“Whether you’re designing tax forms, toasters, or retirement accounts, taking time to describe who your users are and what they need can always be helpful for creating a product that will best serve them.”

You’ve tried it all. User personas as posters, ala Alan Cooper, hanging on the office walls. User personas as cardboard cutouts, sitting at the conference table with you and your client. User personas as glossy deliverables. As paper mâché projects. As collages, comics, mood boards, Word documents, lists, charts, and just regular conversations.

Through all your attempts to bring user personas into your project, one thing remains consistent: user personas are hard to get right. And even if you get them right, they’re even more difficult to integrate into your day-to-day process.

Steve Mulder, user persona aficionado, has some suggestions. A whole book of them, in fact. That’s why Boxes and Arrows needed to interview him after getting a preview of his new book, The User is Always Right, late last year. Steve’s been kind enough to talk with us and to provide us with a free sample chapter below.

Liz Danzico: Congratulations on your book. What is The User Is Always Right, and, well, is it true?

Steve Mulder: This book was born out of the sinking feeling that, despite all the constant preaching about knowing your users, too many websites are created and grown without keeping users in mind. More companies are doing user research than ever before, but they’re challenged with making the results of that research understandable and actionable. Enter personas, which are generating more and more buzz.

But what are the various approaches to creating personas? How do I actually interview and survey users? How do I segment users and turn the segments into realistic personas? How do I use personas for directing overall business strategy, scoping features and content, and guiding information architecture, content, and design? The intent of this book is to give practical advice and direction on creating and using personas, and also to challenge all of us to bring personas to the next level.

So, is the user always right?

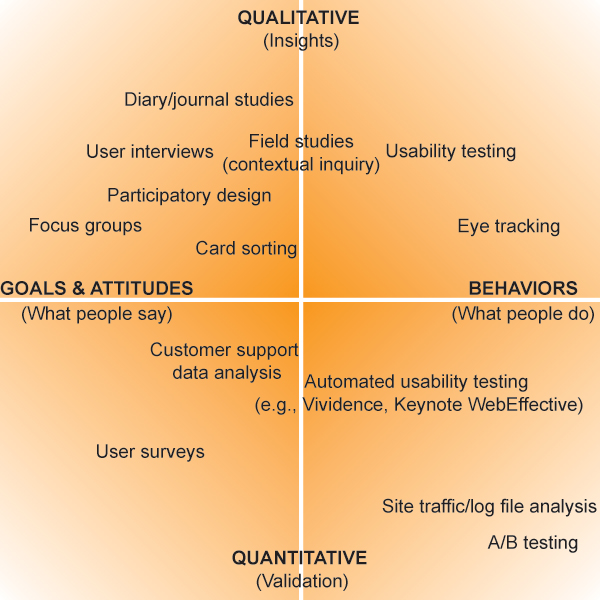

Yes, philosophically. Successful companies recognize that putting users at the center of decision-making is almost always a good idea. But taken literally, the book’s title is also a lovely, overstated attention-grabber. Let’s face it, users often can’t tell you the right direction for the website. But buried in their goals, behaviors, and attitudes (both stated and unstated) is everything you need to discover the right path. That’s why good user research isn’t just about listening to what users say.

So it sounds like analyzing research—not just plain listening to what users say—takes a certain kind of background and training. Is that true, or can anyone conduct this kind of research?

Sure, anyone can conduct this kind of research provided you don’t care whether the output is useful or not. Okay, maybe that’s harsh.

As our work as information architects, designers, marketers, or insert-your-favorite-title-here gets more sophisticated, so, too, do our methodologies. Talking to a dozen users and making critical business decisions based solely on that qualitative research just doesn’t cut it within some organizations. Increasingly, we need to raise the bar and invoke proven tools from other disciplines, such as statistical analysis techniques that enable us to generate persona segmentation based on quantitative research. We need to incorporate data on not only what users say (in a survey, for example) but also what they do (log files and search logs). All of this can inform the creation of personas that represent a much more accurate and useful portrait of users.

Raising the bar means bringing in specialists more often, or training ourselves in new specialties. But honestly, isn’t that what we love most: pushing ourselves in new directions?

Indeed. But, as you say in the book, “pushing ourselves” means playing nicely with others in the company—others in departments that may not cooperate or throw up roadblocks. You point out, “Increasingly, companies are realizing that their Web sites need to be a cornerstone of their marketing, sales, and servicing efforts.” Can we leverage these departments with their new outlook on research for tools and techniques?

Absolutely, though I’d describe it as “collaborating” with them rather than “leveraging” them. Running a business based on actionable knowledge about users requires understanding those users throughout their complete lifecycle with an organization. Thus, all customer touchpoints within a company (from sales and marketing to user experience to customer service) must come together to create a shared vision of who the users are and how to best serve them. Personas that are more rigorous and that are communicated in the language of business are more likely to bring these different groups together and bring their strengths to the table.

