Most website designers are aware that an important part of understanding the background of any website redesign project is performing a content inventory as well as a content analysis.

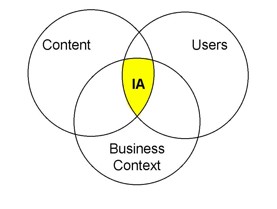

After all, authorities Lou Rosenfeld and Peter Morville include this famous Venn diagram in their classic Information Architecture for the World Wide Web:

Clearly, we are supposed to understand the current website content before we begin the process of redefining and reorganizing the website.

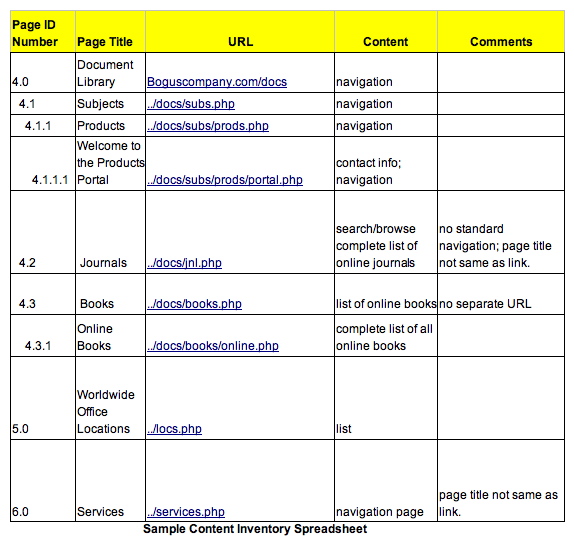

So we all dutifully go through the website and prepare a content inventory spreadsheet capturing page titles, details of page content, and so on.

Each content inventory contains a different set of columns and fields; each has a purpose specific to the needs of the particular site being analyzed. Sarah Rice has developed another example(xls) that’s available as part of the IAInstitute’s tools project.

Sarah’s version captures additional information from the site, uses an indented format for capturing the page titles at different hierarchical levels and uses color coding to indicate content types, external links and open questions.

So doing a content inventory is all well and good, but what exactly is it about the content that we are supposed to understand? What are we supposed to tell our client, other than that the website has 4,321 pages, of which 358 are dead-ends, 427 have no page titles, 27 have content that has expired, there are 432 different document templates in use, and there are 17 distinct document types?

In her 2002 article on rearchitecting the PeopleSoft website1, Chiara Fox noted that document inventories and analyses form part of bottom-up IA. “It deals with the individual documents and files that make up the site, or in the case of a portal, the individual sub-sites. Bottom-up methods look for the relationships between the different pieces of content, and uses metadata to describe the attributes found. They allow multiple paths to the content to be built.”

Certainly content relationships are important, as is the development of appropriate metadata to describe content, but are there specific things we can look for during a content inventory? In the remainder of this article, I hope to show that the answer is a resounding “Yes.”

Content Analysis Heuristics

In the fall of 2006, I was working on a navigation taxonomy project for a major media industry client that was redesigning its public-facing website. It was while preparing the content analysis report for that client that I developed the following set of 11 heuristics for analyzing website content.

- Collocation

- Differentiation

- Completeness

- Information scent

- Bounded horizons

- Accessibility

- Multiple access paths

- Appropriate structure

- Consistency

- Audience-relevance

- Currency

These heuristics provide an important way to organize my report and help me identify significant problems that I might not otherwise notice. They provide qualitative results and indicate general trends, but are not statistically valid in the strict sense.

While you can use heuristics for any kind of website or intranet, regardless of size or content, certain heuristics may be less applicable for some sites. For example, a game site that is designed to encourage users’ exploration may not present bounded horizons. In fact, it would be doing gamers a disservice to let them know the entire game path from the start. So some evaluation is necessary as to whether or not (or how strongly) a specific heuristic should apply to the site you are designing.

Each of these heuristics will be discussed in detail in turn.

