Gone, thankfully, are the days when the user experience and the user interface were an afterthought in the website design process, to be added on when programming was nearing completion. As our profession has increasingly gained importance, it also become increasingly specialized: information design, user experience design, interaction design, user research, persona development, ethnographic user research, usability testing—the list goes on and on. Increased specialization, however, doesn’t always translate to increased user satisfaction.

My company conducted a best practice study to examine the development practices of in-house teams designing web applications—across multiple industries, in companies large and small. Some teams were large and highly specialized, while others were small and required a single team member to perform multiple roles. We identified and validated best practices by measuring user satisfaction levels for the applications each team had designed; the higher the user satisfaction scores for the application, the more value we attributed to the practices of the team that designed it.

We did not find any correlation with user satisfaction and those teams with the most specialized team members, one way or the other: some teams with the most specialization did well, and some teams did poorly. What we did consistently observe among teams that had high user satisfaction scores, was one characteristic that stood out above all the others—what we began to call shared, holistic understanding. Those teams that achieved the highest degree of shared, holistic understanding consistently designed the best web applications. The more each team member understood the business goals, the user needs, and the capabilities and limitations of the IT environment—a holistic view—the more successful the project. In contrast, the more each team member was “siloed” into knowing just their piece of the whole, the less successful the project.

All of the members of the best teams could tell us, with relative ease, the top five business goals of their application, the top five user types the application was to serve, and the top five platform capabilities and limitations they had to work within. And, when questioned more deeply, each team member revealed an appreciation and understanding of the challenges and goals of their teammates almost as well as their own.

The members of the teams that performed less well not only tended not to understand the application as a whole, they saw no need to understand it as a whole: programmers did not care to know about users, user researchers did not care to know about programming limitations, and stakeholders were uninvolved and were considered “clueless” by the rest of the development team. These are blunt assessments of unfortunate team member attitudes, but we were surprised how often we found them to be present.

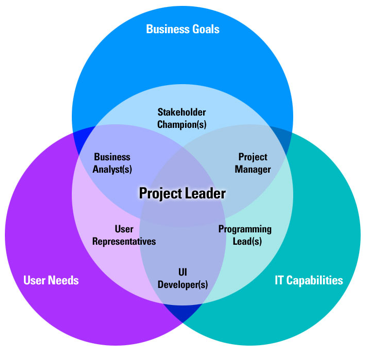

We also observed that the best teams fell into similar organizational patterns—even though there was a blizzard of differing titles—in order to explore and understand the information derived from business, users and IT. We summarized the organization pattern in the diagram below. We chose generic/descriptive titles to simplify the picture of what we observed. In many cases there were several people composing a small team such as the “UI Developer(s)” or the “User Representative(s)” often with differing titles. Also fairly common were very small teams where the same person performed multiple roles.

Fig. 1 — Teams tend to organize in similar patterns in response to the information domains they need to explore and understand

Even this simplified view of the development team reveals the inherent complexity of the development process. The best team leaders managed to not only encourage and manage the flow of good information from each information domain, but they also facilitated thorough communication of quality information across all the team members regardless of their domain. Here’s how they did it.

Five Key Ways to Promote Shared, Holistic Understanding

1. All team members—all—conduct at least some user research

Jared Spool once wrote that having someone conduct user research for you is like having someone take a vacation for you—it doesn’t have the desired effect! On the best teams, everyone, from programmers to stakeholders, participate to some degree in user research. A specialist on the team often organizes and schedules the process, provides scenario scripts or other aids to the process, but everyone on the team participates in the research process and thus has direct contact with actual users. There is no substitute for direct contact with users. Interviewing living breathing users, ideally in their own home or work place, makes a deeper impression than any amount of documentation can duplicate.

2. Team members participate in work and task flow workshops

Designing applications to support the preferred work and task flow of the users—providing the right information, in the right features, at the right time—is one of the hallmarks of applications that get high user satisfaction scores. The best teams devote enough whiteboard-style collaborative workshop time to explore work and task flow (including in the sessions actual users when possible), until all team members truly understand all the steps, loops and potential failure paths of their users.

3. Team members share and discuss information as a team

A simple practice, but one which is often overlooked, is taking the time to share and discuss findings and decisions with the entire team. Too often teams communicate information of significant importance to the project through documentation alone or through hurried summaries. Even if it is not possible for the team to participate in all user research or in mapping out all work and task flow on a whiteboard together, at a minimum, the team should go through the results of these processes in sufficient detail and with sufficient time to discuss and understand what has been learned.