I’d love to talk more about the rigor or fidelity of personas. In the book, you go into great detail on how to show the right personal information in personas. Can you describe the process of turning your research into a reality?

As you saw in the book, I believe that personas are only as good as they are actionable, and that means creating realistic details that will actually inform decision making. If I say that Francis the First-Time Home Buyer loves Billy Idol, that’s an interesting detail that makes her persona more realistic, but it doesn’t help me make critical decisions about the real estate site I’m working on. On the other hand, if I say Francis is embarrassed by her ignorance of real estate and unlikely to ask friends for advice, that’s helpful information for deciding what content the site could offer and how that content should be provided.

With personas, the right kinds of details matter, and they typically involve goals, behaviors, and attitudes.

When you’re unable to talk to real people to gather research (and you give us your blessing in your book to do so!), where do you look for inspiration for creating them?

Let me first say that talking with real people is always better than not doing so. I don’t believe it’s ever a waste of time to do primary research with users. And it doesn’t take much time or effort to set up a few one-on-one interviews with typical users.

However, when even that kind of limited research is impossible, personas based on no research are better than no personas at all. At a minimum, personas force everyone to agree on and apply a shared vision of who you’re targeting and what they need, and that’s a very good thing. When creating personas in this way, involve colleagues in your organization who have direct contact with customers, such as those in sales or customer service. Take advantage of internal knowledge that already exists, then look externally at research by companies such as Forrester Research. These can be great sources of insight for brainstorming which goals, behaviors, and attitudes might be most effective for defining your personas.

I was surprised to see that you recommend using very specific photos to represent the personas. Isn’t a more general photo better? Isn’t that what Scott McCloud taught us?

Ahh, but remember that in Understanding Comics, McCloud points out that generalized sketches work well in comics because they better enable us to see ourselves in the comic. With personas, however, the whole point is to see real people as our users and not focus on ourselves. Choosing very specific photos forces us outside of the habit of thinking about ourselves. Suddenly there’s a very real person staring back at us with specific goals, behaviors, and attitudes that we must address.

Some of the examples in your book are spectacular in that they reveal details of deliverables that are often hidden behind proprietary walls. Of particular interest was the way you wove personas into the process of prioritizing features. Did extreme programming have any influence on this tool? Bringing “user stories” into their feature prioritization is a standard part of that process.

Actually, no. The tools I show in the book were simply a natural extension of what many of us already do. We talk about things like scenario-based design and use cases, but we seldom make the connections explicitly between the user research we do and the decision-making tools we use. At Molecular, we spend a lot of time drawing these connections, so it’s clear to our clients that decisions we make about features, IA, content, and design are all tied back to our knowledge about the real people we serve. Making personas a living part of the entire process is at least as important as creating effective personas to begin with, so we embed personas in our deliverables as much as we can.

Can you talk about a time where you weren’t able to make personas part of the process despite your best efforts? Perhaps there are even times when integrating personas is not useful.

I remember a time when my team presented personas to a client using cardboard cutouts and a little role-playing, only to find that this company’s culture frowned on anything remotely touchy-feely. They wanted hard data, and we foolishly didn’t take the time to understand our audience before presenting personas to them. On that project, we continued to use personas, but because our initial presentation left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth, the personas simply weren’t as effective in guiding decision making. As you can imagine, we didn’t repeat that mistake.

I was excited to see you start a book site to supplement and support the book. What are your plans for the site going forward?

The blog is intended to continue the conversation. A book is a snapshot frozen in time, but of course personas continue to evolve as a useful tool for managing websites. So my site tracks the latest news and opinions about personas, and I hope it becomes a useful resource for the community.

Did you use personas to create and guide the content for your book? How applicable are these techniques for other media?

Yes, I sketched out a few personas for the book, and found them very helpful for guiding not only what I wanted to cover, but also how to approach each topic. One persona was very much based on a client that I worked closely with, but I’ll never reveal that person’s true identity!

I absolutely believe that personas are valuable across many different domains. Whether you’re designing tax forms, toasters, or retirement accounts, taking time to describe who your users are and what they need can always be helpful for creating a product that will best serve them.

What’s next? Are you excited about using real stories and people to guide design? Are there changes coming in the way we use personas in the process?

More and more, businesses are letting real users have a tangible impact on decision-making, and I find the results exciting. My favorite current example is the way Starwood Hotels has used Second Life, that crazy virtual environment everyone is talking about, to create a large, detailed 3D model of a new chain of hotels it’s creating. In this virtual environment, users can walk through the hotel and give feedback on everything from the overall architecture to the fabrics. Starwood gains valuable feedback for improving its product before actual construction begins, and users get to contribute in a very real way.

The whole point of personas is to make users an active part of the process of running your business. Virtual or not, personas keep our eyes focused on the people who matter most: the customers we serve and who send us the business results that we so richly deserve.