Collocation

Bring together items with similar content or items about the same topic in one area.

Users should be able to find all relevant content easily. Accordingly, collect related content in one area, or at the least, make it accessible through one area. While the exact way content is related may differ (e.g., by document type, by subject, by author, by date), the information that users will want to find in one place should be in one place.

Obviously, if the quantity of content is large enough, users may have to visit different subsections to view all of the related content. In that case, the content organization itself should make it easy for users to understand how different areas are related and how. When those areas are viewed together, they will provide a unified picture of the product or subject of interest.

The important point here is to not have “dangling” content that lives in one area perhaps because of historical growth of the website, while most of the related content is accessible in another area.

Differentiation

Place dissimilar items or items about different subject areas in different content areas. Use navigation labels for different areas that clearly indicate those differences.

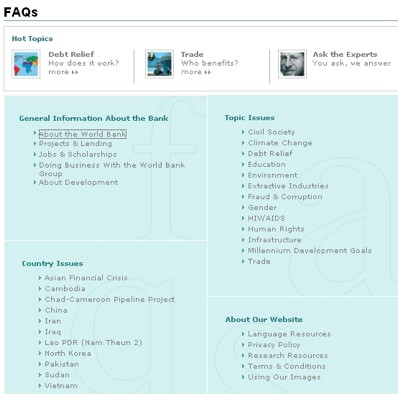

One of the typical ways that websites break this guideline is in the use of Frequently Asked Questions. FAQs often bring together a wide variety of topics on issues that are important for users. Perhaps website creators think they are making it easier for users to find information when they put everything “important” in one place.

The problem for the user is that their search for specific information becomes like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Unless FAQs use a well-thought-out topical arrangement, users may have to read through every question in a long list to find the particular information they are looking for. How much better it would be to separate this content into meaningful sections!

The World Bank’s website is one example of an organized set of FAQs. They use four main topics and clearly identify secondary subject areas for each. Yet even this example is not totally successful in using a good topical arrangement, as the “Ask the Expert” section contains the usual miscellany of important information without topic differentiation.

“World Bank Website: FAQ Section, February 2007”

Completeness

All content mentioned or linked to should exist.

In this day and age, there is no excuse for the 404 Error, Page Not Found. Nor is there any excuse for the “Under Construction” sign on a page. If the content doesn’t exist, don’t lead the user to where it might be sometime in the future.

If you mention a related topical area, be sure that content is actually on the website. Directing users to non-existent information simply breaks their trust in the website.

Information Scent

Content labels should be appropriately descriptive of content so that users know they are on the proper path to finding the information they are looking for. Content labels should therefore also reflect information collocation and differentiation.

The idea of information scent was first developed by Peter Pirolli, Stuart K. Card, and Mija M. Van Der Wege of the famous Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). In their paper [2], they note that, “Information scent is provided by the proximal cues perceived by the user that indicate the value, cost of access, and location of distal information content. In the context of foraging for information on the World Wide Web, for example, information scent is often provided by the snippets of text and graphics that surround links to other pages. The proximal cues provided by these snippets give indications of the value, cost, and location of the distal content on the linked page.”

Simply put, a good website will provide users with strong clues as to the content that can be found by clicking on a specific link.

In his Alertbox column of June 30, 2003, Jakob Nielsen says, “ensure that links and category descriptions explicitly describe what users will find at the destination. Faced with several navigation options, it’s best if users can clearly identify the trail to the prey and see that other trails are devoid of anything edible.

“Don’t use made-up words or your own slogans as navigation options, since they don’t have the scent of the sought-after item. Plain language also works best for search engine visibility: searching provides a literal match between the words in the user’s mind and the words on your site.”

BOUNDED HORIZONS

A site’s users should be able to easily understand the breadth of content they are looking at.

While a labyrinthine website that leads users along a single, linear path through groves of rambling information might be appropriate for a conceptual artist’s site, such a principle for organizing content is useless in most cases.

Users should be able to identify in relatively short order the depth and breadth of relevant content.

