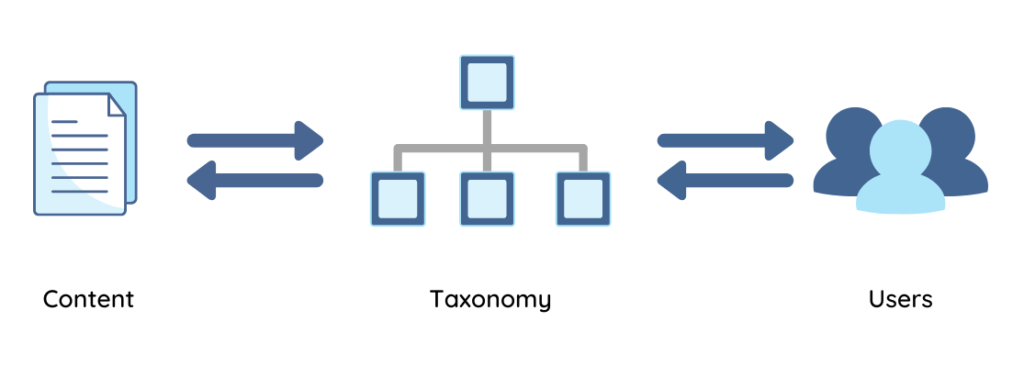

Taxonomies may be thought of as hierarchies of categories to group and organize information to be found when browsing, or as a structured set of terms used to tag content so that it can be retrieved efficiently and accurately. Sometimes the same taxonomy may serve both purposes, and sometimes two different taxonomies are used, one for each purpose, for the same content or site.

Taxonomies are not new, in fact there has been a lot written about them, including an informative series of six articles here in Boxes and Arrows by Grace Lau in 2015. An area that still needs to be better understood is exactly how taxonomies should be designed and implemented to be most effective.

Suiting Users Needs

The previous series of articles on taxonomy by Lau addresses many important points about taxonomies including building the business case for a taxonomy, planning a taxonomy, and taxonomy governance. In the first article of the series, “Planning a Taxonomy Project,” she states: “Understanding the users and their tasks and needs is a foundation for all things UX. Taxonomy building is not any different. …Who are the users? What are they trying to do? How do they currently tackle this problem? What works and what doesn’t? Watch, observe, and listen to their experience.”

In this article, I will explain the role of a taxonomy as a tool that connects users to content.

Understanding the users is of central importance, so let’s consider specifically two techniques we can use to make a taxonomy more suitable for its users: (1) adapting the names or labels of the taxonomy concepts (terms) to the language of the users, and (2) adapting the categorization hierarchy to the expectation of the users. The complexity is to do this for multiple different users with the same taxonomy for the same content.

Different Options for Concept Labels

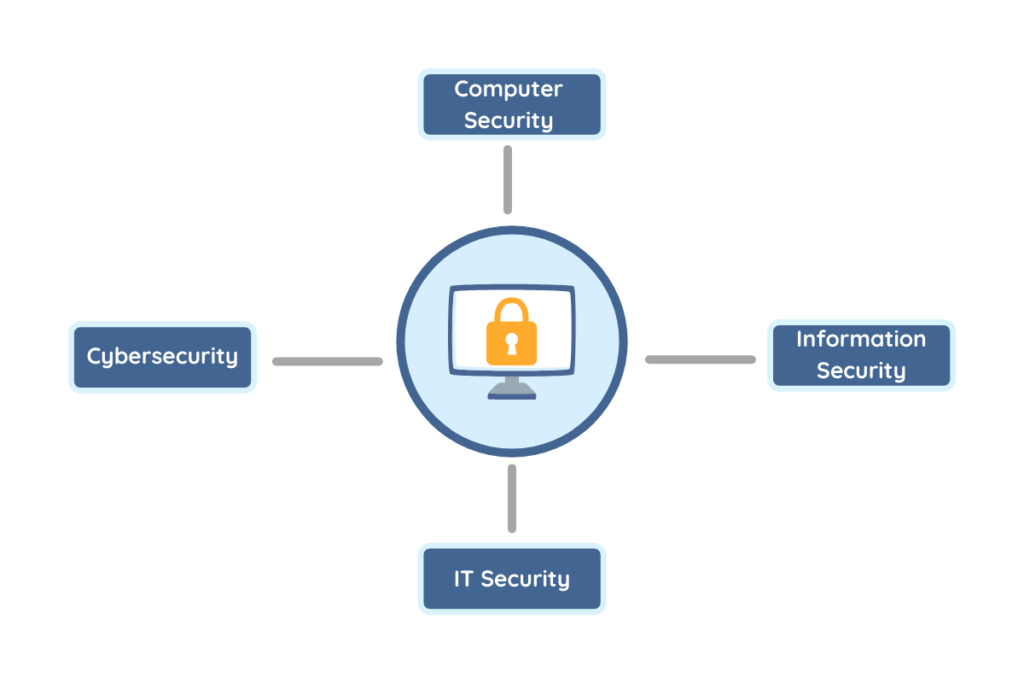

Different users will call the same thing by different names, whether it’s simple synonyms, such as Doctors vs. Physicians or Cars vs. Automobiles, or words or phrases that are not exact synonyms, but close enough,such as Computer security, Cybersecurity, Information security, IT security.

Taxonomies, in contrast to mere navigation labels, make use of such “alternative labels” for each concept, also known as non-preferred terms in thesauri. These are colloquially referred to as synonyms, but they are not exactly synonyms; they are labels for concepts that are sufficiently equivalent for the context of the content and the taxonomy. Thus, users searching on any various alternative labels will retrieve the same concept and it’s associated content.

It is a design choice whether the alternative labels are displayed before redirecting to the concept with the preferred label, or if the redirect is without a display and the user is taken directly to the tagged content set. Displaying alternative labels is educational for repeat visitors, whereas no display of alternative labels to end-users provides a clean, quick user experience. Users may not be aware that their chosen name was actually “alternative” and not “preferred.”

When a taxonomy is displayed for hierarchical browsing, only the preferred labels for each concept can be displayed. Designation of a preferred synonym as the label should reflect the wording preference of the majority of users.

If there are two distinct sets of users, such as employees and customers, where a number of preferred labels vary, it is possible to create two display versions of the taxonomy. This can be a little more complicated to implement because commercial taxonomy management software typically supports just one preferred (i.e. display) label per concept by default. You may need to create two separate taxonomies and link them at equivalent concepts.

Different Options for Categorization

Different users may categorize differently and will look for the same thing in different places. Lau’s articles gave the example of different users of a kitchen wanting to group different ingredients differently. This would certainly be a challenge in sharing the same physical space.

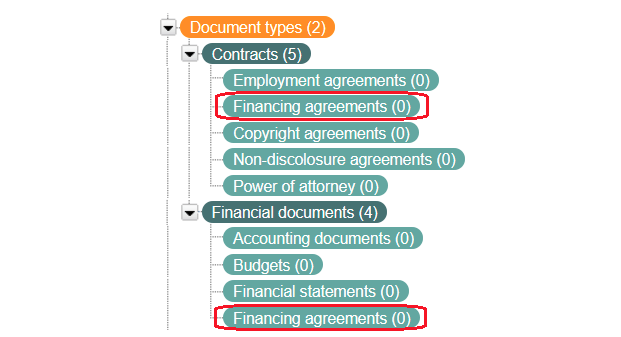

Fortunately, taxonomies are used to describe digital space so there is flexibility. While a physical object can exist in only one place in a kitchen, a library shelf, or a store shelf, the same taxonomy concept representing an idea may exist in more than one place in a taxonomy hierarchy.

In another example, some people might categorize Financing agreements under Financial documents and some might put the category under Contracts.Thus, we can have the taxonomy concepts of Financing agreements appear as both a narrower concepts of Financial documents and as a narrower concept of Contracts, and all the same tagged documents will be found in both locations. This is what taxonomists call “polyhierarchy.”

One thing to keep in mind is that polyhierarchy is appropriate for hierarchical taxonomies, not for faceted taxonomies of attributes or filters (such as ecommerce facets of Size, Color, Material, and Style), where the same concept should exist in only one facet.

Methods of Obtaining User Input

The methods to develop a taxonomy involving users have some similarities and some differences compared to other UX methods. Card sorting can be used to gather user input for taxonomies, but it is effective only for 2-3 levels of a hierarchical taxonomy and is not as effective for designing facets, where the challenge is to identify ways to describe not ways to categorize. Some hierarchical taxonomies have many more levels, so card sorting is most practical for just the top levels, or else it would become too time-consuming for the multiple hierarchies at each level.Taxonomies are more extensive than just the navigation structure of a website.

Users of a taxonomy include both those who are looking for information and those who would be using the taxonomy to tag content. Representatives of these two different user groups should be interviewed with different questions. For example, those who need to retrieve content may be asked questions around the challenges in finding content and search terms; those who tag content may be asked questions about challenges in finding appropriate terms for tagging. Similarly, user testing of the draft taxonomy should also involve both uses of tagging and uses of retrieval.

Content management users, especially those dealing with particular subject domains, may be asked to submit lists of suggested terms that fall into deeper levels of the taxonomy. Those submitting suggested terms should be provided with clear guidelines, that the terms are for tagging content, so that they do not suggest terms that are too specific and not reflected in the actual content. These terms then should be reviewed and discussed with the taxonomist to make sure that they are suitable for the taxonomy.

Another method to gather user input indirectly for a taxonomy is to analyze search logs to identify what words and phrases users have been entering into a search box to find content. These words and phrases should be considered for alternative labels (synonyms) for taxonomy concepts, and possibly for additional concepts in the taxonomy, if warranted by the content.

Conclusions

While UX research is a formal job role, taxonomy research is not, although there are standard practices. Taxonomy research is rolled into the overall taxonomy design and creation job. Because taxonomies are based on the content they are tagged to, taxonomy creators may fall into the trap of exclusively focusing on making the taxonomy reflect the content without also considering the need of making the taxonomy suitable for its users. Taxonomy user research may not be as formal or extensive as other UX research, but it is critical to the success of a taxonomy.

Heather Hedden will be conducting a workshop on this topic at the 2021 Information Architecture Conference. Participants will learn taxonomy creation principles and how to address the issues of designing a taxonomy to serve users.

Featured photo by KOBU Agency on Unsplash.

Additional images by Linda Ramirez and Heather Hedden.