadrant of expertise:

* *Angela Baer*, since completing her MFA at Pratt 5 years ago, is quickly building a reputation as one of New York’s up-and-coming fashion photographers. In the office connected to her studio, Angela edits her photographs on two large monitors and top-end computer. She delivers the edited shoots electronically to her clients, and regularly updates her online portfolio and blog. Angela is highly proficient using her computer, and when it comes to photography, she’s a domain expert.

* Though officially retiring over 10 years ago after a successful career in banking, *William Hayes* still sits on the board of a number of financial institutions. From his Elizabethan cottage on the Kent coast, he uses a 5-year old computer to exchange emails and access financial reports, though he prefers doing business on the phone and keeping up with the world though The Financial Times. While William is a domain expert when it comes to finance, his technical expertise is lacking.

* 18-year-old *Fane Tomescu* helps run an internet cafe in Braşov, Romania. Having saved for over a year, Fane recently came across a car that he’s considering purchasing. But when the time came to arrange car insurance, Fane had no clue how things worked. He asked his parents and friends for advice, and then spent several hours comparing providers online. Fane is a technical expert, but when it comes to insurance, he’s a domain novice.

* *Claire Jones* is a 9-year-old from Colorado Springs. Her school is holding a science fair and Claire has decided to build a model of the solar system using styrofoam balls suspended with string. Having left her science textbook in her locker over the weekend she was meant to start building the model, Claire used the internet to lookup information on the order, size, and appearance of each planet. Though she did eventually find what she was looking for (with her parents help), Claire would be considered both a technical and a domain novice.

While either dimension of expertise is valuable, users are most likely to succeed when both are present. There are, however, a number of design guidelines which can help both novices and experts succeed in their pursuit of knowledge.

Novices Orienteer

Image 2: An orienteer at the 2010 World Orienteering Championships in Trondheim, Norway. Photo by Torben Utzon.

Wayfinding is a challenge as old as humankind, but the discipline of orienteering originated in the Swedish military in the 1800s and is now a sport practiced throughout Scandinavia. Equipped with a map and compass, participants navigate between control points spread across many miles, making tradeoffs between distance and difficult terrain as they strive to complete the course in the shortest amount of time.

The strategies employed by novice users seeking information resemble the sport of orienteering. [1] Users with low levels of domain and technical expertise, typified by Claire Jones, share three main characteristics.

Short queries

Novices tend to enter queries that use about half as many words as experts.[2] Domain novices (like both Claire and Fane Tomescu), feel particularly unsure of which terms to use.

Many queries

Novices perform more queries than experts, but look at fewer documents. Although they frequently reformulate their query, technical novices often suffer from an anchoring bias [3] and make only small, inconsequential changes.

Going back

Novices are much more likely than experts to hit dead ends and seek to get back to a previous state.

These behaviours result in an orienteering-like strategy where novices “test the waters” with a short, general query, quickly skim the top results returned, and immediately reformulate the query based on their improved knowledge of the subject. [4]

Design considerations for Novices

There are a number of design considerations which can help novice users succeed at orienteering. In particular, novices need help formulating their query, refining their query, and backing out of trouble.

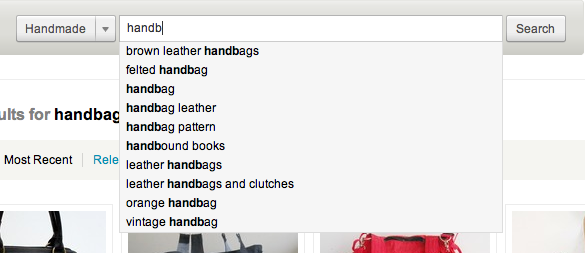

Autosuggest

As-you-type suggestions can help users get off on the right foot when they’re uncertain what to search for. Research has shown [3] that users are more capable of choosing a viable option from a list than they are of composing a question out of thin air. Autosuggest provides an opportunity to help users express specific terms (such as airports or stocks), and to suggest queries that other users have performed in the past.

Image 3: Autosuggest on Etsy.com

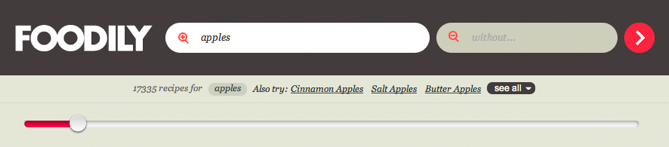

Related searches

After users have performed an initial search, they may still need help refining the query. A list of related searches can help the user break out of their anchoring bias and help them arrive at the optimal set of results.

Image 4: Foodily.com place related searches on the same line as breadcrumbs

Avoid zero results

If the user is presented with no search results, he may be disheartened enough to give up his quest. Avoid zero-result screens if possible. Tools such as automatic spelling corrections and query expansion (using synonyms and lemmatisation,[5] for instance) can help.

Image 5: Amazon.com’s handling of zero results

Breadcrumbs

Because novices tend to take wrong turns, they often need help navigating back to a previous state. Breadcrumbs are an ideal solution because they communicate both the user’s current location, as well as how to go back.

Image 6: Breadcrumbs on Zappos.com

Experts Teleport

Image 7: In Star Trek, crew members of the USS Enterprise stand on transporter platforms to be beamed down to a nearby planet.

While novices orienteer, experts teleport. Akin to being teleported to a precise but distant location, users with high domain and technical expertise like Angela Baer tend to jump directly to their final destination.

Longer queries

Experts enter longer, more specific queries than novices. Domain experts like William Hayes often rely on their vocabulary of specific terminology, while technical experts such as Fane Tomescu are more likely than novices to use formatting techniques such as quotation marks in their queries (87% of experts compared with 47% of novices according to a 2000 study [1]).

Fewer queries

Experts usually amend their queries less often than novices and move forward with a higher degree of confidence.

More Documents Examined

Experts tend to review more documents and follow a greater number of links within those documents. Domain experts are especially adept at quickly determining whether or not a given document is useful.

In essence, experts often construct queries using numerous highly specific words which act to teleport [6] them directly to a destination, cutting out the query reformulation often practiced by novices. After having arrived at a destination, experts are then likely to explore the surrounding territory.

Design considerations for Experts

Designing for experts involves facilitating their teleporting behaviour, helping them get to their destination as quickly as possible.

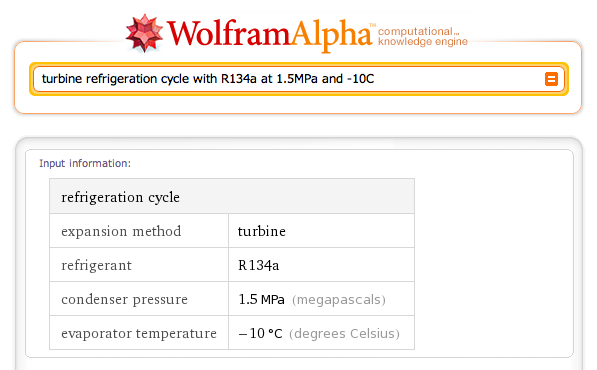

Advanced syntax

Technical experts like Fane are often willing to learn special commands in exchange for having greater control. Commonly supported operators include AND, OR, and quotes for searching for exact phrases.

Image 8: Wolfram Alpha is designed to understand domain-specific terminology and return computed answers.

Keyboard shortcuts

Keyboard shortcuts can also increase the speed of interaction. Google, for instance, allows users to press the up/down arrow keys on the keyboard to traverse results, and press return to go to the URL of the selected result.

Image 9: Google places a caret beside the currently-selected result.

Filtering & sorting

Experts are more likely to engage with advanced sort and filtering controls than novices, including operations such as selecting ranges, filtering by format, or excluding certain terms (e.g. everything that includes “apples” but does not mention “oranges”).

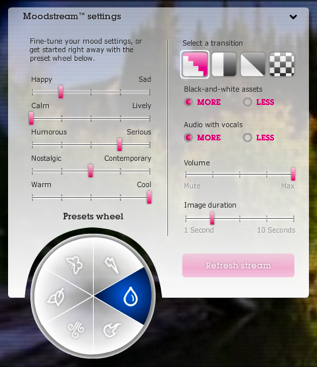

Image 10: Getty Image’s Moodstream lets users search for stock photos using sliders.