Providing good navigation cues and a strong hierarchical structure when appropriate means that users quickly learn how long their search for information may take. They can thus make an informed decision whether to continue content exploration on your site or to abandon ship and continue elsewhere.

Accessibility

Users should be able to access the content they want through the browsing hierarchy or by using search.

It may seem obvious, but I have seen sites where search is so poor and navigation hierarchy so limited that it is hit-or-miss whether users can find what they seek. Often, information is hidden by contextual links to content areas not exposed in the main navigation. You are no doubt devoting considerable time and effort to creating content. Let users find it.

Multiple Access Paths

Because users think about content in different ways, they should be able to take multiple paths to get to specific content.

Facets provide one of the important ways to provide multiple paths to content. I’m looking for a blue coat to go with my gray suit. Or I want a wool sweater, because my cotton one won’t cut it in Boulder, Colorado. My wife says it has to be Prada. Size, color, material, designer: each can be the most important way for someone to find an item or some content.

While faceted navigation schemes are often useful for e-commerce sites, they can also be especially useful for information-rich sites. You might provide search filters by document type, date, or author in addition to subject. For scientists, methodology or researcher often become more important than subject in finding relevant research papers.

Multiple access paths provide greater findability for more users.

Appropriate Structure

Organization of content should (1) match users’ mental models of the information space and (2) support the differences in users’ information-seeking behaviors: known-item finding; exploratory browsing; unknown information finding; and refinding.

Whether you have multiple access paths or a single hierarchy, the organization and structure of your site should be appropriate to both the nature of the content and to your users.

As with many of these heuristics, there is no single “best” approach. Rather, based on your knowledge of business context, users, and content, determine whether content access structures are valid for the specific context.

Consistency

Whenever possible, content structures in similar content areas should be consistent.

If all of your products have accessories, they should be accessible through similar links or tabs or icons. Consistency enables users to more quickly build a mental model of your site and to understand how to find information.

Think of the rather complex page structure on Amazon.com for a book:

- Cover illustration

- Title

- Author

- List price

- Savings

- Availability

- Delivery information

- New/used copies

- Customers also bought

- Editorial reviews

- Product details

- What customers ultimately buy

- Help others find this book

- Customer tags

- Customer reviews

- Customer discussion

- Listmania

- Recently viewed items

- Similar items by category

- Similar items by subject

Who in their right mind would create such a structure? Obviously people who did lots of research on their users. Why does this structure work? Because once we have seen it, we know that we will see it again and again and again. Power users of Amazon.com probably know exactly how many turns of their mouse’s scroll wheel it takes to the to the information they want.

This book product page may be long and complex, but it is consistent in structure and format. We know what to expect. A good website provides users with a consistent experience.

Audience-Relevance

Content organization allows different audience segments to easily find relevant content.

This heuristic is especially important if your site’s audience comprises multiple distinct segments, holiday travelers and business travelers, or students and faculty. In some cases, it might be appropriate to use audience segment as the primary way to organize information.

Additionally, audience relevance may be legally mandated. Drug websites, for instance, are governed by FDA regulations dictating that prescribing information should be available only to health-care professionals, not the general public.

However, even with a relatively unitary audience, you want to be sure that the site’s labeling system is appropriate for its users. It is also important that the site mirror how users think about the site’s content.

Currency

Content should be kept up to date.

Nothing frustrates a user more than finding that the information you provide is out of date: you don’t make that product any more, that color is out of stock, or that drug is no longer indicated for that condition.

Put an expiration date on all content through your CMS, thus ensuring that it is reviewed for currency on a regular basis. That is a good way to ensure that you website provides users with information that is still valid.

Another way to ensure currency is to have a good website maintenance plan in place. Such a plan should cover, among other things: who is responsible for content reviews, extraordinary internal and external events that should automatically trigger a content review, and how users or content authors can suggest a review.

