Despite the proliferation of books in the years after Gutenberg, three hundred years later books still remained prohibitively expensive for most Europeans. By the mid-eighteenth century, a typical educated household might own at most a single book (often a popular devotional text like the Book of Hours). Only scholars, clergymen and wealthy merchants could afford to own more than a few volumes. There was no such thing as a public library. Still, writers were producing new books in ever-growing numbers, and readers found it increasingly challenging – and often financially implausible – to stay abreast of new scholarship.

At the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment, a handful of philosophers, inspired by Francis Bacon’s quest for a unifying framework of human knowledge[1], started to envision a new kind of book that would synthesize the world’s (or at least Europe’s) intellectual output into a single, accessible work: the encyclopedia. Although encyclopedias had been around in one form or another since antiquity (originating independently in both ancient Greece and China), it was only in the eighteenth century that the general-purpose encyclopedia began to assume its modern form. In 1728, Ephraim Chambers published his Cyclopedia, a compendium of information about the arts and sciences that gained an enthusiastic following among the English literati. The book eventually caught the eye of a Parisian bookseller named André Le Breton, who decided to underwrite a French translation.

Enter Denis Diderot. A prominent but financially struggling writer and philosopher, Diderot occasionally supplemented his income by translating English works into French. When Breton approached him about the Cyclopedia, he readily accepted the commission. Soon after embarking on the translation, however, he found himself entranced by the project. He soon persuaded Breton to support him in creating more than a simple translation. He wanted to turn the work into something bigger. Much bigger. He wanted to create a “universal” encyclopedia.

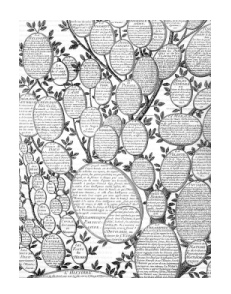

Adopting Bacon’s classification as his intellectual foundation, Diderot began the monumental undertaking that would eventually become the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers (“Encyclopedia or Dictionary of the Sciences, the Arts, and the Professions”), published in a succession of volumes from 1751 to 1772. A massive collection of 72,000 articles written by 160 eminent contributors (including notables like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Buffon), Diderot turned the encyclopedia into a compendium of knowledge vaster than anything that had ever been published before.

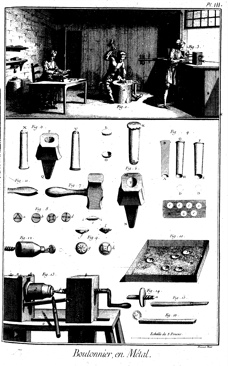

Diderot did more than just survey the universe of printed books. He took the unprecedented step of expanding the work to include “folk” knowledge gathered from (mostly illiterate) tradespeople. The encyclopedia devoted an enormous portion of its pages to operational knowledge about everyday topics like cloth dying, metalwork, and glassware, with entries accompanied by detailed illustrations explaining the intricacies of the trades. Traditionally, this kind of knowledge had passed through word of mouth from master to apprentice among the well-established trade guilds. Since most of the practitioners remained illiterate, almost none of what they knew had ever been written down – and even if it had, it would have held little interest for the powdered-wig habitués of Parisian literary salons. Diderot’s encyclopedia elevated this kind of craft knowledge, giving it equal billing with the traditional domains of literate scholarship.

While publishing this kind of “how-to” information may strike most of us today as an unremarkable act, in eighteenth-century France the decision marked a blunt political statement. By granting craft knowledge a status equivalent to the aristocratic concerns of statecraft, scholarship, and religion – Diderot effectively challenged the legitimacy of the aristocracy. It was an epistemological coup d’ étate.

Diderot’s editorial populism also found expression in passages like this one: “The good of the people must be the great purpose of government. By the laws of nature and of reason, the governors are invested with power to that end. And the greatest good of the people is liberty.” To the royal and papal authorities of eighteenth century France, these were not particularly welcome sentiments. Pope Clement XIII castigated Diderot and his work (in part because Diderot had chosen to classify religion as a branch of philosophy). King George III of England and Louis XV of France also condemned it. His publisher was briefly jailed. In 1759 the French government ordered Diderot to cease publication, seizing 6,000 volumes, which they deposited (appropriately enough) inside the Bastille. But it was too late.