![]() Download Chapter 3, The User Is Always Right (PDF)

Download Chapter 3, The User Is Always Right (PDF)

Liz, the link to his book site and Chapter 3 were a great bonus to a good article. What I like about Mulder is that he is from the camp of “reasonable persona” development that seems to recognize that companies have research cultures with varying appetites for qualitative versus quantitative methods.

Company marketing and customer insights departments have for so long relied almost exclusively on quantitative for critical business decisions, while qualitative research has been regarded dismissively as something that “marketing and advertising does with focus groups”. Within companies this has caused an enculturation of a limited world view of qualitative research.

Now that that the lines between mass-media marketing/advertising and product development are blurring, there is a wonderful opportunity for more holistic views of customers, the messaging to which they will be receptive, and what they will actually interact with. This is a very exciting time to be in research, design, strategy, and brand planning.

I interact with (or see the back side) of a lot of companies. Sadly, those who even have dedicated resources aligned to the web site are far fewer than those who do (what they ‘say’ and what they ‘do’ are far different behind the scenes).

I am new to IA. Listening to experts talking about personas makes me think of one thing. Why can’t some forms of ‘psychological tests’ be designed for application during users’ research? To build good personas, we need to collect quantitative and qualitative information. As concerning qualitative analysis (or interviews), what you want is the user to tell his or her frustration about using the website, reasons for that frustration, etc. In most of the cases, it will be embarrassing for the person to let you know his or her own ignorance about use of computers and websites.

In this case, I don’t see how methods such as surveys will help to get at the bottom of this problem. Probably, observing users using the computer may be a useful way, but then, you can only see what he or she is doing; but the mental process of this information search is hard to guess. Of course, observation allows picking up a few clues about usability problems, but still may not yield much in terms of what goes on in the mind of the users.

Someone has to come up with a “psychological test applied to usability’, identify a set of smart questions that could tease out subconscious answers, discriminate a lie from the truth and retrieve what really goes through the user’s mind. Such a test may yield necessary elements to build more realistic personas.

In my view, personas are close to “identikit pictures”. Police officers always build them so as to put a face on their offender. It is amazing that with few details, the officers are able to make a drawing close to the real face. Identikit pictures should held us to understand how to make better personas.

Boke Landu Nkoy

I am studying Information Architecture at the University of Canberra. I am finding all those subjects fascinating. I came from a different background; a bit of statistics and economics. So, I enjoy all those writings; unfortunately, I start to realize that IA, personas, controlled vocabularies, diagrams, content analysis, taxonomy, labeling, etc seem to be new fields of studies where virtually we are still trying to invent the wheel.

Boke, I highly recommend reading Mulder’s book if you’re interested in persona development or learning about how user research is used to inform IA. It is vastly different from police interrogations and psychology that attempts to uncover subjects’ deception. It isn’t a threatening environment–or at least shouldn’t ever be–so the cumpulsion to lie isn’t really an issue. While cognitive psychology does play a role, these methods draw more heavily from cultural anthroplogy and related field studies.

If user or persona research is designed well, research participants do not intentionally mislead the researchers. That said, however, what people say they do versus what they actually do can be very different. This is why a balance between quantitative and qualitative is critically important. ‘Psychological tests’ don’t really gain the researcher anything. The purpose of user-centered design is to inform IAs and interaction designers so they can build systems and interfaces that aid the user in their pursuits. It is a group of methods that actively and iteratively involve users in the design process.

If you’re new to information architecture, you’ll probably also hear people frequently refer to the “Polar Bear Book”, which is Information Architecture for the World Wide Web by Rosenfeld and Morville. This is a critical, if long, primer for the IA professional–read it!

In response to Boke’s comment re a “set of smart questions,” a methodology has been developed that does delve deeper and draw out more meaningful and pertinent information. It’s now known as Cognitive Edge, and was pioneered by Dave Snowden (formerly of IBM’s Cynefin Centre, or is that of IBM’s former Cynefin Centre). I was so impressed with the methodology that I got my accreditation this spring.

At any rate, here’s an example of the qualitative difference of data that can be gathered. A survey asks on a scale of 1 to X, say 1 to 7 for purposes of this exercie, about a matter, with the best rating being the higher number. How people interpret the question will affect how they average the rating. For example, “how do you rate the administrative function” could rate 4 if it’s average, or a person could rate it 4 if they kind of like 3 things but detest 1 thing. And the more surveys you gather, the less meaningful the data becomes. However, if you gather anecdotes (the quality of the prompting questions are critical), and then attach have the respondents rank the anecdotes (in effect, using metadata) on a bell curve where answers in the mid-range are acceptable, and the “trouble signal detection” lies in the outer ranges, then it becomes more obvious where the clusters are. First, you gather information about things that may never come up on a survey; second, because the respondents do the ranking, the attribution ranking is accurate; and third, the good/bad dichotomy is replaced by a hypo-state/normal-state/hyper-state paradigm that is more tolerant of what is “normal.”