Conclusion

Although the above eleven heuristics provide good qualitative information, you may find it helpful to add a five-point scale (derived from the Lickert Scale), indicating how well the site under analysis conforms to the heuristic:

1. Strongly deviates from the heuristic

2. Deviates from the heuristic

3. Neither deviates nor conforms to the heuristic

4. Conforms to the heuristic

5. Strongly conforms to the heuristic

Providing such a scale may help the client understand the results of your content analysis better than a purely descriptive report.

Whether you use a numerical scale in discussing the results or not, provide your client with a written content analysis heuristics report. You can offer the analysis as part of your content inventory or content analysis report, or you can create a separate document entirely. The report should include sections describing your evaluation of the website using each of the heuristics (if applicable). In discussing each heuristic, indicate how well the site meets the heuristic in general and then note instances for improvement, or places where the site does not conform to the heuristic at all.

The following are several sections from an actual content analysis report that used these heuristics (modified to mask the company’s identity).

Although [company].com is relatively good at gathering like content into one area, there a number of exceptions. For example, information on money and vacations is available as a content sub-area under both the Money and the Vacations topical areas. However, the content is different in each place. In essence, there are two separate areas dealing with the same subject of money and vacations.

The most significant problem area with regards to collocation is the Specials section, which offers much content that would be best distributed among and combined with other areas of the site.

…

The [company].com Specials section is the primary place where the principle of differentiation is not observed. It combines subject areas such as health, relationships and travel, along with a number of the company’s special projects. Because this content area contains such disparate information, users may not always spend enough time looking through it to find relevant information.

…

Because labels on the website often reflect a supportive and encouraging emotive vocabulary, those labels sometimes obscure important information. For example, it is doubtful that a user looking at “Tips for Living” would realize that there is information on home decoration and time management in that section.

…

[Company].com generally supports exploratory browsing and unknown information finding. However, shortcomings in the search results (a limit of only 21 results) sometimes make it difficult for users to find specific information.

…

[Company].com is not always good at providing access to audience-relevant information. For example teachers may be totally unaware of the fact that there are classroom videos and teaching aids available in the Library section.

By arming the client with such information, you give them more well-structured ideas about how to improve their website. And that, after all, is the goal of our work.

Endnotes

[1] Fox, Chiara, “Re-architecting PeopleSoft.com from the bottom-up”:http://www.boxesandarrows.com/view/re_architecting_peoplesoft_com_from_the_bottom_up in Boxesandarrows.com, June 16, 2002.

[2] Pirolli, Peter, Stuart K. Card and Mija M. Van Der Wege, “The Effect of Information Scent on Searching Information Visualizations of Large Tree Structures”:http://www.inxight.com/pdfs/info_scent.pdf.

[3] Nielsen, Jakob, “Information Foraging: Why Google Makes People Leave Your Site Faster”:http://www.useit.com/alertbox/20030630.html.

Thanks Fred. Your article does a nice job of discussing qualitative Content Auditing. Can I confirm that you would do both heuristic (qualitative) and the quantitative auditing mentioned at the start of the article? As I feel that both obviously provide very different types information both of which are very important, what is your take on this?

When auditing I would suggest preparing your approach, data capture templates and methods well in advance to assist the speed and coverage of the audit. A simple test of your audit templates can be done – Ask yourself what are trying to achieve with the audit, i.e. what questions are trying to answer – Fill in your template with dummy data – See if you can answer your questions set in step 1.

I like to run the heuristic audit in a way follows a natural browsing pace as far as possible, stopping to notate every couple of minutes or at the end of natural paths (feel the user experience).

The quantitiative content audit is very useful for working out content migration plans or content focusing as part of on going or new developments.

Having started on a long term auditing plan I also ran a couple of additional exercises to get a complete view of the site, when applicable auditing the content administration tools side – often an area of low quality user experience, caused by a lack of focus on the system that will provide the actual engine to the site.

I think the heuristic term of Accessibility that you use may be better termed as Findability, courtesy of Peter Morville, as Accessibility infers that you may have been evaluating the sites Accessibility compliance, which from your discussion definately appears to be more in keeping with Findability.