By the time the authorities came after Diderot’s work, the encyclopedia had already found an enthusiastic audience. By 1757 it had attracted 4000 dedicated subscribers (no small feat in pre-industrial France). Despite the official ban, Diderot and his colleagues continued to write and publish the encyclopedia in secret, and the book began to circulate widely among an increasingly restive French populace.

Diderot died 10 years before the revolution of 1789, but his credentials as an Enlightenment encyclopedist would serve his family well in the bloody aftermath. When his son-in-law was imprisoned during the revolution and branded an aristocrat, Diderot’s daughter pleaded with the revolutionary committee, citing her father’s populist literary pedigree. On learning of the prisoner’s connection to the great encyclopedist, the committee immediately set him free.

What can we learn from Diderot’s legacy today? His encyclopedia provides an object lesson in the power of new forms of information technology to disrupt established institutional hierarchies. In synthesizing information that had previously been dispersed in local oral traditions and trade networks, Diderot created a radically new model for gathering and distributing information that challenged old aristocratic assumptions about the boundaries of scholarship – and in so doing, helped pave the way for a revolution.

Today, we are witnessing the reemergence of the encyclopedia as a force for radical epistemology. In recent years, Wikipedia’s swift rise to cultural prominence seems to echo Diderot’s centuries-old encyclopedic revolution. With more than three million entries in more than 100 languages, Wikipedia already ranks as by far the largest (and most popular) encyclopedia ever created. And once again, questions of authority and control are swirling. Critics argue that Wikipedia’s lack of quality controls leaves it vulnerable to bias and manipulation, while its defenders insist that openness and transparency ensure fairness and ultimately will allow the system to regulate itself. Just as in Diderot’s time, a deeper tension seems to be emerging between the forces of top-down authority (manifesting as journalists, publishers and academic scholars) and the bottom-up, quasi-anarchist ethos of the Web. And while no one has yet tried to lock Wikipedia up in the Bastille, literary worthies and assorted op-ed writers have condemned the work in sometimes vicious terms, while the prophets of techno-populism celebrate its arrival with an enthusiasm often bordering on zealotry. Once again, the encyclopedia may prove the most revolutionary “book” of all.

About the Book

“Glut: Mastering Information Through the Ages”:http://www.amazon.com/Glut-Mastering-Information-Through-Ages/dp/0309102383/boxesandarrows-20

Alex Wright

2007; Joseph Henry Press

ISBN-10: 0309102383

References

fn1. cf. Bacon’s Novum Organum of 1620

Alex – I’ll see your encyclopedia and raise you a Julia-set shaped mandala.

I just found that “groundplane -antenna” showed me #3 in google.

Why “groundplane”? Because the physics of antenna allow that system to discriminate best when working against a base reference.

What’s the antidote to “glut”? Well … how about subjective salience?

Correct me here, but “Data is information that matters”, no?

And how do dullards and pedants judge what matters to people? Poorly.

What about plods, fakes, and phoneys? Worse.

How does my cognitive schema in-form the encyclopedia I’m experiencing via the web? Likely, not at all, except as yet another user case that ends in my being just a bit more dumbed down.

Discourse. Discussion as though persons matter.

Or, from another direction (“mandala theory” always in mind): _glasperlenspiel_.

The all inclusive nature of “encyclopedia” … that, surely, is abused, debased, and demeaned when thought of as 2-dimensional. So how many, then?

Back when SGI was a player I toyed with 3. *shrug* Fun … tedious … futile.

Feed-back/feed-forward … re-entrant … manifold. DITA is kludge, fit only for computing machines, not nearly up to the task of making semantic web worthy of human consciousness.

But call me Cassandra: I’m bound not to have any credibility at all. Paradigmatically disruptive, ehh whot?

*grin*

–bentrem