Direct participation is the most effective way to learn and understand. Full and relaxed discussion with team members is the second best. Reading documentation only is the least effective way for team members to retain and understand project information.

4. Team members prioritize information as a team

Not only is it important that all team members be familiar with information from all three domains (business goals, user needs, and IT capabilities), but it is especially significant that they understand the relative importance of the information—its priority.

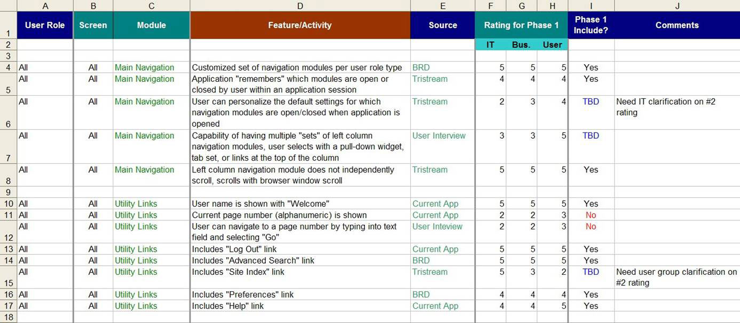

My company developed what we call a “Features and Activity Matrix”, based on our own experience designing applications, and from the practices we observed in our study. The features and activity matrix accomplishes two things:

- It forces teams to translate business goals, user input and IT capabilities into specific proposed features or activities that a user would actually see and use at the interface level. We have found that if an identified user need (for example, the need to know currency conversion values) isn’t proposed as a specific feature (say, a pop-up javascript-enabled converter, tied to a 3rd party database) then a potentially important user need either gets lost, or is too vague to design into the application.

- The features and activities matrix allows team members to prioritize the proposed features and activities from the perspective of their own domain through a process of numeric ranking. Business ranks according to the importance to the business, IT ranks according to “doability” (measuring budget, resources and schedule against each proposed feature and activity), and the user representatives rank according to their assessment of what will make users most satisfied.

The numeric ranking for each feature or activity, from each domain, is then averaged to arrive at a consensus prioritization of every feature and activity proposed for the application. If, as is usually the case, the team is already aware that they cannot do everything that has been requested or proposed, this is a very effective way to determine which features and activities are not going to make the cut and which ones have the highest importance.

Fig.2 — Features and Activities Matrix. Note that we used a ranking scale of 1-5, 5 being the most important.

5. Team members design together in collaborative workshops

Once information from all three domains is gathered, analyzed, shared and prioritized, the remaining—and most powerful—practice to promote a shared, holistic understanding is to conduct wireframe-level, whiteboard-style, collaborative design sessions. Your session participants should include a solid representation of users, business and IT but not exceed roughly 12 people. In these workshops teams can work out together the basic layout, features and activities for most of the core screens needed for a project. These sessions can, and should, require multiple days. We have found that between 10 and 20 core screens can be considered, discussed, iterated and designed in 4-5 days of workshops.

Make sure everyone is fully engaged: business cannot be half committed, and IT cannot say that they will determine later if the screen can be built. All team members should be prepared to make real-time decisions in the collaborative design session. Inevitably there will be a few things that simply cannot be decided during the session, but the greater the shared, holistic understanding that already exists, the fewer things that will require processing and final decisions outside the session.

A well prepared collaborative design session both promotes and leverages the team’s shared, holistic understanding of the project. Even though they are time consuming, collaborative workshops eventually save time because the team ends up needing less iterations to refine and finish the design. Collaborative workshops also insure higher quality; there are fewer missteps and errors down the line because of the shared understanding of the design. Finally, collaborative workshops create great buy-in from business and IT. It is far less likely that some—or all—of the project will undergo unexpected or last minute changes if the goals and priority of features is clearly established during the design process.

Whatever the size and structure of your team, and no matter how many or how few specialists it has, your outcomes will be better if everyone shares a holistic understanding of the work at hand. Taking the extra time as a team to develop a shared holistic understanding pays off in greater efficiency in the long run—and most importantly—in greater user satisfaction and overall success!

Nice article, Joseph. I agree with you that shared understanding of both the product and the roles of other team members is critical. I’ve also used the Features Matrix approach on projects before with good success.

One question that came to mind as I was reading is how to factor in the inherent complexity of the domain in which the product sits. Obviously, one of the reasons why team members might avoid learning about other people’s work is if that work is ridiculously difficult to understand. I’ve experienced projects where, for example, the underlying technology was so complex that even within the IT segment, few developers understood what their development colleagues were doing. I’m not sure they all understood their OWN work. =) In situations like this, the lack of holistic awareness is clearly a big problem, but I suspect that creating a holistic awareness would involve so much effort that it would be counter-productive. For practical reasons, there may be a point when the complexity of the domain requires a team to shift from holistic awareness to trust in one’s teammates in order to be successful.

