It was a tense meeting. Forty-eight hours before launch and a key multimedia effect was still not ready. The developers were trying to catch up on a long punch list of bugs; the designers wanted last-minute changes to things that were already on the “done” list. No one knew what to do. But there was a deadline, and the reviewers were coming. As a team, we walked through the schedule again and again until we had a plan. The next day, the video was edited, the shop finished the screens, and the production crew walked through the critical paths. Two nights later, the cannon fired, the song began, the screen dropped into place, the film played just as we’d envisioned it, and the cast members of “A Man’s A Man” took their bows before an appreciative live audience. Another show had opened.

|

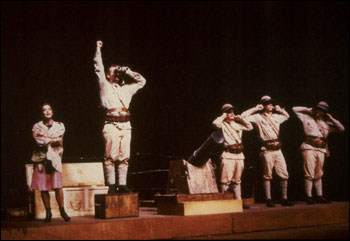

| “A Man’s A Man” by Bertold Brecht Hyde Park Festival Theater, 1986. Directed by Tim Mayer. Lighting by Whitney Quesenbery. With Bill Murray, Stockard Channing, Gerrit Graham, Mark Metcalf, Brian Doyle-Murray, Bob Halley, Jr. |

I became a lighting designer because I was in love with live theater, where lighting only exists in real time as part of the performance. Certainly, it has a utilitarian role: to put enough light on the stage so that the audience can see the actors. But the lighting also helps shape the performance by providing the color and overtones that add meaning and layers and depth. The same mix of art and technology, craft and discipline exists in user interface design.

Fast forward a few years, and it’s another tense meeting. Our demo was part of a presentation to the board of directors who were voting on whether to fund a new multimedia news service, but the video encoding was taking longer than we expected, and we weren’t sure if the bookmark feature would be intuitive enough. More late nights and it all came together. Another project launched.

As different as my two careers may seem from the outside, I never thought they were so different. Switching from theater design to interface design, I traded a forty-foot wide proscenium for one that was just seventeen inches across, and the big gestures of the stage for the more subtle movement of a hand on a mouse.

Are we all on the same team?

One thing that software and theater have in common is how many different skills are required. There are individual performance artists who pretty much do it all — write, direct, design, perform — creating perfect gems of performances, just like there are personal websites conceived and created by a single person. But most productions are the results of work by dozens of different people. At the center is the director, surrounded by the production team: designers, choreographer, and musical directors. Each of them has a team of people to create the design. It takes a lot of collaboration to keep everyone’s work in sync. We used to ask, “Are we all designing the same show?”

Sometimes we weren’t. When there was no shared vision–no overall design concept — I would end up in a situation like trying to light a musical comedy with a brown set and dark, brown wool costumes. Brown wool soaks up all the light and dulls the production’s sparkle. The lights may be bright and the actors perky, but the whole effect doesn’t hang together, and the audience can always tell.

But when all the elements work together, the effect is profound.

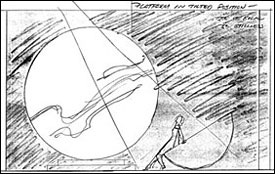

On the opening night of a new opera that I lit, the curtain opened on a scene that looked just like the pencil sketches from our design brainstorming sessions. Everything had come together to bring that vision to life. It wasn’t just that the stage looked like the picture. A performer told me that it felt like the only place where that opera could possibly take place, that it just “felt right” to be singing that story on that stage.

|

|

|

| Original sketches and the actual scene for “Tomorrow and Tomorrow” by Timothy Sullivan Center for Contemporary Opera, 1987. This one-act opera is an interior monologue, recounting an unhappy and lonely life. Directed by Stephen Jarrett. Scenery by Robert Edmonds. Lighting by Whitney Quesenbery. With Suzan Hanson. | ||

A theatrical production includes several teams of people. Just in the physical production alone, there are scenery, lighting, costume and sound designers, supported by carpenters, electricians, drapers and a whole raft of craft shops to build and install the sets, props, effects and lights. As many as 50 craftspeople may be working in a theater just a day before opening night. That’s a lot of people, especially for the speed with which shows are produced. The collaboration works only because the roles and responsibilities are well defined and respected.

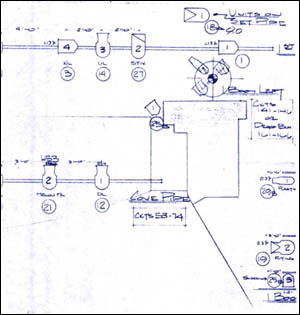

Despite all my years away from theater, I could still draw a competent light plot. It would not reflect all the new equipment and the design would probably look out of style, but an electrician would still understand it. The design artifacts communicate not only within a single craft, but between disciplines, and they are the language of the collaboration.

We are just beginning to understand all of the roles in designing the user experience. From the brand design that expresses the promise to the user interface that communicates it to the code that supports the functionality and interaction, all of the designers need to be speaking with one voice and a language that lets them work together.

|

|

| There is a standard set of paper work, or design artifacts, that includes the light plot, hookup, cue sheets and, to help the designer, a magic sheet. | |

If you can’t find it… it might as well not be there.

A lot of the work of putting on a play is simple craft. In lighting design, that means putting all the pieces together in a technically competent way so circuits don’t blow, lights don’t fall, and fire laws are followed. You need to have the lights placed so the entire stage can be lit, effects can be created… and the budget met. Finally, after all the planning and preparation, you go into the theater and create the cues — the looks, timing, and changes in the lighting — and coordinate them with the work of the actors and the other designers. And here, you get a few moments for inspiration and art.

When those moments come, it’s easy to forget that it’s not all about the lighting. The audience comes to see the play, and your work is just one part of the whole thing. Pursue gorgeous chiaroscuro at the expense of illumination and you get lighting that creates an effect of dark shapes. “The ones at the top that don’t move… those are the scenery. The shapes moving at the bottom… those are the actors.” When that happens, the designer has forgotten that, as important as the design is, the audience doesn’t come for the lighting or leave “singing the scenery.” Worse, instead of being wowed, they may just be baffled. It’s hard to hear when you can’t see the actors’ faces, and the brilliant nuances of the design are probably lost on an audience that came for the play.

I used to wonder why so many experienced professionals couldn’t get it right on the first try. Why were scripts that seemed so obviously bad on opening night ever produced? Wasn’t the very heart of the profession being able to visualize the results in advance? But what you can’t see in advance is how it will all fit together. You are supposed to be designing not only the same show, but the one the audience wants to see. That’s why those preview performances are so important: they give the production a chance to add the audience to the collaboration and to knit all the elements together more tightly.

Usability testing… coming to a theater near you

When you’ve worked on a show for several weeks, it’s hard to remember what it’s like to walk in the door and spend two hours seeing the performance unfold. You know all the nuances and characters and turns of plot. But what’s the experience like for an average audience? In software design, the solution to this dilemma is usability testing. In theater, it’s previews. A production used to have out-of-town tryouts. A show would play in smaller cities, testing the production in front of live (and paying) audiences until it was ready for Broadway. Other plays are developed in workshop or regional theater productions. Either way, it gives everyone a chance to see the play “on its feet” and make changes before they face the New York critics. It’s a nightly, elaborate usability test, as audience reaction is scrutinized and the production adjusted (whether minor changes or massive rewrites) until it all works for the audience.

One year, the Big Apple Circus included a famous clown, a top star of the one-ring European circus, with an act that was completely different from the red-nose physical humor of American clowns. His first night, he bombed. The kids just stared at him with no laughs and hardly even a giggle. We all waited for the tantrum, for the star to blame the audience. Instead, the next morning, while we were working on the lights, he brought his trunk into the ring and quietly rehearsed. That night, he got a few laughs, and over the next days he continued to work, changing some bits, dropping some, adding new ones. By the end of the week, he was getting the big laughs and the applause. He didn’t do it by abandoning his style of clowning, but by listening carefully to the audience and learning how to speak to them.

A play is different to everyone who sees it, just like an interface is different to every user. The interaction between the performers and the audience is part of the magic. Software is like that to me: a dance between person and machine, different in small, subtle ways every time, something that comes to life only in the user experience. It’s not surprising that when I was seduced away from theater by a small beige box, it was to design the user interface. The interface is live in the interaction, taking place in real time.

| For more information

Want to know more about theatrical design? The two books I have read and re-read are:

Each was a pioneer, changing our vision of how theater is made. |

| Whitney Quesenbery designs user interfaces for Cognetics Corporation, a design and usability company dedicated to creating excellent user experiences. She is the manager of the STC Usability SIG and a member of the board of directors for UPA. |

![]()