As-you-type results

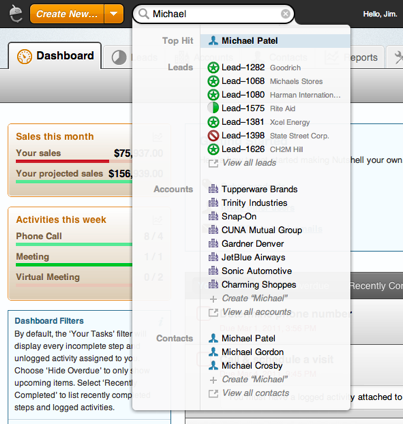

As-you-type completion interfaces most often display query suggestions to users. However, another use case is to present actual results in the autocompletion interface, enabling users to skip the search results screen altogether and go directly to a specific document.

Image 11: Rather than suggesting terms to search for, Nutshell returns search results directly without needing to go to a separate page.

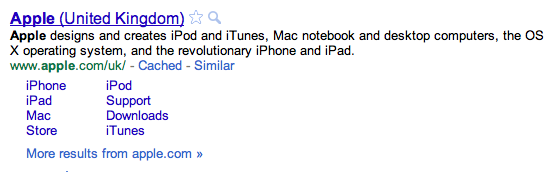

Result table of contents

Providing links to the top destinations within a result can reduce the number of steps required for the expert to reach his destination.

Image 12: Google sometimes provides links to the top-level pages within a given site.

Yin and Yang

While novices and experts practice two very different approaches to information seeking, it’s important not to overemphasis one at the expense of the other. As illustrated by the ancient Chinese symbol, understanding the behaviour of both novices and experts can help us design more informed, balanced search experiences.

The author would like to thank Cennydd Bowles for organising the UK writer’s retreat during which this article was written, as well as for the editorial guidance that he provided.

References

[1] Vicki L. O’Day and Robin Jeffries; “Orienteering in an Information Landscape”:http://www.hpl.hp.com/techreports/92/HPL-92-127.pdf

[2] Christoph Hölscher & Gerhard Strube; “Web Search Behavior of Internet Experts and Newbies”:http://www9.org/w9cdrom/81/81.html

[3] Marti A Hearst; “Search User Interfaces”:http://searchuserinterfaces.com/book/sui_ch3_models_of_information_seeking.html#section_3.5

[4] Morten Hertzum and Erik Frokjaer; “Browsing and Querying in Online Documentation”:http://www.cparity.com/projects/AcmClassification/samples/230570.pdf

[5] Christopher D. Manning, Prabhakar Raghavan and Hinrich Schütze, “Introduction to Information Retrieval”:http://www.cambridge.org/us/knowledge/location/?site_locale=en_US , Cambridge University Press. 2008.

[6] Jaime Teevan, Christine Alvarado, Mark S. Ackerman and David R. Karger; “The Perfect Search Engine is Not Enough”:http://people.csail.mit.edu/teevan/work/publications/papers/chi04.pdf

Hey Tyler

cool article, you know when you think something but can only manage to talk around it, you laid it all out so even I can digest it.

Do you have a list of site that get the balance spot on?

Just started reading the article is the Matrix graphic intended to show novice/novice in the upper right-hand, or expert-expert?

David,

Yes – it looks as if the matrix at the top is incorrect: Angela Baer should be expert-expert. Still the article was excellent.

As we’ve come up with numerous tactics for helping the novice and intermediate users (auto-complete, breadcrumbs, filtering) there seems to be little available for more expert users. I suppose that will come in time as database search times decrease and search algorithms improve. Wolfram|Alpha is a start but it still has a long way to go.

thanks for the timely article. differing levels of search proficiency is something that keeps coming up at work, but that’s difficult to frame. we’re also going to be investigating which KPIs / metrics / behaviors constitute a successful completed query. and, which indicate an ongoing progress or diminishing return for the user.