From numbers 1 to 4, the article is quite useful. I’ve identified especially with #1 and always look for ways to get our UX Corporate (multidisciplinary) group to be involved in research.

However, for #5, I must disagree. Designing in a group I found to be very counter productive. There’s too many ideas floating around even if there’s less than a dozen people. Focus also isn’t achieved because there’s no real structure and there’s too many people (from too many disciplines) wanting to design but don’t have the skills to design. Instead, I suggest leaving the designing to the designer. Do it in iterations where a group may be able to review. Or better yet, have a design tested and have the group review the test results. And in order to come up with an initial mockup, have the designer listen to a requirements discussion or at least review the requirements before creating it.

I found that as a designer, it’s better to not design until I pull out key phrases and words to form what needs to be achieved. Only then can you start designing anything.

Terry,

Sounds like you’ve been there :).

In the main I agree with your comment. Even in less complex environments than the one you describe I don’t think it is possible for all team members to *fully* understand the complexities of the IT environment — and harder still in the scenario you describe. But at a minimum I think it is still possible, and very important, that all team members are given enough information from the programmers/programming lead that they know what can and cannot be done at the interface and interaction level (i.e. drag and drop?, fixed javascript library?, custom javascript effects, .net extensions?) and any significant data limitations, in order for the user experience to be designed in such a way that it can be built as designed.

There are few things more damaging to the final outcome of a project than to have the design spec come unraveled when it gets to the development stage. When that happens, less well thought out (and almost always less user centered) solutions are substituted for the ones in the original design, and due to press of time, these solutions cannot be iterated again with the full team.

Better by far to be able to perform the user experience design process with a shared holistic awareness of what *can* be done — even if many team members can’t fully appreciate the “why” the limitations.

Best regards,

Joseph

Benjamin,

I can sympathize with your description of a group design process. They can go way off purpose. We call them “goat rodeos” when that happens. However, a well planned collaborative session, sometimes lasting several days, can move through issues, problems and iterations very rapidly, which would otherwise take weeks (or not be done at all).

The secret we have found is preparation. We are very careful to get real decison makers in the room from all three domains. We make sure that business goals are clear before we start. We also have some ideas already “in our pockets” that we can begin sketching on the white board to get things going. And we make sure that the scope of the session is clearly delineated — a particualr work flow is usually how we focus it.

It is also very important that whoever facilitates the sessions can bring things back to focus when they (inevitably) go off on tangents, and knows when to “table” certain important discussions for future resolution.

Don’t give up on collaborative sessions :). Done right they can give magical results!

Best regards,

Joseph

Joseph,

“Goat rodeos”, huh? How classic!

I think the big challenge we have is thinking in terms of work flow. Unfortunately, we don’t operate so much that way – which is why we’re on the track to develop Personas to get us on track. (We never used to really think about the user either.)

I’m glad you gave tips on how to get people to collaborate in such design sessions. So far, I can say with confidence that we’ve only completed ONE design session successfully. To get everyone focused is a huge challenge too.

Jamie,

Thanks for describing the jigsaw approach. I can see us using it in future.

Your post also gives me the opportunity to emphasize (and empathize with) the point you make about the additional challenges of geographically dispersed teams. In our study we found that geographically dispersed teams, in order to be successful, needed to make extra effort to acheive a shared holistic awareness of their project. Teams that enjoy close proximity can develop a certain amount of shared awareness simply because they have conversations in the hall, or can easily sit down for 10 minutes to go over a specific point, but this natural communication process is missing when teams are separated.

Geographically dispersed teams are especially helped by the intensive focus of shared collaborative workshops. Budget constraints and schedules militate against workshops, and of course teams need to work within the realities imposed on them by circumstances. But if at all possible, I highly recommend having at least one multi-day collaborative session as described in my article. It does wonders to bring things into focus.

Best regards,

Joseph

Hi, Joseph:

I really wish more companies GOT this concept, because it can easily be applied to so many more disciplines than Web Design. With downsizing running rampant (and the resulting job paranoia predictably going unchecked), I am seeing more and more the application of what I call the “Three Lock Box” approach to nearly everything. Every member of the diminishing team owns/excels in one aspect of a given project, but none understands the overall project goal. Most times, we cannot even come to agreement on the most effective approach. The catch-phrase “you OWN IT” is still slung around like beans and hash by middle management, but how can “ownership” even be conceived of when one cannot contribute anything to the project substantively while the other team members are out skiing, taking a mental health day, or home tending to a sick kid?