Thanks for the article.

Richard Marsh

http://www.creative-resonance.com

Richard, thanks for your comments. You are right that I also do quantitative auditing in addition to the heuristic evaluation discussed here. Your suggestion that “accessibility” might be better termed “findability” is a good one. I was using “accessible” in its more traditional meaning.

Hi Fred. It is an excellent article. I have a query. While you have include a quanitative aspect to a rather qualitative analyis,it would still perceived to be subjective by sceptics. In your opinion, based on your experience, how many experts should be performing this analysis to reduce the subjective element?

Fantastic article!

Fred, thankyou for the interesting article, it certainly made me think about using heuristics where I work.

The company I work for has dealt with clients who are very paranoid that we are ripping them off, or trying to “upsell” things that people don’t need (would you like fries with that?). It is quite possible that we could say, for Appropriate Structure, “This strongly deviates from the heuristic, so you need to totally restructure the site”. They are likely to think “why”, and we would have to explain to them the reason why their site does not have the right structure for their content and intended audience. Quite a few of our clients are non-technical people, and even after explaining all the factors involved, as one customer recently put it after my boss diligently explained the items that would be invoiced, “This is bull****!! I don’t understand a word f-ing word of this! How do I know you are not just making it up!”

I find people understand things like “Your site is getting 20% more hits this month, you are ranked number 3 on google”, but try to explain anything more subtle and their faces turn blank, and they mutter something about just wanting a website, “I’m paying you to work that out”. Ultimately if we DO work it out for them and they don’t like it, we have to do it all again. So any tool that can reduce this likelihood would be a godsend.

I think the ideas presented here are great, anyone with an ounce of common sense can see that the points you mentioned are essential factors in the process of analysis and development, and there will always be people skeptical of anything that smells of subjectivity. I personally believe there is a lot of validity in a qualatitive study which should be used to complement quantative results. Communicating such results to the client is another issue entirely, and one which I am still trying to work out.

Thankyou Fred.

Sorry for my rambling post… First day here.

Mark and Alexander,

Thanks for your kind words.

I’m glad you can see the value in how the heuristics will help you when discussing your work with clients. Anything that we can do to increase client’s understanding of our work is always important.

I can say that it was precisely in trying to define what the difficulties with a client’s content were that led me to the development of the heuristics.

Rajesh,

I realized that in the rush of preparation for the IA Summit, I never answered your query. I don’t that that increasing the number of people working on content analysis will increase the perception of its objectivity. Rather, what is important is providing concrete examples to the client. Just saying, “Your site doesn’t meet the heuristic of collocation.” isn’t enough. Rather we have to point out the five different places where information on the same subject is spread and then point out that because there are not links among the sections that users will most likely not be able to find all of the information that is relevant to them.

Certainly one must be careful of bias or preconceived notions in any work that we do, so having someone else to validate or verify our results can also be helpful.

Thanks, Fred, for the exhaustive article. Having not done any content analysis before, this is an excellent primer on the subject. I wasn’t sure how useful an analysis could really be but after reading this it makes total sense.

How would a quantitative evaluation differ? Would I be correct in assuming its more of a hard statistical expression of the content?

Thanks

Tom

Tom,

Thanks for your kind remarks about the article. Glad it is of help to you.

A quantitative analysis/evaluation really focuses on specific numbers: How many different page templates are currently used? How many document types do we have and what are they? What is our most-used content? How current is content? How many content authors do we have, etc? Essentially items that can be directly measured or counted.

Obviously there is a place for quantitative analysis also, in addition to the types of qualitative analyses I discuss here.

Fred

This is an excellent analytical tool-set which I’m sure can offer a basis for many different kinds of content analysis. My own qualitative analysis for large-scale sites departs more from user scenario’s (we do lots of interviews) and the goals of the site, but all of these aspects play a key role at one point or another. Thanks very much! This will greatly help me explain content analysis to my students at the Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences.