This article investigates content recommender systems. Because Netflix is probably the best known recommendation system and numerous articles have been published about their system, I will concentrate on their content recommendation mechanism as representative of the type. I will show that the Netflix mechanism contains characteristics of updated theories of emotion—mainly constructed emotions theory—but it still lacks several essential components. The lack of these components can explain some inaccuracies in Netflix recommendations and can suggest broader implications.

Continue readingCategory: Search and Metadata

Keep the Kitchen Cabinets from Overflowing

Don’t laugh. I’m sure you’ve done this before. At the office, there’s a refrigerator cleanup every two weeks. At least I think it happens every two weeks. The office administrator sends out an email or posts a note on the fridge, warning you that things will be dumped if they’re not labeled. You’ve seen these long-forgotten food containers of who-knows-when science experiments pushed up against the back of the fridge. Same with those things that start growing in your pantry….

Continue reading

Could You Hand Me the Dry Rub Please?

Tree testing is an effective technique for evaluating navigation and taxonomy. In an environment devoid of visual design and cues, tree tests are useful for assessing existing site navigation and proposed site structure changes. Using my kitchen, I devised a plan to test the findability of my kitchen’s spices and pantries.

Continue reading

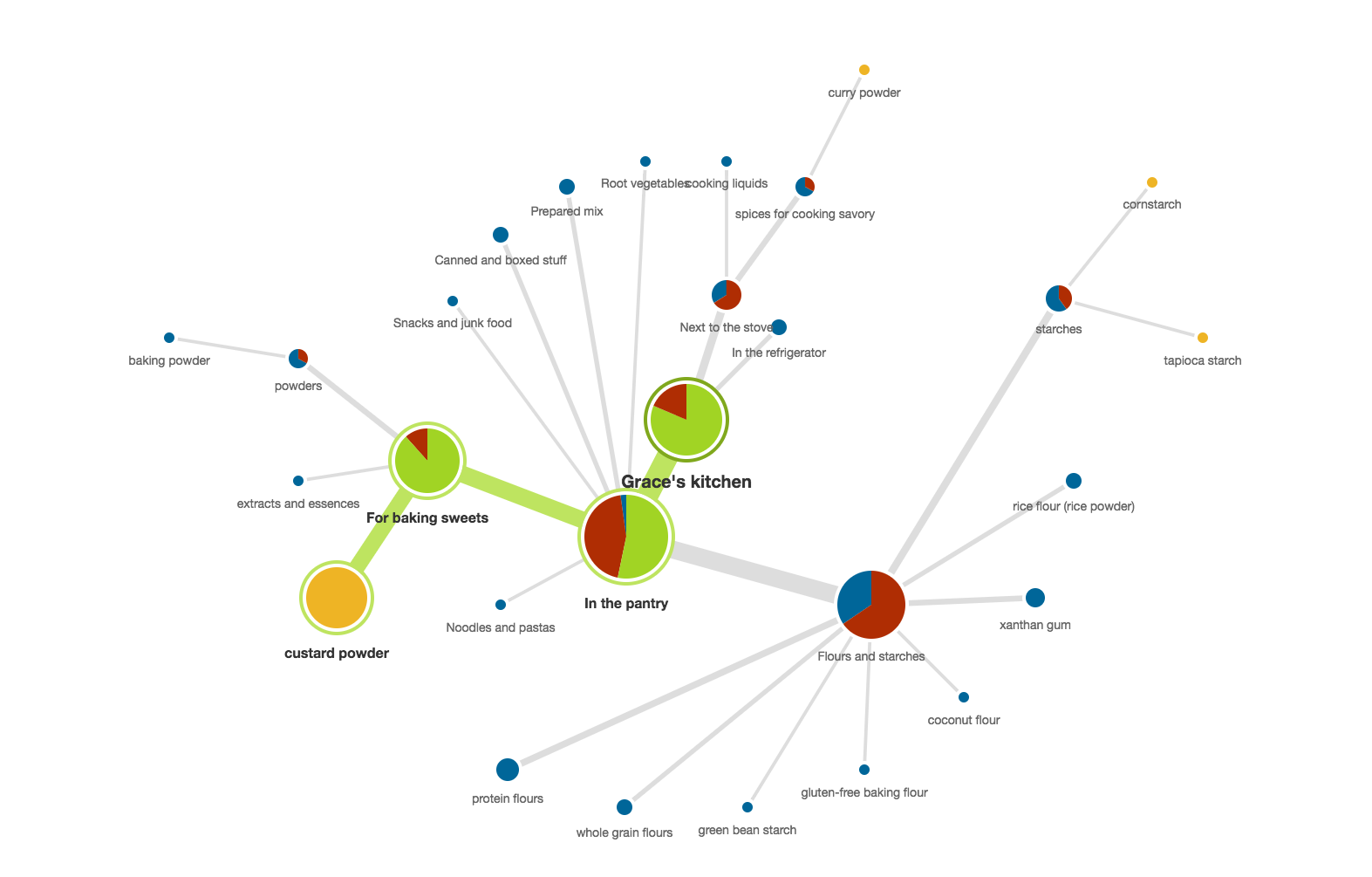

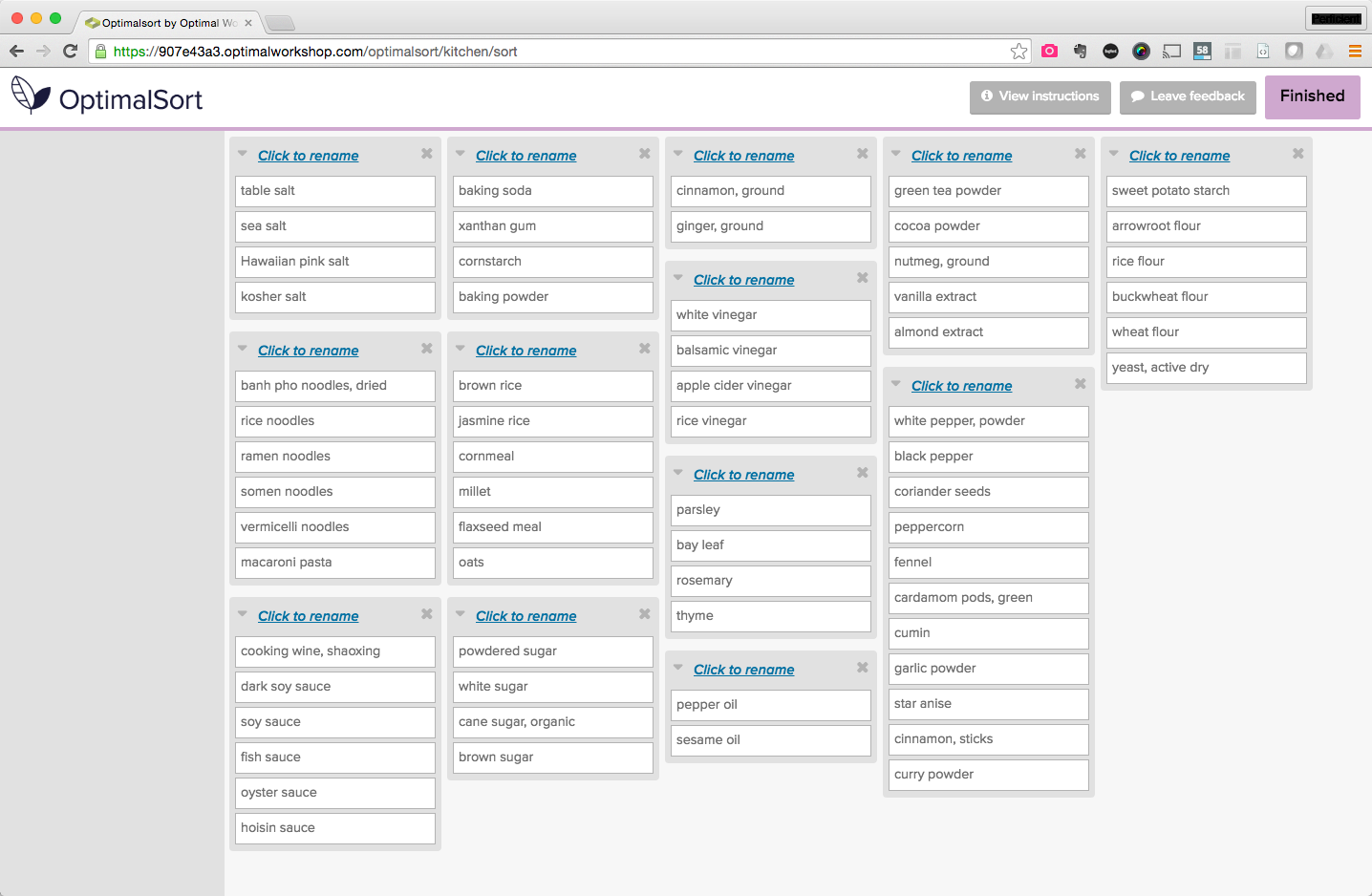

Card Sorting a Kitchen Taxonomy

Validating with users is a fundamental part of the taxonomy recipe because all this planning and re-organizing is in vain if my in-laws come back in six months and the kitchen reverts to its original state.

Continue readingWhat UX Designers Need to Know about Conversion Rate Optimization

Conversion is most often defined through sales, but it can also apply to clicks, sign-ups, repeat visitors, or any other metric that meets your organization’s goals. The real problem many organizations face regarding conversion, is that content is often still considered “the stuff that goes into the design.” Putting content at center stage means changing some of the fundamental ways we think about content in the design process and how it helps conversion. The principle of ‘form follows function’ states

Continue reading