I think I’ll pass a link to this article on to my boss tomorrow.

Best regards,

— Steve Pomeroy

Manchester, NH

Great article Joseph.

I really like how you discussed the disconnect between researchers, designers and stakeholders and how that relates to overall user satisfaction. As a UX researcher, I notice that the breakdown between team members always seems to come back to communication and planning. Once the project begins and the workload increases, the communication seems to decay and the planning starts to fall behind. I’ve found that the more time you spend up front building a plan for success and outlining the project goals with the entire team present (researchers, designers, stakeholders, etc.) the more likely the project will proceed smoothly and end with positive marks.

Hello Joseph,

I am inspired by this post and actually made a another one to help understand the holistic approach to Service Design… But yet have some confusion over what I can use to replace the right corner where the ‘IT Capabilities’ was in your graph, since the technology Service Designer use varies largely according in individual projects… My assumption is that they use techniques such as observation and visual communication to stimulate conversations among stakeholders… well… wonder if you have any oppinon or suggestions?

Comments welcomed in my blog post on the topic as well 🙂

http://designgeneralist.blogspot.com/2009/03/holistic-view-for-service-design-team.html

Thanks!

Qin

Steven,

I feel your pain :). As an outside consultancy, my company (Tristream) is often brought in when a high-value or mission-critical project is showing distinct signs of upcoming failure. The project is nearly always heading for failure because of really basic reasons — poor communication, lack of clarity in the business goals, missing expertise, and no real project leadership to facilitate the holistic understanding of the project across all the affected domains. Fixing these problems doesn’t always require adding significantly more resources, pushing out the deadlines, or anything that has a high negative impact on the company. The fixes are usually just a matter of focusing the project.

Good luck,

Joseph

Bryan,

Thanks for your comment. An ounce of planning is always worth a pound of work. But these days, with the ever increasing pressures to produce products and solutions faster, there is less ansd less time allowed for planning. Agile programming is just an example. The challenge these days is to make planning an ongoing process, to fit in with faster release cycles, and shared holistic awareness across all domains becomes even more important when decisions and planning need to come at a faster rate. The shorter the cycle time it takes your team to synch up on new goals and apply the creativity needed to support them the better.

Best regards,

Joseph

Qin Han,

I am not as aware of the field of service design as I am of experience and interactive design, but it seems to me that the equivalent domain to IT capabilities in the world of service design is whatever physical otr electronic aids the service providers need in order to provide their service. This could be telephony, real-time knowledgebase provision, check out systems, hand-held wireless tablets, on screen or printed script reminders, etc.

I hope that is helpful.

Best regards,

Joseph

Hey Joseph,

I think the planning process definitely needs some rethinking; it should be more efficient with the ability to provide the same quality plans in less time. Maybe some specialized planning tools or methods should be designed to restructure the planning process to achieve this goal. I think more effective communication among team members during the planning process (and beyond) is a good start. The more efficiently concepts can be communicated between team members, the less time it will take to plan and execute projects.

Thoughts?

Thanks

Bryan

I’ve come to appreciate the value of point 5 (collaborative design) while also understanding where Benjamin Ho’s initial skepticism is coming from. No, you don’t want design by committee – it can lead to a lowest common denominator solution. But you do want buy-in and ideas from all the sectors in Joseph’s Venn diagram. In the evolution from our early attempts to implement UCD to the present, we made lots of naive but valuable mistakes. Like going out to customers with designs they loved, only to find on showing the specs to the developers that a central premise was not feasible given the technology platform. Our conceit that interaction designers know UI design best was quickly punctured as we got some great ideas from developers. So now we’ve rechristened UCD as “user-centred development” in an attempt to institutionalize it and move it beyond a design “silo”. Our designs evolve based on usability expertise guided by early contributions from the overall project team and frequent user checkpoints. And we find as a result that we’re designing with much more confidence.

(Joseph, a quick question: in Figure 2, what would make Welcome User Name a 5 but current page number a 2 from the IT perspective? They both seem relatively trivial.)

Collaborative workshops definitely produce higher quality. What’s interesting is when those collaborators are teams who who are high on data type research and learning what UE research means to their product. It’s very exciting to train teams outside of CA in UE methodologies and watch them rise to the occasion with enthusiasm.

Thank you for this GREAT article!